Media International Exchange 2017.12.14

China Boom Subsiding in Europe and the U.S., but Coming Back in Japan-Gap Produced by Differences in Marketing Abilities and Structural Change of Chinese Markets-

When I visited Washington D.C. in September last year, I heard similar stories from several of my friends known as China watchers that U.S. companies' views on Chinese markets had recently been growing more negative (cautious) than ever before.

By contrast, in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou where I went on a business trip in the following month, I heard that Japanese corporations which had continued to adopt a cautious stance on investment in China over the past several years gradually started to go on the offensive, seeing their Chinese business picking up.

That is to say, I found that U.S. companies' and their Japanese counterparts' attitudes towards Chinese business were moving in opposite directions, with the former growing more negative, while the latter, more positive.

I was unable to understand why there was such a difference between American and Japanese companies' attitudes.

According to my U.S. friends, such views taken by U.S. companies were originally provided by top officials of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai who visited Washington D.C. and New York in September last year to deliver lectures to them.

Directly obtaining local information in China, the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai is an organization regarded as being well-versed in the status of U.S. companies doing business in China.

It has a reputation among China experts of not being swayed by pessimistic views of China prevalent in the U.S. stemming from growing anti-Chinese sentiment across the country, but seeing things from an independent perspective. Thus, comments given by top officials from such an organization received all the more publicity among a lot of China watchers in the U.S., and my friends conveyed them to me.

Being asked about why U.S. firms began holding such views, my American friends pointed out the following three problems as the reasons for that:

They were: 1) infringement of intellectual property rights; 2) damage to business caused by the Chinese government's sudden policy change; and 3) difficulty in collecting accounts receivable money.

The moment they were given, I felt that there was something strange, because all of them were the very problems that Japanese corporations had continued to point out since around 2010 when they started to focus their efforts on making inroads into Chinese domestic markets.

I could not believe that views on Chinese markets suddenly changed last autumn due to these reasons.

Considering that there must have been real reasons behind the change, I went on to convey the above story to many people, including Japanese businesspeople, government officials and scholars stationed in China, and asked them for the reasons. However, none of them could give me convincing reasons.

Circumstances surrounding European and U.S. companies' Chinese business

In late September this year, after a year had passed since I heard the above story, I made a business trip to the U.S. and told the story to a famous scholar in international politics with extensive knowledge about China.

She proposed that I should meet with a top official of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai whom she would introduce me to and ask him for the reasons, and immediately sent him an email to introduce me.

I met the top official in person during a business trip in Shanghai at the end of October, the following month. As the answer to my question, he stated as follows:

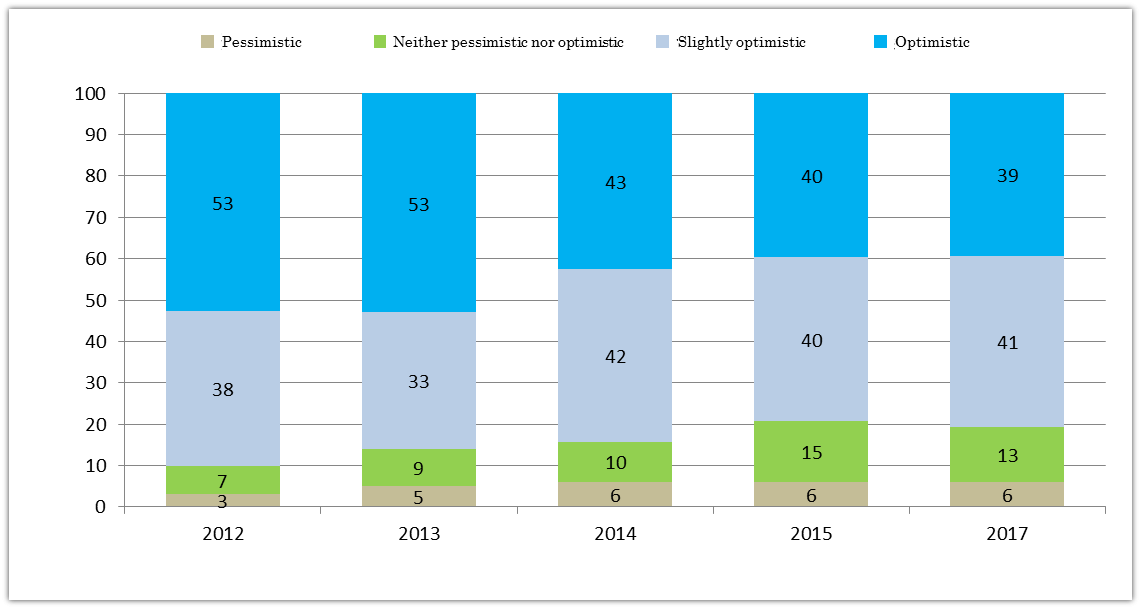

It is true that U.S. firms' views on Chinese business have been growing more negative than ever before in recent years. According to the results of questionnaire surveys of U.S. companies operating in China, the change did not occur last year but has started to be seen from 2014 onwards (See the chart below).

(Note) Based on surveys conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. There were 426 respondent companies. The 2017 survey period was from April 11 to May 7, 2017. The data are cited from the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai's China Business Report.

However, their views vary across industries. Since industries such as automotive, pharmaceutical and healthcare continue going well even now, the stance of related companies' towards Chinese business remains positive.

On the other hand, IT-related companies take a harsher view of Chinese markets. This is because Beijing's tightening of various regulations prevents American IT firms from freely doing business in the country.

Companies in the daily necessities industry, meanwhile, adopt a middle stance. Lately, manufacturing daily necessities such as shampoo of higher quality than before, local Chinese enterprises have been raising their profile in markets once dominated by U.S. corporations, thereby beginning to erode the market share of the latter.

As just described, although varying from one industry to another, the business environment in China is becoming increasingly severe for U.S. companies on the whole.

In addition, the fact that violations of intellectual property rights have not been corrected and that China's economic growth slowed last year have contributed to the shift in U.S. companies' views on Chinese markets from positive to negative.

These were the key answers provided by the top official of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai to my questions which I had sought since last year.

During the business trip, I also visited the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China to ask them about the stance of European firms towards Chinese markets. It was pointed out that they had also been enhancing a sense of caution over China over the last couple of years due to the following three reasons:

Firstly, the fact that a number of excellent European businesses are bought up by Chinese enterprises is thought to be a threat.

Secondly, in this era where, in line with the advancement of AI (artificial intelligence), big data take on the same significance in a variety of industries, equivalent to that which oil used to have, Chinese companies have a huge advantage in data collection over their competitors in other countries.

Thirdly, Chinese companies have excellent innovation abilities as shown in various fields such as smartphone, ecommerce and fintech.

It was said that although Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany maintained a close relationship with Beijing, German business communities had increased a sense of caution over Chinese enterprises and become less willing to make investment in China than they used to be.

As seen above, I was able to confirm that U.S. and European companies having a good understanding of Chinese markets were adopting increasingly negative or cautious stances towards Chinese business or enterprises, although the reasons varied from company to company.

Meanwhile, I have heard that due to increases in Chinese sales and profits in 2017 on solid domestic demand in that country, many European and U.S. firms have recently seen a brighter future for Chinese markets than in 2016 when China's economic growth slowed.

Nevertheless, European and U.S. companies on the whole appear to remain cautious about expanding their investment in China, in a reflection of the previously-mentioned views.

Japanese companies' adopting more positive approaches to Chinese business and the reasons for the attitude shift

In contrast to the change in U.S. and European companies' views on Chinese markets as explored above, Japanese corporations have put more efforts into Chinese business since the autumn of last year. This move has become more conspicuous since the beginning of this year and I was able to identify it clearly during my business trip to China from the end of October to the beginning of November.

The following developments are considered to be the major reasons for the attitude shift in Japanese companies:

Firstly, in tandem with the rapid rise of China's middle class, demand for Japanese companies' products and services has been growing significantly year by year.

Secondly, Japanese cars have been selling well in China, as their negative image, which had continued for about three years since the autumn of 2012 when the Senkaku Islands dispute occurred, has eventually disappeared over the last couple of years.

In particular, statistics on 2017 passenger car sales in China by country of origin show that sales of Japanese vehicles alone register a remarkable double-digit growth over the same period of last year, while sales of Chinese, German and U.S. cars chalk up only single-digit rate of growth and those of Korean and French cars decreased sharply.

Thirdly, with the number of Chinese tourists to Japan continuing to grow at a rapid rate, a lot of Japanese firms have become aware that the increasing demands of Chinese consumers can provide good business opportunities to them.

Fourthly, since the beginning of this year, China's macroeconomic fundamentals have remained more balanced than in the past several years and accordingly, it has become difficult for the media, which had struck a pessimistic tone on the Chinese economy, to continue expressing very pessimistic views.

Amid these developments, top executives of some Japanese firms who had taken cautious and negative approaches to expanding Chinese business over the past several years, have started since the beginning of this year to revise their views and direct executive officers stationed in China to hammer out new strategies aimed at increasing penetration into Chinese markets.

These four developments have in common that they have been brought about not by improvement of the marketing abilities of Japanese companies, but by improvement of the business environment surrounding them.

Understanding the rising purchasing power in China at an early stage, U.S. and European corporations have capitalized on their high marketing abilities to have an accurate grasp of Chinese market needs and boost sales on the back of growing demand.

By contrast, Japanese companies in general are superior in technological competencies but inferior in marketing abilities, compared to their Western counterparts. Thus, they failed to quickly grasp business opportunities in dramatically changing Chinese markets and supply products that met local needs.

This is the reason why despite the rapid expansion of Chinese markets, there are only a limited number of Japanese corporations whose Chinese sales have been robust.

On top of that, no sooner did China's middle class, the main target group of Japanese companies, start to explode in 2010 than the problem of the Senkaku Islands arose and made a majority of Japanese firms extremely conservative about expanding Chinese business.

As a result, top management of Japanese companies refrained from visiting China, accepted without questioning media reports highlighting a pessimistic outlook for the Chinese economy, did not strive to find and recognize any business opportunities in China, and became all the more incapable of understanding Chinese markets.

However, the negative effects of these factors are being gradually offset by the positive effects of the factors listed below, triggering a change in Japanese companies' business attitude for the better.

(1) The continued explosive growth of the middle class in China;

(2) The strong performance of the Chinese economy this year;

(3) The media gradually revising their excessively pessimistic view of China; and

(4) Certain improvements in the Japan-China relationship which had been at its worst.

While the marketing abilities of many Japanese firms remain poorer than those of their Western counterparts, demand for Japanese products and services has been on the rise as the middle-class population, the major target group of Japanese companies, increases in China.

Consequently, a positive opinion that "we, Japanese firms, are the most capable of providing Chinese consumers with what they will need and want going forward" has begun spreading among Japanese companies operating in China.

In these circumstances as seen above, Western companies' and their Japanese counterparts' attitudes towards Chinese business are moving in opposite directions.

I, looking ahead, cannot find any factors that may cause immediate changes in U.S. and European companies' cautious stance towards Chinese business, whereas the positive effects of the previously-mentioned factors which support the change in attitude of Japanese companies for the better are highly likely to linger for a while.

It seems, therefore, highly likely that the gap between the views of U.S. and European firms and their Japanese counterparts' views on Chinese business will remain for some time to come.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Mr. Seguchi's column published by JBpress on November 21, 2017.)