Media International Exchange 2017.07.18

China's Swelling Appetite for Japanese Quality Provides Golden Opportunity for Japanese Firms to Leap from Bottom of Smile Curve

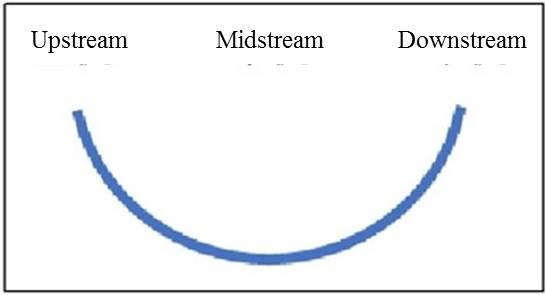

The "smile curve" is a concept designed to explain the differences in profitability for the upstream, midstream, and downstream segments of the value chain. Dr. Motoshige Itoh, professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, explains the concept. The following is a summary of his explanation.

Take the textile industry, for example. Textile material manufacturers in the upstream segment secure high profitability with the development of new high-tech fibers and carbon fibers, etc. Textile manufacturers and sewing firms in the midstream segment are generally less profitable. In the downstream segment, firms that sell products that are fine-tuned to meet consumer needs are more profitable. UNIQLO is a typical example.

In the IT industry, the upstream segment is represented by Intel and Microsoft, the midstream segment by Chinese and Taiwanese processors and assemblers, and the downstream segment by Apple.

The change in profitability along the value chain can be depicted in a curve that symbolizes a smiling mouth as shown below:

Industrial sectors in the midstream segment are subject to low profitability as they are exposed to fierce cost competition associated with growing modularity and globalization.

Given such gaps in profitability depending on the sector, the strategy to maximize profitability would be to outsource less profitable production in the middle of the value chain and focus on either end, i.e. the production of upstream materials or the sales of products that are fine-tuned to meet consumer needs.

An important factor for a company to succeed upstream is to continue to hone its skills that excel those of its rivals. In order to succeed downstream, on the other hand, a company may be required to have a balanced combination of three factors: product, business model, and brand.

That said, it is extremely difficult to thrive upstream or downstream in a fiercely competitive global market.

The question is where, along the smile curve, do Japanese firms find themselves in the global market? Most of them are situated midstream, apparently struggling to improve their profitability to little avail, while few are flourishing upstream or downstream.

Competition from tough rivals, most notably Chinese and Taiwanese firms that are unrivaled in terms of cost reduction efforts through modularization, apparently put Japanese firms in dire straits.

In fact, recently, a number of Japan's major home appliance manufacturers have suffered a bitter experience in global competition. Viewed in this light, the future looks gloomy for Japanese firms.

Seizing the moment from the bottom

There is little chance that Japanese firms will outperform Chinese and Taiwanese competitors that seek to cut costs backed by their enormous capital if they are to adopt the same business model as theirs. Fortunately, however, the typical business model adopted by Japanese firms somewhat differs from the one generally adopted by firms specializing in processing and assembly.

Chinese and Taiwanese processors and assemblers achieve low prices unattainable by others by maximizing modularity as well as economies of scale through mass production.

Japanese firms, on the other hand, excel in producing small-lot of high-quality and high-variety products. This is especially true of mid-tier enterprises as well as small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The business model that features high-variety, small-lot production does not allow for mass production that builds on an unwarranted assessment of customer needs. Rather, the model calls for accurate assessment of the needs of purchasing firms as well as timely delivery of only the required numbers of products that perfectly meet the specifications that reflect such needs.

Going all out in pursuit of such delivery may give rise to an ultimate form: the integration of the product development process of customer companies and the R&D of one's own company. Such integration involves joint research from the development stage.

This could even turn the tables, allowing midstream firms with capacity for product development and production to sway product development by upstream and downstream firms.

This is the integration of product development and production between upstream or downstream firms with midstream firms. In short, this is the moment to seize in order to leap from the bottom of the smile curve.

In fact, many Japanese mid-tier enterprises and SMEs adopt this strategy to increase the added value of their products for higher profitability. This is how many Japanese firms survive fierce global competition.

It should also be a viable strategy for Japanese firms to survive in the global market as well.

Business opportunity for Japanese firms in the Chinese domestic market

Let us turn our eyes to the Chinese domestic market. China is emerging as a market that is as important as the US market for Japanese firms. The number of Chinese tourists to Japan has surged over the past three to four years. Their binge shopping is attracting special attention.

While on a recent business trip to Osaka, I walked from Dotonbori to Shinsaibashisuji. It was a weekday evening. Even so, the streets looked as though they were a pedestrian mall on a holiday. They were flooded with Chinese tourists carrying large amounts of goods that they had seemingly bought at nearby drugstores and volume home-appliance retailers.

The conversations I heard while walking down the streets were almost all in Chinese. I was so surprised.

Until several years ago, many Chinese people could not afford to buy Japanese products even though they knew about their high quality. Now, they no longer feel that Japanese goods and services are expensive, as my experience in Dotonbori showed.

Behind this change lies a rapidly expanding middle class in China. Available demographic projections show that the total population of the regions with a per capita GDP (gross domestic product) of 10,000 dollars or more will jump from 100 million in 2010 to 800 to 900 million by 2020.

This is the data showing the upsurge in the middle class population in China. The upsurge will continue until around 2020.

This clearly offers great potential for Japanese firms to tap into the Chinese middle-class market and win far more customers of Japanese goods and services in addition to Chinese inbound tourists who come to Japan to buy Japanese products and services.

Rapidly changing needs in the Chinese market and requirements for accommodating them

The poor differ from the middle class in consumer behavior. They put top priority on meeting basic needs for food, clothing and shelter.

The middle class, on the other hand, attaches some importance to quality in buying goods or services. They are eager to differentiate themselves from others in their consumption habits. This is where needs for high-variety, small-lot production comes into play.

In short, China's swelling middle class means a rapidly growing need for small-lot production of high-quality and high-variety products in the Chinese domestic market.

While varying from region to region, market needs are changing fast in China. Once, all that was expected of goods and services was for them to meet the necessities of life: food, clothing and shelter. Now there is a rapidly growing and accelerating need for high-variety, small-lot production.

What is more, the quality standards Chinese consumers expect of goods and services are a far cry from those in the past.

The prospect is that a market that fits the characteristics of Japanese firms will swell rapidly in the near future. Or in all likelihood, it is already swelling and a few Japanese firms are seizing the moment and seeing their revenues increase sharply.

Essential requirements for accommodating such rapid changes in Chinese market needs include the localization of the development and production processes and timely decision-making by management at the headquarters to support such localization. These two requirements can only be met through the chief executive's bold judgments and decisions.

To this end, it is essential for the chief executive to visit China at least several times a year for independent thinking and timely and appropriate decision-making.

The opportune moment to leap from the bottom of the smile curve in the Chinese domestic market will soon arrive. Japanese mid-tier enterprises and SMEs will be in a better position to seize that moment.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Mr. Seguchi's column published by JBpress on May 19, 2017.)