1. Important issues Beijing faces in policy management

China’s real GDP (gross domestic production) for the July–September quarter of this year (2024) grew 4.6% from the same period a year earlier, marking two quarters in a row in which the year-on-year growth rate failed to reach the 5% mark. The rate was 4.7% for the preceding quarter.

In March, the Chinese government announced that the annual target for this year is around 5.0%. It is generally believed that a figure no less than 4.8% largely achieves that goal.

Because the figure for the period from January to September reached 4.8%, most analysts agree that the real GDP growth throughout 2024 will almost certainly reach 4.8–4.9%.

However, the prospect that the figure will fail to reach 5.0% is a source of concern for some analysts.

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party in October 2017 agreed that the most important national goal for economic policy management was to improve the quality of economic development rather than the previous goal of pursuing economic growth.

At that time, a growth rate in the 6% range was a sure bet, although the Chinese economy was in the final phase of rapid growth. This shift in government policy was largely acceptable to the Chinese public.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022, however, the rapid growth period of the Chinese economy came to an end, undermining the Chinese public’s confidence in economic prospects significantly and increasing anxiety about their future.

The Chinese economy’s potential growth rate, which signifies its current real power, is in the range of 4.0% or more but less than 4.5%, according to many analysts. It is highly likely that the rate will dip below 4% if the Chinese economy faces downward pressure due to various factors.

In fact, a comparison with the preceding quarter, rather than the same period a year earlier, shows that the real growth rate fell below 4% this year for two consecutive quarters: 2.0% for the April–June quarter and 3.6% for the July–September quarter.

In such an economic slowdown phase, it is difficult to emphasize that the most important national goal is to improve economic quality rather than to spur growth.

To be sure, the first thing to do is to alleviate the immediate anxiety of the Chinese public. This underscores the need for economic policy management that strikes a balance between these two goals: more growth and better economic quality.

2. Unprecedented continuation of economic stagnation in the July–September quarter

China’s economic policy management has to date continued to put quite an emphasis on maintaining a high growth rate even after the shift in focus to improved economic quality.

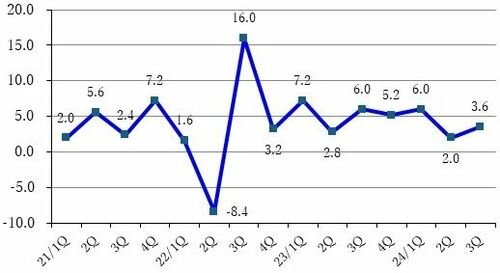

In fact, the real growth rate on a quarter-on-quarter (q/q) basis did not remain below 5% in two quarters in a row from 2021 – when stability was restored to some extent following 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc – until the April–June quarter of 2024, except in the second quarter (April–June) of 2022, when the city of Shanghai was locked down, which was an anomaly. (See the figure below.)

This was because Beijing took immediate measures to prop up the economy whenever it noticed signs of economic slowdown in order to maintain economic stability.

Changes in real economic growth rate (q/q seasonally adjusted annualized, %)

Source: CEIC

However, the recent situation suggests a slightly different trend.

This year, the q/q real growth rate plummeted from 6.0% for the January–March quarter to 2.0% for the April–June quarter.

This was caused by a sudden slowdown in consumption stemming from delays in paying both civil servant salaries and government procurement bills from the second half of May, which in turn resulted from decreased fiscal spending due to local government revenue shortfalls.

This problem was clearly recognized by the time the GDP and other key economic indicators for the April–June quarter were released in mid-July.

By the end of July, the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) met to decide on the economic policy management strategy for the remaining months of this year.

No particular novel measures were announced. Nevertheless, because the economy markedly slowed down from the second half of May onward, it was believed that the central government had directed local governments across the country to implement economic prop-up measures starting in July.

It was predicted that this policy would prove effective and result in a measure of improvement from August in consumption, infrastructure construction investment, industrial production, and other key economic indicators.

However, the key economic indicators for August released in mid-September showed a decline in industrial production, service production, consumption, and investment, among others.

I surmise that these figures have astonished all economists who analyze the Chinese economy.

The situation did not change much in the figures for September and the July–September quarter that were released in mid-October.

3. Factors behind continued economic stagnation in the July–September quarter

Soon after the key economic indicators were released for the July–September quarter, in late October, I visited Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai to interview economists well-versed the Chinese economy. The aim was to hear their views on the state of economic policy management in the July–September quarter and what was behind it.

Their collective views suggest the following:

China implemented organizational reforms designed to further strengthen the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in the third term of the Xi administration.

In the past, the State Council worked with the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC) to make situational assessments needed for economic policy management, propose specific economic policy measures, and implement them subject to approval by the CCCPC.

Following the organizational reforms, however, the CCCPC assumed the role of assessing economic conditions and deciding what to do about them based on the policy of strengthening the CPC’s leadership, while the State Council took on the role of executing measures as directed.

In short, the authority to assess economic conditions and propose specific measures to deal with them was transferred from the State Council to the CCCPC.

Symbolically, this transfer put an end to the practice in which the Premier of the State Council gave a press conference following the National People’s Congress (NPC) every March.

In the past, it was customary for the Premier to talk to reporters about decisions made at the NPC. It was announced, however, that the press conference will not be held from this year.

Another change was that the Premier was not among the drafting members at the Third Plenary Session of the Central Committee which determined the medium- to long-term strategy for economic policy management.

This was an outcome of the transformed national governance system and the strengthened leadership of the CCCPC.

The delayed policy response that invited the economic stagnation of the July–September quarter can be attributed to the inadequate functioning of this new governance system.

Traditionally, the relevant departments of the State Council noticed economic anomalies, immediately analyzed what was behind them, proposed necessary policy responses to the CCCPC, and promptly implemented them subject to approval by the CCCPC.

Under the new governance system, however, the State Council needs to wait for directions from the CCCPC. Accordingly, it has become hesitant to proactively make policy proposals.

There was yet another misfortune.

The Third Plenary Session of the Central Committee was held in mid-July, during which key economic indicators such as GDP were released for the April–June quarter. The CCCPC did not have much time for in-depth analysis of the changes in economic indicators.

Consequently, the end-of-July meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) was held without detailed analysis of what was behind the economic slowdown and without the recognition of a strong sense of urgency.

It was surmised that as a result, even in and after August, the CCCPC did not direct the State Council or local governments to further strengthen economic prop-up measures.

It was not until the two important meetings – the Third Plenary Session and the PSC meeting – closed that CPC leaders visited the provinces. They came to deeply recognize the stern realities there as late as August.

With that recognition, they began moving in earnest to implement specific measures from September. It was in that context that President Xi Jinping visited the provinces.

The CCCPC issued a strong direction to the State Council. On September 24, it began to announce economic stimulus measures centering on finances, real estate, and stock markets.

In November, specific fiscal measures to support local government finances were announced.

These measures are expected to gradually prove effective and turn the economy for the better.

If such decisions had been made in July or August, the economy would have been turned for the better sooner.

4. Analogies between China’s Communist Party and government and Japanese firms

Problems caused by the above-mentioned shift in governance system have much in common with problems facing large Japanese firms.

From 2021, large Japanese firms are obliged to appoint outside directors for better corporate governance.

Earlier, in 2010s, outside directors at many Japanese firms began to exert a significant influence on the decision-making process at their board of directors.

It is reasonable to believe that appointed outside directors often help improve corporate management by offering apt insights based on their vast experience and accumulated knowledge as far as their fields of expertise are concerned.

With regard to China business, however, few outside directors have such experience or knowledge.

For this reason, I frequently hear complaints that outside directors at many Japanese firms often express irrelevant views, thus hindering management from making appropriate corporate decisions.

In July last year, the Counter-Espionage Law came into force. More recently, a pupil at a school for Japanese expatriates in Shenzhen was stabbed to death. The Chinese economy is not as brisk as it was in the period of rapid economic growth.

Many media reports focus on economic security risks.

I hear that many outside directors at Japanese firms use such general information as an important criterion to voice caution regarding these firms’ operations in China.

However, a look at the realities of China business from the perspective of Japanese firms’ representatives in China shows that not a few such firms have the prospect of steadily expanding the markets of their products in China for better performance, not affected by such a general state of affairs.

In that case, local managers in China suggest to their head office that it should be more aggressive in expanding business in the country. Their suggestions, however, are often denied without being able to persuade the board of directors at the head office, who are influenced by negative or cautious views expressed by outside directors.

In addition, there is a growing tendency at large Japanese firms that operational departments wait for direction from top management out of consideration of a greater emphasis on compliance.

As a result, delayed or erroneous decisions at the board of directors have serious consequences more and more often by hindering the development of China business.

Such problems with Japanese firms have much in common with the above-described problems facing the Communist Party and government of China.

While the adverse effects from problems with Japanese firms are limited in scope, any problem with Beijing’s policy management could have much more far-reaching effects, affecting the global economy.

I hope that the CCCPC and the broader Chinese government will properly recognize the essence of such problems and promptly implement measures to solve them.