Media International Exchange 2023.12.01

The Source of Pessimism on China’s Economy Is the Chinese Themselves

The key to recovery is the ability to implement policies that stimulate investment and consumer sentiment

The article was originally posted on JBpress on September 19, 2023

1. The source of pessimism on China’s economy is the Chinese themselves

The world is closely watching the slowdown of the Chinese economy.

In Washington, D.C., where I was staying in early September, a discussion on the current state of the Chinese economy by prominent experts was broadcast online and attracted a great deal of attention.

To the best of my knowledge, while experts well-versed in the Chinese economy in Japan, the U.S., and Europe generally view its current state relatively calmly, some economists and experts on diplomacy and national security not specialized in it share a pessimistic view.

In the U.S., I often heard that there were expectations that a slump in the Chinese economy might reduce the Chinese threat.

However, it seems that Chinese businesspeople and consumers themselves are the most pessimistic about the current slowdown in the Chinese economy.

One example reflecting this pessimistic view is that China could be headed for a Japanese-style economic recession, i.e., China’s Japanization.

During my visit to China in late July, I was repeatedly asked by Chinese economists and businesspeople about the possibility of China becoming like Japan in the 1990s.

The pessimism they transmit is considered to be one of the main reasons for giving the world a more pessimistic than realistic view.

2. Why the Chinese are in psychological shock

That being said, their pessimism seems understandable.

After the collapse of the bubble economy in 1990, the Japanese economy fell into a severe long-term economic recession. Western countries were also afflicted with a serious economic malaise after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

People in Japan, the U.S., and Europe, who have experienced these difficult times, know firsthand the severe economic stagnation that follows the collapse of an asset bubble.

In comparison, although the current economic downturn in China has not yet reached that level, many Chinese are extremely pessimistic at present.

The reason for this is that the Chinese people have not experienced any severe economic malaise since 1990.

In 1989 and 1990, the real GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate fell below 5% for two consecutive years, to 4.2% and 3.9% respectively, in part owing to a change in economic policy management against the backdrop of the Tiananmen Square protests and other events.

The real GDP annual growth rate then averaged 10.5% for the 20 years from 1991 to 2010 and reached an average of 7.3% from 2011 to 2019.

The lowest rate during this period was 6.0% in 2019.

Starting from the following year, the economy was lackluster for almost three years owing to the spread of COVID-19.

This three-year slump was considered unavoidable as it was caused by the special circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even in the doldrums, China’s economy remained much stronger in 2020 and 2021 than those of other developed countries in the world while supported by success of Beijing’s zero COVID policy.

It was in 2022 that the economy in China started to deteriorate rapidly, as the zero COVID policy stopped functioning well owing to the emergence of the new highly infectious Omicron strains.

With the unexpected end to the zero COVID policy in December 2022, it appeared that China had overcome the temporary disruption, and its economy was gradually normalizing from late February 2023.

It is natural that many Chinese expected the economy to bounce back to at least 2019 pre-pandemic levels. In fact, it was recovering relatively well until around March.

From April onward, faced with a variety of negative factors, Chinese citizens began to realize that that the reality would not live up to their expectations.

The weakness in China’s economy became all the more apparent when the Q2 (April-June) GDP growth and other major economic indicators were announced in mid-July.

At the time of the announcement of the Q1 (January-March) growth in April, it was expected that the economic recovery would continue steadily into Q2.

Quite a few observers had bullish expectations that real GDP growth rate could exceed +8% y/y in Q2, considering the rebound from the low growth in the same period of the previous year (+0.4% y/y real GDP growth in Q2 2022) attributable to Shanghai’s COVID-19 lockdown.

However, the actual figure announced was 6.3%, much lower than the immediately preceding market forecast (6.9-7.0%).

In particular, the indicators measuring consumption of goods and real estate worsened.

These figures gave many Chinese a psychological shock. There are concerns that the real growth rate may not reach 5% for the full year.

Of course, the recovery of the real economy was also slow.

Nevertheless, looking at the current state of the economy in China dispassionately, you will find that it is not as bad as it was in Japan in the 1990s or in Western countries after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. This point is explored below.

3. Misconceptions about the ‘Japanization’ of the Chinese Economy

It is quite understandable that the Chinese, who had not experienced a full-fledged economic recession since 1990, would feel pessimistic about their economic future when faced with an unexpected economic slowdown despite the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overcoming the first and second oil crises after 1973, Japan suffered a similar psychological shock in the early 1980s.

The real GDP growth rate of the Japanese economy in FY1972, immediately before the first oil crisis, was 9.1%.

However, after getting over two oil crises, the real growth rate in the first half of the 1980s plunged to around 3-4%, leading to widespread pessimism about the economic future of Japan at that time.

Partly owing to this, the Japanese government implemented excessive pump-priming measures, which resulted in the emergence, expansion, and bursting of Japan’s economic bubble.

In order not to repeat the mistakes of Japan, Beijing has been making efforts since the 1990s to learn thoroughly from Japan’s experience.

This is one of the reasons for the current cautious management of economic policy in China.

Against this backdrop, worries about Japanization spread immediately after the release of Q2 economic data.

With that being said, the situation of the Japanese economy in the 1990s was far harsher than that of the Chinese economy today.

Housing prices nosedived in all major cities, including Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, and stock prices also plummeted.

Financial institutions withdrew their loans, and companies cut back on capital investment and employment, heading toward contracted equilibrium.

A look at the Chinese economy today finds that bank lending and capital investment have maintained positive growth, and employment, with the exception of the young, has generally been stable.

No one in China is worried about the risk of a major bank failure, which Japan experienced from the late 1990s.

If you ask Chinese people whether they think the five biggest banks, such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and the China Construction Bank (CCB), will go bust, they will all immediately say no.

When I give the above explanation to Chinese people, they understand that China will not become like Japan, but recession fears have not receded or dissipated.

4. The Chinese economy has been settling down since July

On September 15, the National Bureau of Statistics of China released its key economic indicators for August.

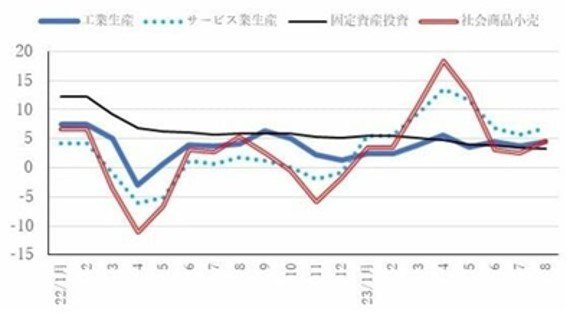

According to the released data, the Chinese economy remained relatively stable from June to August. Industrial production, service production, and consumption all declined slightly in July, but rose in August, and when the three months are taken as a whole, they have remained more or less the same. (See Chart 1.)

Fixed asset investment alone has been on a gradual decline since the beginning of 2023.

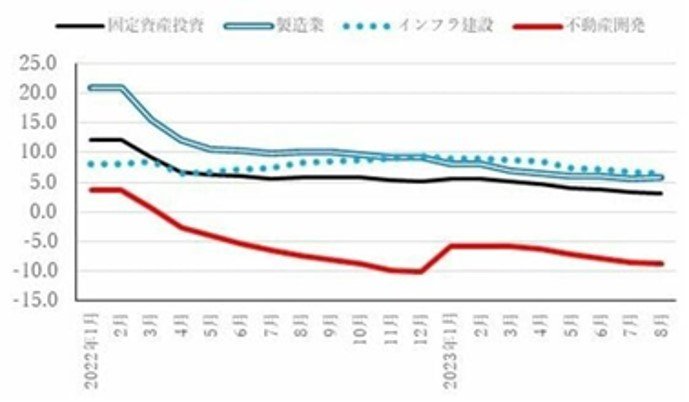

By sector, manufacturing, infrastructure construction, and real estate development have all been on a downward trend, but manufacturing and infrastructure construction have remained favorable at 5.9% and 6.4% respectively for the January-August period. (See Chart 2.)

With regard to the manufacturing sector in particular, the private sector jumped by +8.5% y/y in the January-July period, exceeding the pre-pandemic level in 2019 (+2.8% y/y for the full year).

Meanwhile, investment in real estate development continued to chalk up significantly negative growth (-8.8% y/y for the January-August period).

This has had an adverse effect not only on investment, but also on consumption of furniture, appliances, interior decorations, and other items, as well as on local government finances, and is dampening the spirits of Chinese people.

Chart 1 Major Economic Indicators (y/y)

Note: All monthly figures for fixed asset investment are year-to-date y/y.

Source: CEIC.

Industrial production(blue)

Service production(dot)

Fixed asset investment(black)

Retail sales of consumer goods(red)

Chart 2 Fixed Asset Investment by Sector (year-to-date y/y)

Source: CEIC

Fixed asset investment(black)

Manufacturing(blue)

Infrastructure construction(dot)

Real estate development(red)

5. China’s economic outlook

The recovery of the Chinese economy depends on the future management of economic policies.

Beijing has a lot of issues, including the dragged-out slowdown of the real estate market, deterioration of local government finances, youth unemployment, and the ongoing dispute with the U.S., but the most important issue of all is whether the concrete results produced by its policies will brighten the mood of business managers and consumers and give them confidence in a future economic recovery.

In particular, the Common Prosperity Policy which has been implemented since the year before last and the zero COVID policy last year have dampened the private sector’s positive motivation.

Confidence in government policy management has also declined. The key to getting the economy back on the growth track is to improve the private sector’s sentiment.

At this point, there has been no change in the two major basic policies that have been in place for some time. The first is the “two unwavering policies” namely giving importance to both the public sector and the non-public sector as important components of China’s basic economic system.

The second is to concentrate on promoting high-quality development.

In China, the term “high quality” is understood to be intended to cover the realization of common prosperity and the emphasis on national security.

While these basic policies are important, it is also true that private businesses and consumers have lost steam as the government has reiterated these terms.

The reality is that state-owned enterprises still have many advantages over private enterprises in terms of bank lending conditions, market access, etc.

In order to break out of the current difficulties, it is necessary to implement a new basic policy that goes beyond these two policies and will inspire private businesses and consumers, and to take concrete steps that clearly support the new policy.

Up until the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government had long conducted economic policy management in an admirable manner under the supreme commander Vice Premier Liu He, but that supreme commander is no longer in office.

The focus is now on what kind of policies his successors will be able to present and implement quickly and thoroughly throughout the country.

The core of these policies will be the medium- to long-term basic policy for policy management, which will be presented at the Third Plenary Session scheduled for this autumn.

The content of the medium- to long-term basic policy for policy management that will be presented there will test the true value of Vice Premier Liu He’s successors.

I hope that the Chinese economy, which has played a crucial role in supporting the global economy since the 2010s, will steadily recover under the new regime.