Media Global Economy 2023.01.24

The world’s leading companies remain positive toward the Chinese economy even as it slows:

They maintain unwavering long-term strategies amid growing pessimism

The article was originally posted on JBpress on November 18, 2022

1. How much is the Chinese economy slowing?

The Chinese economy has been slowing markedly since Shanghai was imposed a lockdown from late March to May this year under the zero-COVID policy.

Real GDP (gross domestic product) grew only 0.4% in the second quarter and 3.9% in the third quarter from a year earlier.

Monthly data for October, released on November 15, shows that China’s production, exports, and investment all slacked compared with the previous month.

Consumption remarkably slowed down. The year-on-year change in total retail sales of social consumer goods was minus 0.5% as against plus 2.5% for September.

Let us take a closer look at year-on-year changes for October for these four categories. Exports grew 7.0%. This figure seems fairly good at first glance but actually represents a fall in real term because export prices have posted double-digit growth continuously since the first quarter of this year.

Last year, as its zero-COVID policy paid off, China was the only country in the world whose economy almost returned to normal, and Chinese firms increasingly substituted production by foreign firms. However, this year, the trend has been reversed.

This reversal in trend has been accelerated partly because the United States reduced imports from China. In the US, domestic demand has shifted in focus from goods to services as COVID infections have been subsiding.

In the category of consumption, the transport, restaurant, and hotel industries are sluggish owing to the Zero-COVID policy. A faltering property market takes a toll on the consumption of furniture, consumer electronics, interior decorations, and the like.

Investment in property development is markedly on the decline over the long term. Investment is also sluggish in steel, cement, glass, construction machinery, and other sectors related to housing and office construction.

A stagnant property market makes it difficult for local governments to secure fiscal financing through property development, resulting in local governments facing inadequate fiscal revenues.

In addition, regional economies are in dire fiscal and financial straits, as properties with declining prices will likely become bad debts, in turn increasing the risk that small and medium-sized financial institutions will go under.

Under these circumstances, it is unlikely that China’s real GDP growth rate for this year will reach even 4%, much less the annual target of 5.5%.

There are many contributing factors in addition to the Zero-COVID policy. They include a large number of university graduates out of work, an increasingly sluggish property market, the prospect of a slowing global economy due to inflation control measures by governments, the intensifying US-China rivalry, a declining population due to a lower birthrate, and lower motivation on the part of private enterprises as a side effect of the common prosperity policy.

National travel restrictions stemming from the lockdown of Wuhan in 2020 had only a short-term impact, allowing the economy to rebound quickly.

This time around, however, the economy is in a more serious condition. Getting the economy out of it is not easy. In fact, the Chinese economy is experiencing its most serious stagnation in 32 years since 1990 when the Tiananmen Square incident triggered a major economic downturn.

As such, many businesses that continued to perform well have no choice but to cut their workforce now. A young manager in his thirties told me that he had never experienced such a harsh economic climate in his life.

2. Factors that increase pessimism about the Chinese economy

It was in such a difficult economic situation that the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) was held. The congress revealed the new lineup of the CPC’s leadership.

The new lineup came as a great surprise. Politburo member and Vice Premier Hu Chunhua, viewed as a shoo-in for premiership, was demoted to a Central Committee member. Other strong candidates from the Communist Youth League of China were excluded from important posts.

International observers predict that this shake-up will concentrate more power on President Xi Jinping and undermine the capacity for economic policy management during his third term. Those in Washington, D.C. among others are stepping up their criticism toward China.

Some experts in China see the new lineup as a group of executives with reliable practical skills. This view is not generally shared in Japan or the US.

In these two countries, the new lineup is considered yet another piece of evidence that justifies pessimism about China. This is because like-minded experts and specialists are reinforcing their pessimism in what is known as the echo chamber phenomenon.

Until last year, pessimism about China had been stronger in the US than in Japan. More recently, however, there has reportedly been renewed pessimism about China among government officials and academics in Japan.

This can be interpreted to mean that Japanese people with close ties to the US are increasingly involved in this echo chamber phenomenon.

In addition, Japanese firms have turned wary about China after Japan enacted and promulgated the Economic Security Promotion Act last May. In short, they are now more cautious about business opportunities in China.

Because of the dominant pessimism over China, a growing number of Japanese experts feel that the Chinese economy might sink as the Japanese economy did in the 1990s.

I hear that meetings within the Japanese government and business communities as well as among scholars are such that participants have difficulty in engaging in discussions unless they share a pessimistic view of the Chinese economy.

3. Top-tier global corporations remain aggressive in China business

As described above, experts and the media in Japan, the US and European countries have recently been tipping markedly toward pessimism about the Chinese economy.

However, discussions by people who support such a pessimistic view are often not based on hard evidence. Many of these people are not experts on the Chinese economy.

In September, I started to interview experts in the US and the EU, as well as Japanese corporate executives and government agency officials based in China, in person or online. I asked them about their views on trends in investments in China by top-tier firms based in Japan, the US and Europe.

Their input can be summarized as follows:

US semiconductor manufacturers continue their supply to China in close contact with the US Department of Commerce, so there have been no major disruptions in production by Chinese manufacturers, except in a few state-of-the-art technology sectors.

American universities and high-tech firms continue to welcome talented engineers and technicians from China, and top-notch Chinese talent in the US are not going to return to China.

Germany welcomes major Chinese firms doing business in the country. Last year, three major Chinese battery manufacturers began to construct new plants in Germany.

In parallel, EV exports from China to Europe are swelling rapidly.

On November 4, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz visited China with representatives from 12 giant global corporations based in Germany to meet with President Xi Jinping.

This visit is seen to represent Germany’s policy to decouple economics from politics.

A Japanese manufacturer that is performing well in China has recently increased the numbers of new hires at its plants. It has secured new hires more successfully than before.

This is because it succeeded in tapping into the service-sector labor force made redundant as a result of the zero-COVID policy.

Another Japanese company is preparing to get off to a flying start in the resumption of its investment in China after the Zero-COVID policy ends.

Murata Manufacturing announced this November that it will build a new plant in Wuxi. The investment amounts to 44.5 billion yen, the largest investment yet for the company.

Japanese financial institution executives, government officials, and economists see no major changes in Japanese firms’ willingness to invest in China and no changes in their long-term strategies either.

All these accounts reflect the realities surrounding major corporations based in Japan, the US and Europe. They clearly differ from what is generally believed in Japan with regard to the attitudes of foreign firms, especially Western companies, toward investing in China.

In doing business, top-class companies based in Western countries decouple economics from politics, or more specifically, decouple their operations from the diplomatic policies of the governments of these countries.

By contrast, Japanese businesses exhibit what can be described as a diffident attitude toward the Japanese government, according to some executives at major financial institutions.

Japanese companies that want to survive fierce competition with Western counterparts in the global market have no choice but to decouple economics from politics in their operations as their Western competitors do.

In this particular aspect, however, there still seems to be a perception gap in Japan.

4. The task facing Japanese firms

It is clear that in all likelihood, the period of rapid economic growth has come to an end in China. Nevertheless, the Chinese economy will likely maintain a growth rate of at least 3–4% for the next ten years or so.

It is also clear that top executives at leading global corporations based in Japan, the US and Europe all agree that no market in the world is more attractive than the Chinese market from a long-term perspective.

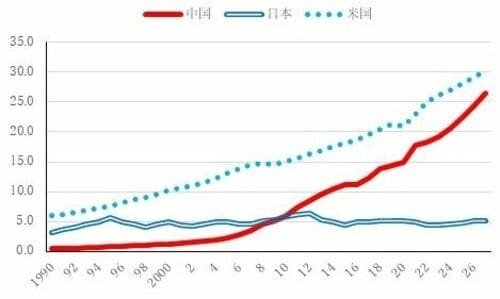

The World Economic Outlook of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised downward its projections for the Chinese economy in October. But its outlook that the Chinese economy will eventually rival the US economy remains unchanged (see the Chart below).

Such a long-term outlook is one major reason why top executives at the world’s leading companies will not change their attitudes toward investing in China.

The allure of the Chinese market lies not only in its expanding size but also in the continued commitment of local governments across the country to attract foreign firms and extend substantial support to them.

Luring blue-chip foreign firms is key to revitalizing Chinese regional economies that have sustained economic development over the long term by leveraging the open-door policy.

Although the Chinese economy is expected to face an uphill battle, local governments are stepping up their commitment to attracting blue-chip foreign firms.

Nominal GDP of Japan, the US and China (in trillion dollars)

Source: IMF, “World Economic Outlook,” October 2022

Meanwhile, some experts point out the possibility that the US will step up pressure on China, and thus it will become difficult for US and Japanese businesses to provide cutting-edge technology to China, leading to some negative impact.

Yet only the cutting-edge segments of a few industries will be affected. These segments account for a rather small portion of total investment in China.

This is why experts in China stress that the impact will not be as serious as the media reports.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the Chinese economy is losing steam. Even so, major global corporations share the view that the relative advantage of the vast profit opportunities that the Chinese market offers will not diminish soon.

Influenced by the growing pessimism over the Chinese economy, an increasing number of firms will consider withdrawing from China or scale down their operations in the country.

Investments by such firms, however, are small and represent only a small portion of the total investment in China from Japan, the US and Europe, as most of these businesses are performing poorly in China.

The possibility that such withdrawal and scale-down by firms with small investments will bring down the total investment will be even lower if the Zero-COVID policy is eased and major businesses begin to invest heavily in China again.

If Japanese firms misinterpret such a state of affairs surrounding investments in China and limit their exposure to the Chinese market, they will drop out of the cut-throat competition among top-tier global corporations based in Japan, the US and Europe.

They should not be deluded by growing pessimism toward China due to the echo chamber effect. Instead, they should gather accurate and timely information on local market trends as well as trends in investments in China by leading global corporations based in Japan, the US and Europe and reinforce efforts not to lose out to the competition. Otherwise, they have little chance of survival in the Chinese market, and by extension, in the global market.