Media Global Economy 2023.01.12

Lies and deceptions behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act

The truths that you should know so as not to be deceived

The article was originally posted on RONZA on November 2nd, 2022

The government is working to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act (“the Basic Act”) not least to enhance Japan’s food security. It is important to remember here that mistaken facts or premises will only lead to a mistaken conclusion.

Ideas generally believed to be true about agriculture and rural areas in Japan are often false or phony. Agriculture and rural areas in Japan have undergone substantial changes. For example, the numbers of farmers and farm households, which had remained almost flat for more than a century, have been on a sharp decline since 1965. However, the Japanese public’s perception of the country’s agriculture and rural areas has remained unchanged because most Japanese people have distanced themselves from such areas and the industry. Even people from rural areas know little about what is going on in agriculture and rural areas.

Who fabricates lies and takes advantage of them?

The “agricultural policy triangle” does! The triangle comprises the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA), the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), and the lawmakers of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who represent agricultural interests. The agricultural policy triangle capitalizes on such lies or even fabricates them to lead the public to a certain conclusion. Examples include such statements as “farmers are reluctant to lend their farmland because they have inherited it from their ancestors,” “Japan’s agriculture will be devastated if farm tariffs are removed,” and “domestic farm products are safer to eat and more stable in supply than imports.” This time around as well, the triangle maintains that a smaller farming population would undermine the stable food supply.

Such information is manipulated so cleverly that many people believe it. Reporters at Japanese major newspapers and public broadcaster NHK cannot see through the fables circulated by the agricultural policy triangle because the same reporters cover agricultural policy for only one to two years. They seem to have no time to read my books as well. This is why they report as the MAFF says. Laypeople who lack enough expertise to criticize such false reports have no choice but to take them at face value.

Agricultural researchers at universities and research institutions are afraid that their positions will be undermined if agriculture and rural communities diminish. Desiring to see agricultural protection remain in place, these researchers make a false assertion, effectively assisting the agricultural policy triangle. They are not necessarily well informed about the current state and history of agriculture in Japan or about agricultural policies and the domestic and international environment surrounding the industry, and so they write articles and books on mere assumptions. Such books fill the shelves on agriculture in large bookstores in cities. Many people who lack knowledge about agriculture believe what is written by such researchers as well as by the government and the MAFF.

Do farmers and people otherwise engaged in farming have accurate knowledge about the industry? Many of them do not. Agriculture comes in many forms, including rice farming, vegetable and fruit farming, and livestock farming. Vegetable farmers, who are often cited as successful farmers, know little about rice or livestock farming. They may have sufficient knowledge about their own farm work and management, but they may not know much about general situations and policies surrounding agriculture.

At a demonstration held in Tokyo to oppose the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, a vegetable farmer from a province shouted that he would be forced out of business if Japan participated in the TPP, oblivious to the fact that the import tariff on the kinds of vegetables he grew was only 3%. Even farmers are not immune to the propaganda of the JA and the MAFF. When I was a young official, I was astonished to hear a farmer in my hometown talk about the MAFF’s propaganda as if it were the opinion of his own. His firm belief in the information manipulated by the MAFF scared me.

In revising the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act, the government says it will listen to people from all walks of life through the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies. Yet the material the MAFF presents to the Council is designed to lead the discussions to certain conclusions. It is hard to believe that Council members not fully familiar with food, agriculture, or rural areas can discuss the matter without being deceived. They tend to believe that the MAFF provides accurate information although the ministry, being part of the agricultural policy triangle, is no longer a “servant of the people.”

This article presents a set of bona fide facts needed to revise the Basic Act.

Farmers are a minority in rural areas

The mere act of visiting rural areas does not suffice to assess the realities there. Most Japanese people except those living in rural areas believe that such areas are inhabited mostly by farmers.

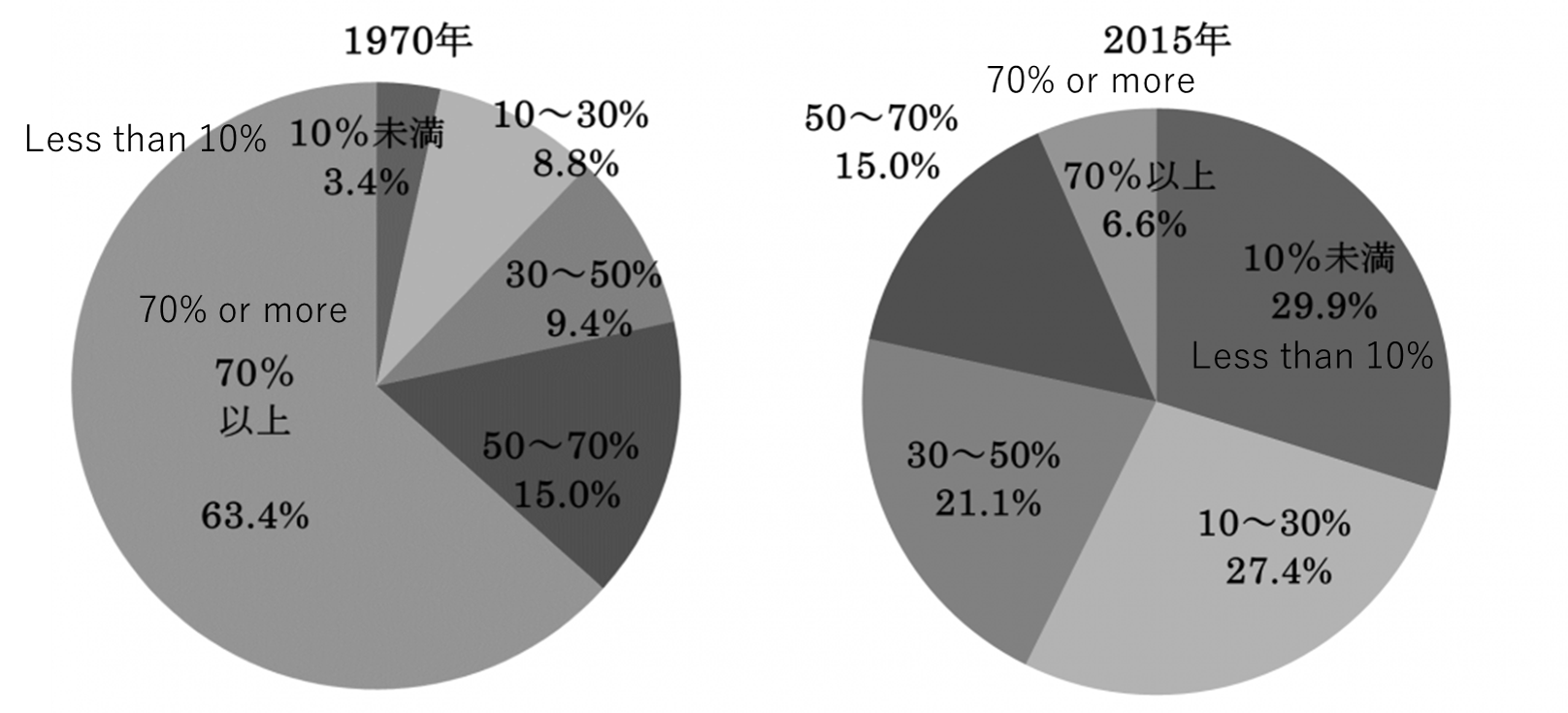

However, the proportion of rural communities where farm households accounted for more than 70% in Japan plunged from 63.4% in 1970 to 6.6% in 2015. By contrast, the proportion of rural communities where farm households represented less than 10% stood at 30% in 2015. Rural communities where farm households made up less than 30% accounted for 58% in the same year.

Rural communities where farm households constitute a minority have increased significantly in number, while traditional rural communities where farm households make up an overwhelming majority are disappearing, if not already disappeared. Farm households are a minority, not a majority, in rural communities.

Changes in the number of rural communities by proportion of farm households

Source: Compiled by the author from MAFF, “Census of Agriculture and Forestry”

Note: A rural community refers to a naturally occurring local community where households have developed community and blood ties to form groups and social relations of various sorts. It constitutes a basic unit for social life.

As non-agricultural industries developed greatly after the end of World War II, a substantial number of farmers abandoned farming and took non-farming jobs. As new industrial cities began to be constructed across the country in 1964, factories popped up near rural areas. This allowed people in rural areas to commute to work while continuing to live there, obviating the need to move out.

As a result, “workers’ households” headed by salaried workers at government offices, companies, and factories have grown in number. Even among the households who have continued farming, “part-time farmers” who work as salaried workers during the weekdays and work as farmers only on holidays have increased in number as well.

This state of affairs cannot be seen just by visiting rural areas. Even people who live in regional cities or towns near to rural areas are not aware of it. Spatially, paddy and upland fields take up most of the land in rural areas even today. People who have seen this are deluded in believing that farming is the dominant industry in rural areas. Business suit-clad salaried workers living in rural areas cannot be seen during the daytime there.

In this way, the status of agriculture has been declining even in the provinces. Promoting agriculture will not lead to the revitalization of rural areas or the provinces.

Is rice farming hard work?

Agriculture has changed as well. Farmers have been freed from physically demanding farm work. Thanks to mechanization, farmers no longer have to plant rice seedlings one by one by hand or to harvest rice with a sickle. Thanks to agrichemicals, farmers no longer have to remove weeds by hand as well. Women who have been hunchbacked as a result of hard farm work are no longer seen in rural areas. Chemical fertilizers, agrochemicals, and farm machines have taken the place of such physically demanding work.

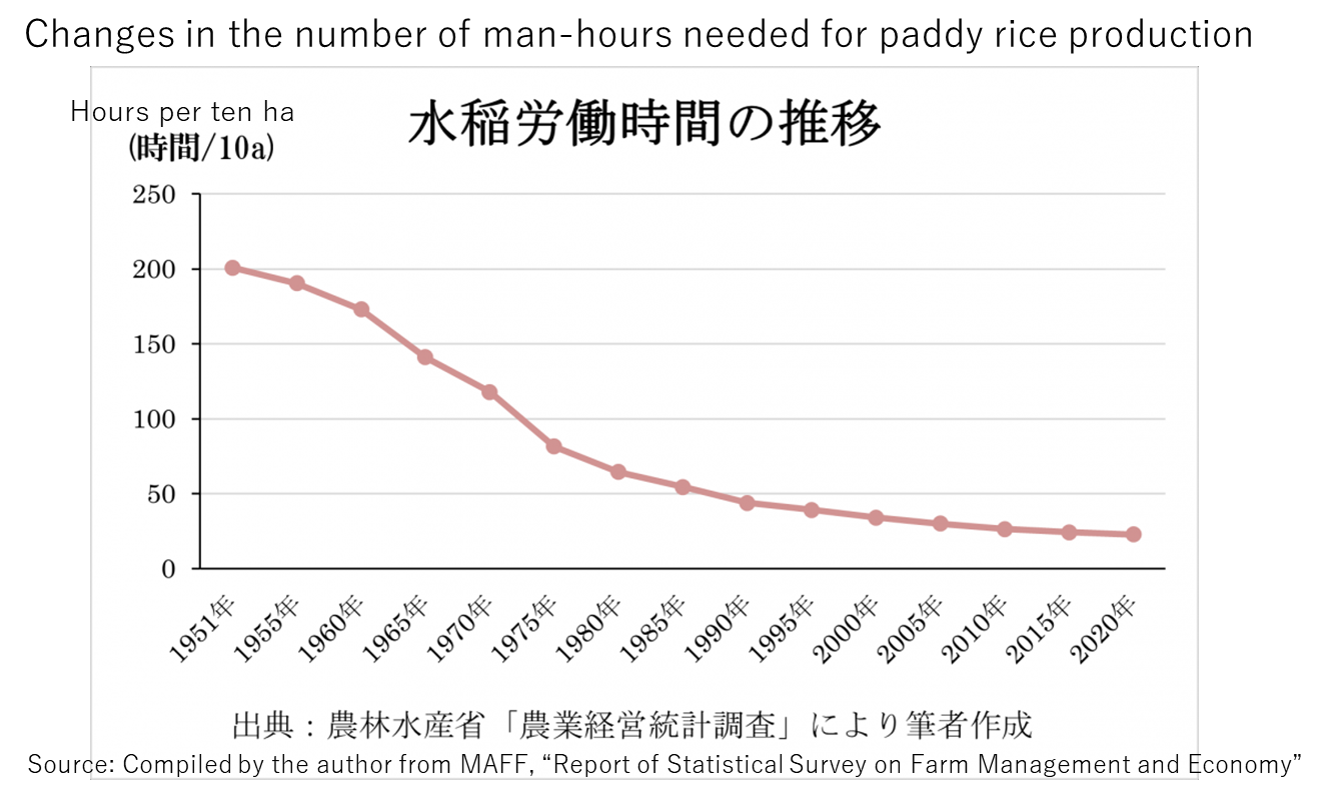

The annual number of man-hours required to grow rice per ten ares plummeted from 201 in 1951 to 22.8 in 2020. Mechanization of farm work is pronounced in rice farming. A sharp drop in the number of man-hours needed to grow rice means that farm work only on weekends suffices for an average area of paddy fields.

There is a saying that just as the Chinese character for rice can be read as eighty-eight, rice farming requires as many as 88 kinds of work. This saying is no longer relevant today. On the assumption that farmers work eight hours a day, the annual average number of days worked by farmers with about one hectare of rice paddies dropped from 251 in 1951 to 29 in 2020. This number is only 14 for farmers with 0.5 hectares of rice paddies. The fact that weekend work is all farmers need to do has also accelerated a shift toward part-time farming.

In the age of rapid economic growth in Japan, the buzzword “mechanization-induced poverty” was on the lips of farmers who needed to buy costly farm machines. Farm machine manufacturers and agricultural cooperatives gained a handsome profit by selling such costly equipment. Part-time farmers needed farm machines to work as salaried workers during the weekdays. Unlike the phrase “mechanization-induced poverty” suggests, mechanization did not work against them because the full cost of depreciation of farm machines was factored in the government’s rice purchase price. As a result, many rice farmers have become part-time farmers.

Are farmers poor?

Agricultural policymakers say they aim to increase the income of farm households. The government went as far as to endorse the target of doubling agricultural and rural income at a Cabinet meeting. This came after the ruling LDP released its 10-year strategy to double agricultural and rural income in 2013. Export promotion, the centerpiece of the latest government policy on agriculture, is supposedly aimed at raising the income of farm households.

Yet no political parties or media outlets challenge this target. This is because most Japanese people have a stereotypical view of farm households as living a pitiful existence and suffering poverty and hard work – the image of poor farmers before WWII.

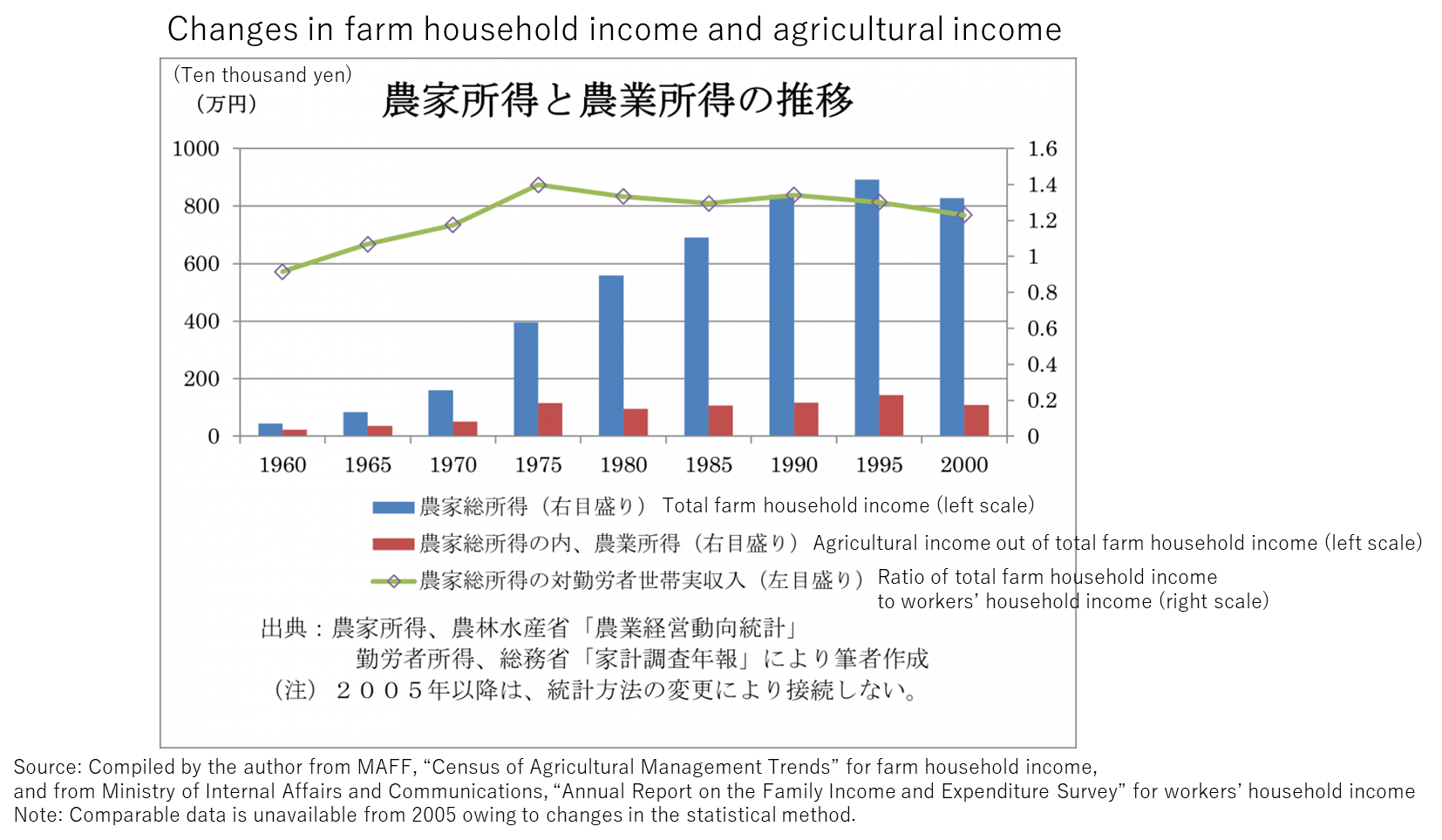

However, farmers today are different from prewar tenant farmers. Since 1965, farm household income has been well above workers’ household income. Farm households have become rich thanks to a shift to part-time farming, the conversion of farmland to residential use, and government protection and support. For over half a century, poverty has been non-existent in the agricultural industry and rural communities in Japan. Increasing the income of farm households could not possibly be an objective of agricultural policy in this country. On the contrary, Japan’s current policy on agriculture imposes a heavy burden on low-income consumers by keeping the prices of farm produce high to increase the income of farm households.

As industry moved into rural areas, factory workers in rural communities increased in number. Since 1965, farm households have outstripped workers’ households in terms of income. This has been made possible by an increase in income from non-farming work, not in agricultural income.

The figure below shows that farm household income has been above workers’ household income since 1965. The figure indicates an extremely small proportion of agricultural income in farm household income. It should be noted here that this is a reflection of the fact that an overwhelming majority of farm households are rice farm households.

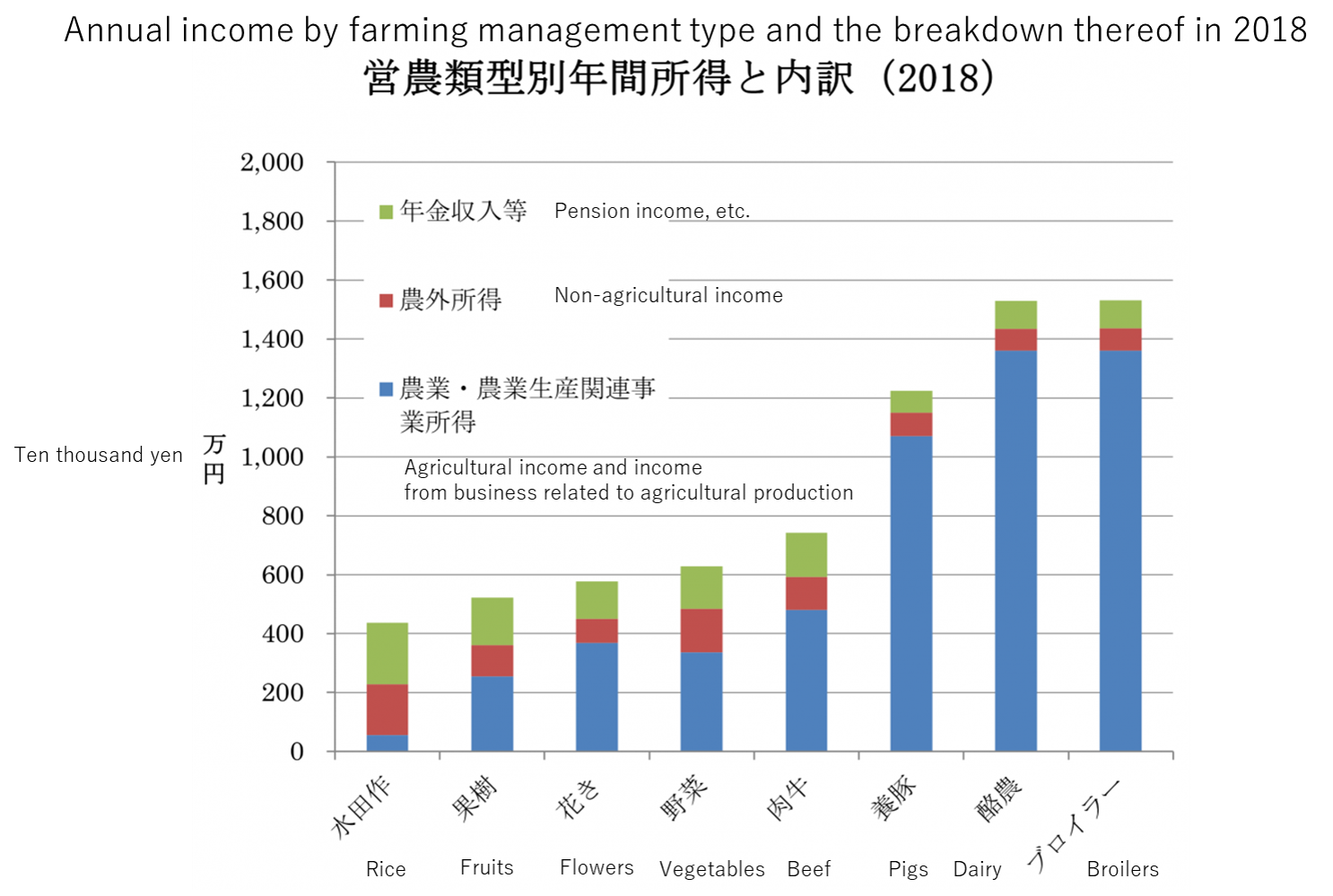

Farmers may be several times wealthier than you

When it comes to the farm household income of non-rice farmers, agricultural income accounts for a much larger share, as the figure below shows. Almost all the income of dairy farm households represents agricultural income. They earn several times more income than the average household headed by a salaried worker. A bizarre structure has been in place in which low-income consumers support rich farm households with high prices as well as ample subsidies.

Rice farm households are different. The proportion of their agricultural income is extremely small and the proportion of their non-agricultural income and annuities are extremely large. In short, many rice farm households are headed by salaried workers (part-time farmers) or pensioners (former part-time farmers). This is the result of high rice prices and the rice acreage reduction program, both of which have allowed even these high-cost farmers to survive.

Source: Compiled by the author from MAFF, “Report of Statistical Survey on Farm Management and Economy (Statistics by Management Type) (Individual Management)”

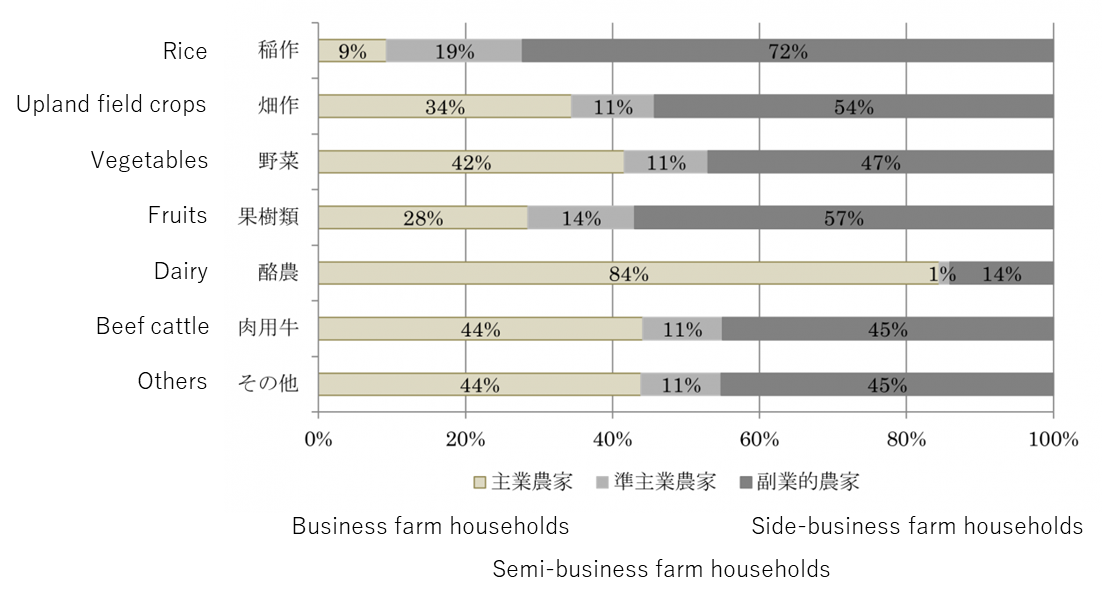

The biggest problem with Japan’s agriculture is that while 69% of commercial farm households cultivate rice for the purpose of selling the crop, the total sales of rice account for only 19% of the total sales of agricultural produce (as against about 50% around 1960). This indicates that Japan’s rice farming is an inefficient industry managed by numerous small-scale farmers. Business farm households account for 84% of dairy farm households but only 9% of rice farm households. The fact that only rice production is in such a state of affairs is the reflection and outcome of the skewed rice policy that has been in place over the years.

Breakdown of different agricultural sectors by type of farm household in 2019

Source: Compiled by the author from MAFF, “Survey on Movement of Agricultural Structure”

Does fewer farmers make the food supply insecure?

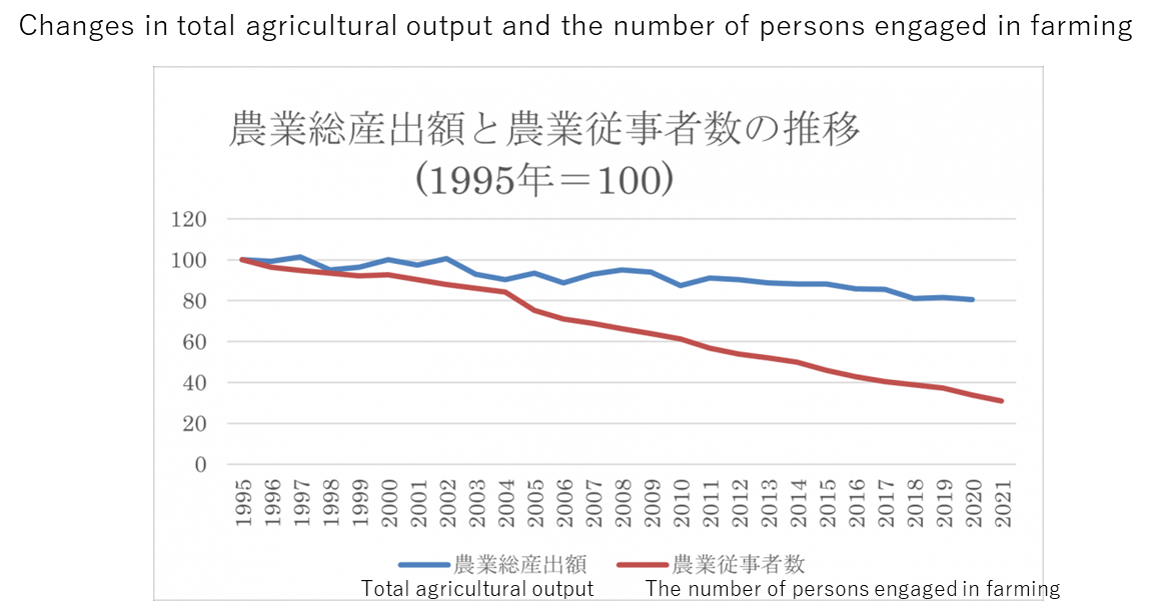

It is generally believed that a fall in the number of farm households or persons engaged in farming makes the food supply insecure. But this is a lie concocted by the agricultural policy triangle.

The number of farm households dropped from 6.04 million in 1955 to 1.03 million in 2020. During the same period, the number of persons engaged in farming plummeted from 19.32 million to 2.49 million, a decrease of 87%. The number of core persons mainly engaged in farming stood at 1.36 million as of 2020.

As the figure below shows, agricultural output (the real value adjusted for price fluctuations) did not fall as rapidly as the number of persons engaged in farming.

Source: Compiled by the author from MAFF, “Statistics of Agricultural Income Produced,” “Statistical Survey on Commodity Prices in Agriculture,” “Survey on Movement of Agricultural Structure,” and “Census of Agriculture and Forestry”

Over the past 60 years, the number of dairy farm households has fallen from 400,000 to 13,000, while raw milk production almost quadrupled from 2 million tonnes to 7.6 million tonnes. In dairy farming, production shrunk significantly in prefectures with high costs and grew in the northernmost prefecture of Hokkaido.

Rice farming can follow suit. Even if part-time farmers withdraw from the rice industry, business farm households will fill the void, leaving no problems with food production. As far as rice farming is concerned, the MAFF has ostensibly been calling for concentrating farmland on core farmers (business farm households and agricultural corporations) to expand the farm size in order to cut costs and improve competitiveness. For this to happen, the number of farm households needs to be reduced. What the MAFF is saying now contradicts what it has been saying all along.

The JA has consistently opposed the MAFF’s structural reform approach, stressing the need for diverse types of farm management, i.e., the need to keep small-scale farmers intact. Deep down, LDP lawmakers who represent agricultural interests agree with the JA. The same holds true for the opposition parties except the Japan Innovation Party. They all maintain that Japan’s agriculture and rural areas could not exist without part-time farm households.

The reality proves different, however. The number of farm households that earn their main income from jobs other than farming is now about 30% of the level around 1985. Yet the total area of farmland in Japan has not shrunk that much because business farm households have taken over much of the farmland thus deserted. Both the ruling and opposition parties hope to gain farm votes rather than to promote agriculture.

Is respecting small farmers a global trend?

Agricultural interests in Japan maintain that global agricultural policy now focuses on protecting small farmers. On December 19, 2018, the Japan Agricultural News, a daily newspaper of the JA, reported that the United Nations adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants. The editorial of this edition praised the declaration as being historic for family farmers, other people working in rural areas, and cooperatives that support them all around the world. It characterized the declaration as effectively urging Japan’s agricultural policymakers – which go against global trends and blindly embrace the free-market doctrine under the leadership of the Prime Minister’s Office – to think again. It went on to call on the Japanese government to take the UN declaration seriously, reflect the wisdom of promoting family farmers in its deliberations on how to revise the Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, and turn the wisdom into specific government measures.

But this is an egregiously false argument. The UN declaration focuses on “peasants.” A peasant is “a poor farmer or farm worker who has low social status – used especially to refer to poor people who lived in Europe in the past or to poor people who live in some countries around the world today,” according to Merriam-Webster’s Advanced Learner’s English Dictionary. Peasants correspond to serfs in medieval Europe and mizunomi byakusho (literally water-drinking peasants) or poor tenant farmers in prewar Japan. There are farmers but not peasants in developed countries today.

The JA’s argument that the UN declaration seeks to protect family farms is a fabrication by two-fold misconstruction – deliberately misinterpreting peasant as small farmer and then smaller farmer as family farm(er). Being small in size is a condition for being a peasant. Yet rich part-time farmers in Japan are small farmers but not peasants. Large farmers in the United States are family farmers but they are not small farmers. Above all, the term “family farm(er)” does not appear in the declaration even once.

If you read the UN declaration carefully, it will become crystal clear to you that “peasants,” a key term the declaration focuses on, refers to farmers in the developing world who face such challenges as poverty, hunger, unlawful arrest and detention, torture, the denial of the right to a fair trial, forced labor, human trafficking, slavery, the denial of the use right to use or own farmland, unlawful or illegal eviction, and the confiscation of their farmland.

The UN declaration calls for improving the social, economic, and political status of farmers who are in lower income brackets and discriminated against in the developing world, where the average annual per capita income is less than 0.3 million yen. There are no such farmers in Japan who need relief measures as called for in the declaration. Farmers in northeastern Japan who had no choice but to sell their daughters to survive the Showa Depression of the early 1930s would be eligible for such remedies. People at non-profit organizations who lobbied for the adoption of the UN declaration would be dumbfounded by the argument that rich Japanese farmers today, who earn more income than the average Japanese, should be eligible.

A half of farmers in the US are small farmers with total sales of less than 0.5 million yen. But they are part-time farmers, not poor peasants who have low social status. If JA officials visited such farmers and called them “peasants,” these farmers would point a gun at them. Western people would describe small farmers in Japan as affluent workers or pensioners who live in a house with a relatively large kitchen garden.

In the US, 97% of all farmers, including large farmers, are family farmers. Wheat farmers who cultivate 10,000 hectares in Australia, as well as Japanese large farmers in Tokachi and Ogata Village in northern Japan [both of which are known for their large farm size], are also family farmers. Conversely, many small farmers in Japan who engage in farm work alone only on weekends could not be described as “family farmers.”

The phrase “domestic production for domestic consumption” is deceptive

The catchphrase “local production for local consumption” is here to stay.

In reality, however, livestock products in Japan are de facto processed products made from imported corn. Udon and ramen noodles are made from imported wheat. If you stick to the idea of local production for local consumption, all you can eat is rice, vegetables, and fruits. If you insist that you eat only locally-made products, Hokkaido – which, with a food sufficiency rate of 200%, exports agricultural produce to other prefectures – will need to reduce production substantially.

Against this backdrop, the JA is now advocating the idea of domestic production for domestic consumption. Yet the argument that people in the southwestern region of Kyushu should eat farm products from Hokkaido rather than those from South Korea, which is nearer to the region, go against the idea of food mileage, which is discussed later. Why will “global production for global consumption” not do?

Agricultural interests in Japan argue that domestic production should lead to a more stable food supply. Then why has the JA been reducing domestic rich production?

As far as wheat and some other products are concerned, domestic products are more unstable in supply, poorer in quality, and higher in price.

The idea of food mileage itself is suspect. Production and distribution of food accounts for 20% of greenhouse gas emissions. CO₂ emissions largely come from the production phase, including the production of fertilizers and agrochemicals and the consumption of fuel for farm machines. Emissions from transportation represent only 4% of total emissions from food production and distribution. It is difficult to argue that Japan’s farm products, for which several times more agrochemicals are used compared to other countries, entail lower CO₂ emissions than imported farm products. Mutton produced in the United Kingdom emits four times as much CO₂ than mutton from New Zealand although it travels 18,000 kilometers to the UK.

CO₂ emissions vary depending on the transportation means. Road transportation by truck within the country emits more CO₂ than transportation by ship. In both freight and passenger transportation, Japan has seen a shift from energy-saving means of rail and ship to energy-consuming means of automobiles and aircraft. It is also difficult to argue that long-distance international transportation emits more CO₂ than short-distance domestic transportation. The idea of food mileage does not constitute a basis for justifying the goal of increasing food self-sufficiency.

Japanese farmers use large amounts of agrochemicals, eight time as much per hectare compared with their American counterparts. Small-scale part-time farmers who engage in farming only on weekends cannot spare much time and effort to control weeds. They just use pesticides to eradicate. Contrary to conventional wisdom, larger business farm households, which can afford to take more time for farming, are more eco-friendly. An increase in the number of part-time farmers meant more use of agrochemicals, resulting in the demise of living creatures in rice paddies. Wild storks that fed on them died out in 1971. The notion that Japan’s agriculture is eco-friendly is false.

More mysteries regarding Japan’s agriculture

Japan’s agricultural industry abounds with not only lies but also mysteries as shown below:

- Why is membership of the agricultural cooperatives growing even though the numbers of farmers and farm households are decreasing significantly?

- Why do agricultural policymakers, while stressing the need to improve food self-sufficiency and ensure food security, promote acreage reduction, which leads to lower rice production and fewer rice paddies?

- Why is the JA Bank prospering as a mega-bank even though Japan’s agriculture is declining?

- Why can the JA maintain significant political clout even though the farming population is falling?

Readers who want to unravel these mysteries and the fabrications discussed at the beginning of this article are encouraged to read two of my books: Kokumin no Tame no Shoku to No no Jugyo [Classes on food and agriculture for the public], 2022, Nikkei Publishing Inc.; and Nippon no Nogyo o Hakaishita nowa Dareka [Who destroyed Japan’s agriculture?], 2013, Kodansha. These books reveal truths that are inconvenient to the agricultural policy triangle.

Please also read my latest articles on the government’s moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act: “What is behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act?” dated November 9, 2022; and “‘Kaiaku’ no Ketsumatsu ga Sukeru Shokuryo Nogyo Noson Kihonho Minaoshi [Moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act will likely result in making the act worse]”, dated October 21, 2022.