Media Global Economy 2022.04.22

Will the Ukraine invasion bring about a food crisis in Japan? – Russia’s wheat export restrictions reveal the degree of its hardship

The complicated relationship between grain trade and the countries involved

The article was originally posted on RONZA on March 17th, 2022

The reality of Russia, the world’s largest exporter of wheat

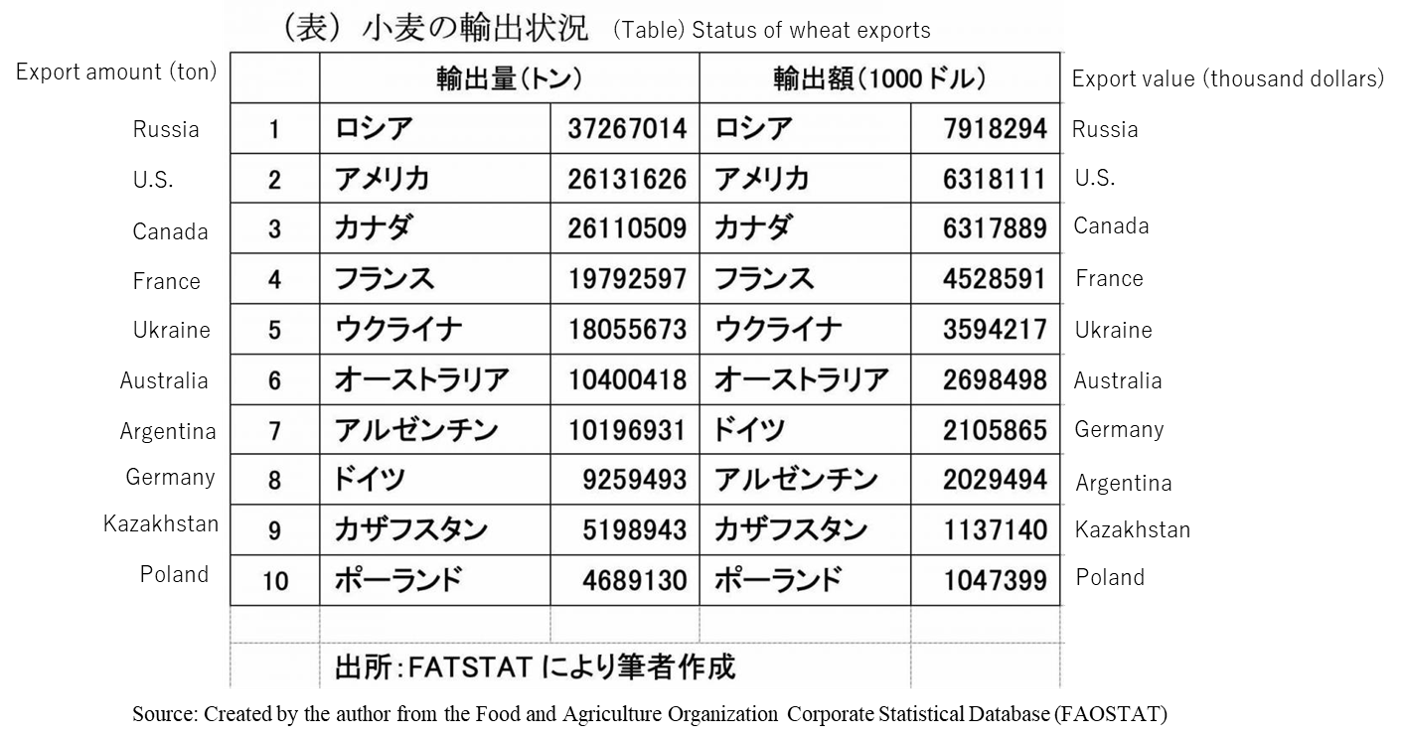

Russia and Ukraine are both major exporters of wheat (ranking first and fifth respectively by country). But EU countries as a whole export 61 million tons of wheat coming out on top, followed by Russia (37 million tons), U.S. (26 million tons), Canada (26 million tons), and Ukraine (18 million tons). Russia had at one time been the largest importer of wheat, as seen in the Soviet Union’s purchase of large amounts of grains that caused the 1973 food crisis, and has been an exporter of wheat only since the 2000s. For this reason, the two countries surrounding the Black Sea are called emerging wheat exporters. Moreover, the wheat produced by both countries is poorer in quality than that produced by the U.S. and other countries and are mainly exported to the Middle East. However, if their wheat exports were made difficult owing to logistical disruption caused by the war, the global supply of wheat would decrease, and the price level of wheat, including high-quality wheat, would rise.

Status of wheat exports

When crude oil prices rise, corn is used as a substitute

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the price of crude oil has been rising significantly. Ethanol is produced from corn as a substitute for gasoline. If crude oil prices rise and push up gasoline prices, the demand for ethanol as a substitute product also rises, leading to higher ethanol prices. As a result, the price of corn, from which ethanol is produced, rises and affects prices of other grains substituted for corn. Such a situation occurred in 2008. In this way, crude oil prices and grain prices are correlated. Ukraine is also the world’s fourth largest exporter of corn.

While exports of wheat and corn from Russia and Ukraine decrease on the supply side, there is growing demand for corn spilling over to other grains owing to the rise in crude oil prices. As a result, it is expected that prices of not only wheat but also corn, soybeans, and other agricultural products, of which Japan depends on imports, will rise. Although Japan purchases high-quality wheat from the U.S., Canada, and Australia through its state trading enterprise of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (MAFF), such prices are also expected to rise.

What effects will the Ukraine crisis have on Japanese household budgets?

Several private sector economists appearing on television have pointed out that higher wheat prices will affect household budgets since wheat is used as an ingredient of various food items, such as bread, ramen noodles, udon noodles, and spaghetti.

However, this is a mistake as I have pointed out in my article “Agricultural policies that are threatening food security: post-pandemic challenges, a weak yen, and a looming national crisis” (December 25, 2021). In 2008, when the international market price of wheat doubled and tripled and bread prices went up the same as this time, the Consumer Price Index for all items of food increased by only 2.6%. Also, when grain prices rose around 2012, the Consumer Price Index for food remained virtually unchanged.

The main reason is that the import value of wheat accounts for only 0.2% of Japan’s entire food-and-beverage spending. 90% of the expenses we pay for food and beverages are for processing, distribution, and dining out. The expenses paid for agricultural products are small, with only 2% spent on agricultural imports, including wheat.

Furthermore, as I mentioned above, with crude oil and grains (gasoline and ethanol), there is substitutability in consumption. If the price of beef goes up, we try to consume more pork. Wheat products such as bread and ramen noodles are not the only food we eat. If bread prices go up, rice consumption increases as a substitute for bread. In 2008, the consumption of rice, which had been declining, increased.

Goods and services have substitutability. Given that consumers earn a certain income, their decision to appropriately combine goods with consideration for the relative price of goods and services is the first step of microeconomics. “Substitutability” is an important keyword in studying consumption and demand for food.

Interestingly, in 2008 when rice consumption increased, there was a (novel) theory that the increase of the supply of furikake (Japanese rice condiment) shelved along with rice in supermarkets played a part in the increase, which was plausibly spread within MAFF and believed by quite a few MAFF officials. In fact, consumption of rice increased owing to its lower price compared with the rising prices of wheat products such as bread. The increased rice consumption had led to increased sales of furikake in supermarkets. It was the other way around. If the theory were correct, rice consumption could be easily increased by selling a lot more furikake. Unfortunately, most MAFF officials shape agricultural policies also without understanding economics.

MAFF is not serious about raising food self-sufficiency

There is a milk-drinking drive to promote consumption of surplus milk, but nearly all milk is produced by cows fed on imported corn, which means the self-sufficiency rate does not improve. Ingredients of bread and ramen noodles are almost 100% imported wheat. Even Sanuki udon noodles are made from wheat imported from Australia. The rise in wheat prices will lead to increased consumption of rice, grown almost 100% in Japan, and improve the self-sufficiency rate. The rise in prices of imported agricultural products is not bad news for those who want to raise the self-sufficiency rate.

But on March 11, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan gave the following answer to a reporter who asked whether rice would serve as a substitute for higher priced wheat:

“Our staple food is rice. So, I hope people will eat rice, but there are also many people engaged in the wheat industry. I cannot just promote eating rice at such a time when people suffer from increased wheat prices [omitted]. Well, rice is produced in Japan and is in surplus. In that sense, I would like to have people eat more rice, but when I think of those engaged in the bread industry and other various industries, I think I should refrain from promoting rice again under such severe situation.”

Improving the food self-sufficiency rate is only an excuse for MAFF to maintain agricultural protection. MAFF is not serious about raising food self-sufficiency.

Russia’s wheat export restrictions reveal the degree of its hardship

The Japanese mass media seem to be interested only in the effects of higher grain prices on Japan. But what effects will they have on Russia and Ukraine?

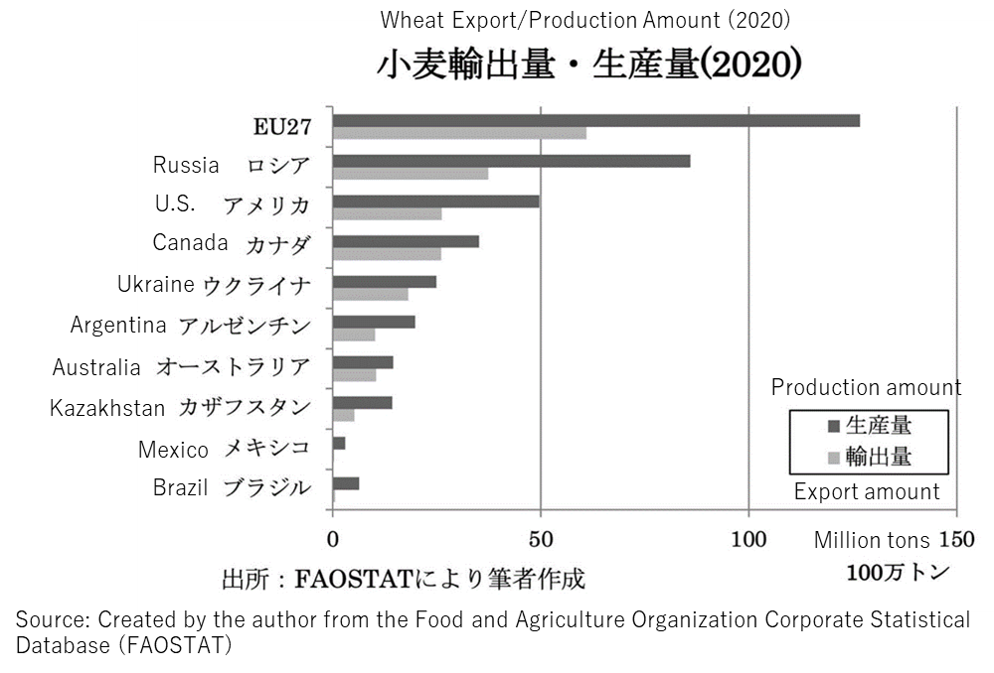

The following diagram shows the relation between production and export of wheat-producing countries. You may notice that exports account for a large percentage of production. The percentage for Russia is 43%, and for Ukraine reaches 73%. A similar situation applies for the U.S., Canada, and Australia, the countries from which Japan imports wheat.

Wheat export/production (2020)

Should these exporting countries become unable to export wheat, there would be an overflow of wheat in the country. Not only will the price of wheat decrease sharply, but wheat that cannot be stored in silos will also pile up in open farmyards.

In particular, the U.S., which suffered costly damage in the past, will not restrict its exports. In 1979, the U.S. banned the export of grains to the Soviet Union to impose sanctions for the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. However, the Soviet Union procured grains from Argentine and other countries, and American farmers lost the Soviet market. The U.S. hastily lifted the export ban the next year but saw a substantial slowdown in the agricultural industry and a wave of farm bankruptcies and abandonment.

When China substantially raised import tariffs on US soybeans in the ongoing US-China trade war, farmers in the Midwestern U.S., unable to export soybeans, had to rely on large amounts of government subsidies.

If exports are made unable or restricted, what the U.S. experienced will similarly happen to Russia and Ukraine.

However, in the past, when international grain prices soared, Russia restricted its exports. If exports were made freely, lower-priced grains of Russia would be supplied to the global market, resulting in decreased domestic supply of grains and increase in grain prices to the same level as that of the international prices. If such were the case, unlike high-income countries such as the U.S. and Canada, in lower-income countries like Russia, where a considerable part of the income is spent on food, people would not be able to stand the increase in grain prices. Through export restrictions, domestic grain prices can be kept lower than international prices.

On March 14, the Russian government decided to temporarily ban exports of wheat and other grains to neighboring countries of Belarus and Kazakhstan. Owing to a sharp drop in the value of the ruble, daily commodity prices have been increasing. By keeping down the price of self-sufficient wheat and other grains, Russia seeks to lighten the burden on people’s living expenses as much as possible. For Russia, Belarus is an important ally with which joint military exercises had been conducted until just before the Ukraine invasion and so much an ally that Belarus has been reportedly asked to dispatch troops. The fact that Russia has to restrict its exports to such an ally like Belarus indicates that Russian people’s living expenses are being put under considerably severe pressure.