Media Global Economy 2022.01.31

Agricultural policies that are threatening food security: post-pandemic challenges, a weak yen, and a looming national crisis

A downturn in people’s lives and agriculture now becoming a reality

The article was originally posted on RONZA on December 25th, 2021

There are concerns about the impact on household budgets of rising prices of agricultural products imported into Japan, especially grains such as wheat, soybeans, and corn (oilseed-type soybeans are also treated as a grain in this article). Since wheat is used to make bread, udon noodles, ramen noodles, spaghetti, etc., while soybeans are used to make cooking oil and margarine, and corn, to feed livestock that produce milk, meat and eggs, a rise in the prices of these commodities would lead to a rise in the prices of final food products.

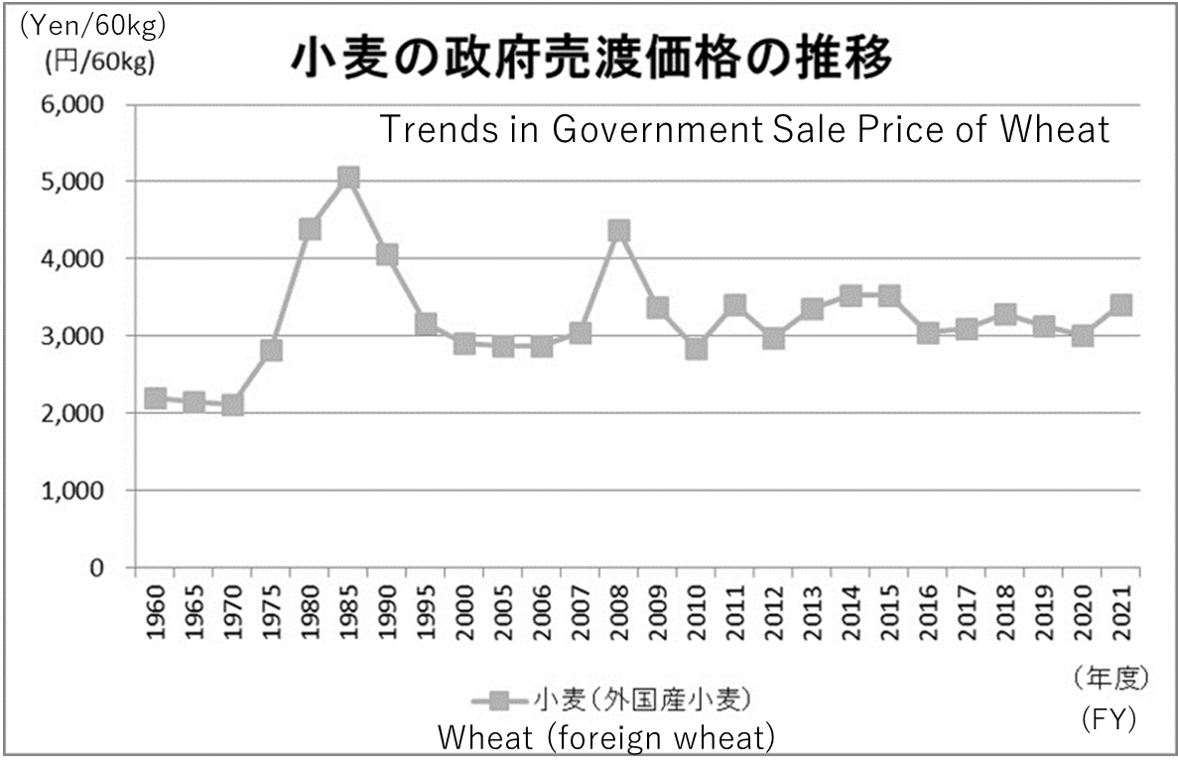

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) imports wheat from the U.S. and other countries, collects a surcharge to fund domestic wheat protection, and then sells the imported wheat to flour-milling companies. The MAFF raised the price of imported wheat by 19% in October, the first increase since a 30% hike in 2008. If the price increase is passed on to prices of final products, the price of a loaf of bread (400 grams) will increase by 2.3 yen, and that of weak flour (one kilogram) for household use, by about 14.1 yen.

Crude oil price recovery boosts grain prices

There are two factors that contribute to the rise in the price of imported grains. One is the rise in international prices, and the other, the depreciation of the yen.

The rise in international prices is caused by global supply and demand trends for grains. On the demand side, the recovery of Chinese import demand has been cited as the cause. Pork production had plunged in China since 2018 dented by the African swine fever epidemic. The production has been recovering and rebounding since last year, leading to a growing demand for corn and soybeans to feed pigs. China has a major impact on the international soybean prices, as it accounts for 60% of the world’s soybean imports. On the supply side, meanwhile, harvests in the Americas have declined owing to hot and dry weather. If demand increases and supply decreases, prices will rise.

Although it has not been widely reported, there is a non-agricultural factor that contributes to the rise in the price of imported grains, i.e., the recovery in crude oil prices, which plummeted last year on account of the COVID-19 disaster. Perhaps surprisingly, crude oil prices and grain prices are correlated. Ethanol, made from corn and sugar cane, is a substitute for gasoline. Brazil uses ethanol made from sugar cane, and the U.S. mixes gasoline with ethanol made from corn to run their cars. In the U.S., the largest producer of corn, the use of corn for ethanol has expanded to the same level as that for feedstuff, with the use for these two purposes now accounting for more than 70% of corn use.

In tandem with the increasing crude oil price, the demand for ethanol, a substitute product, will grow, raising the prices of corn and sugar. When this happens, the prices of soybeans and wheat, which are substitutes for corn, will also rise. This is how the prices of grains have come to be linked to the price of crude oil. Consumers around the world will begin to suffer the negative effects of rising crude oil (energy) and food prices at the same time.

A weaker yen means that you will pay more yen to buy a dollar’s worth of goods, so even if international prices remain the same, the price of imported goods will rise. From the consumer’s point of view, a strong yen is better than a weak one. Traveling abroad when the yen is strong, we strongly feel the benefits of yen appreciation. When the EU introduced the euro, some Germans were against it, because they did not want the strong mark to disappear. They feared that by switching the mark to the euro, they would lose purchasing power. In order to combat inflation, the U.S. has shifted its monetary policy and begun to phase out quantitative easing. If interest rates in the U.S. eventually rise, the yen will weaken further.

As for wheat, current prices are lower than in 2008 as shown in the chart below. Wheat prices have been stable since 2010.

Food prices are not rising as fast as grain prices

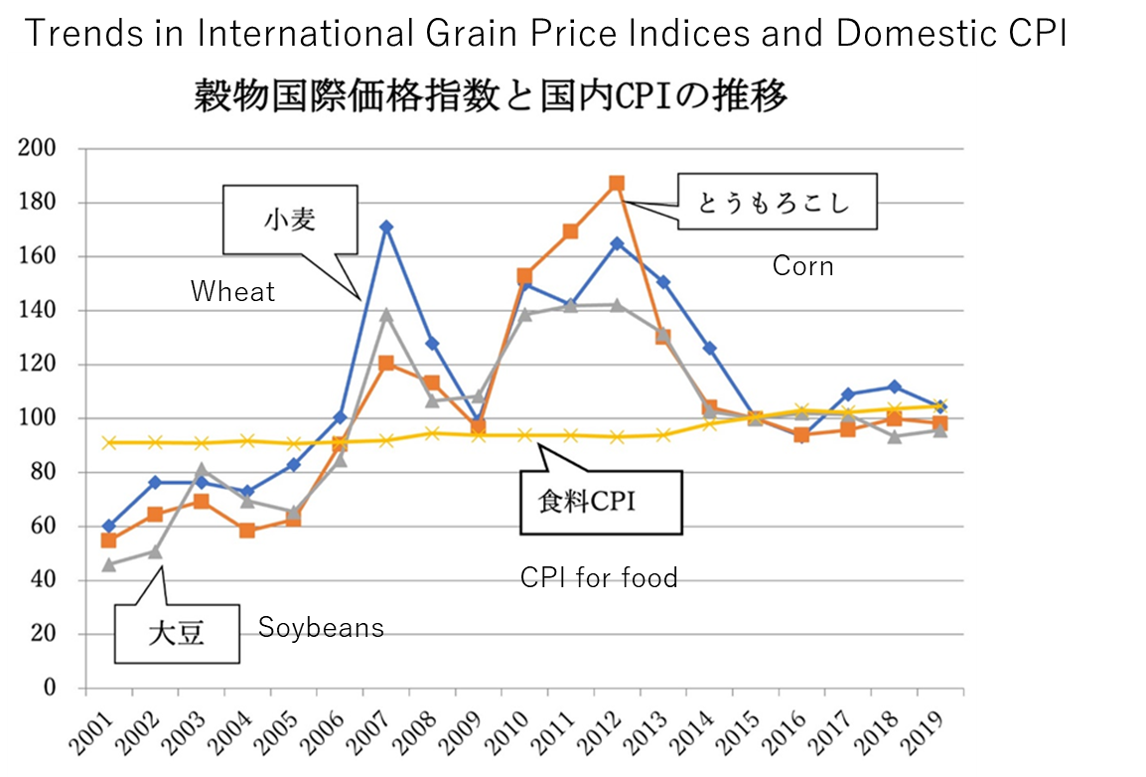

In 2008, the year of the global food crisis, the international price of grains tripled, but the Consumer Price Index for food in Japan rose only 2.6%.

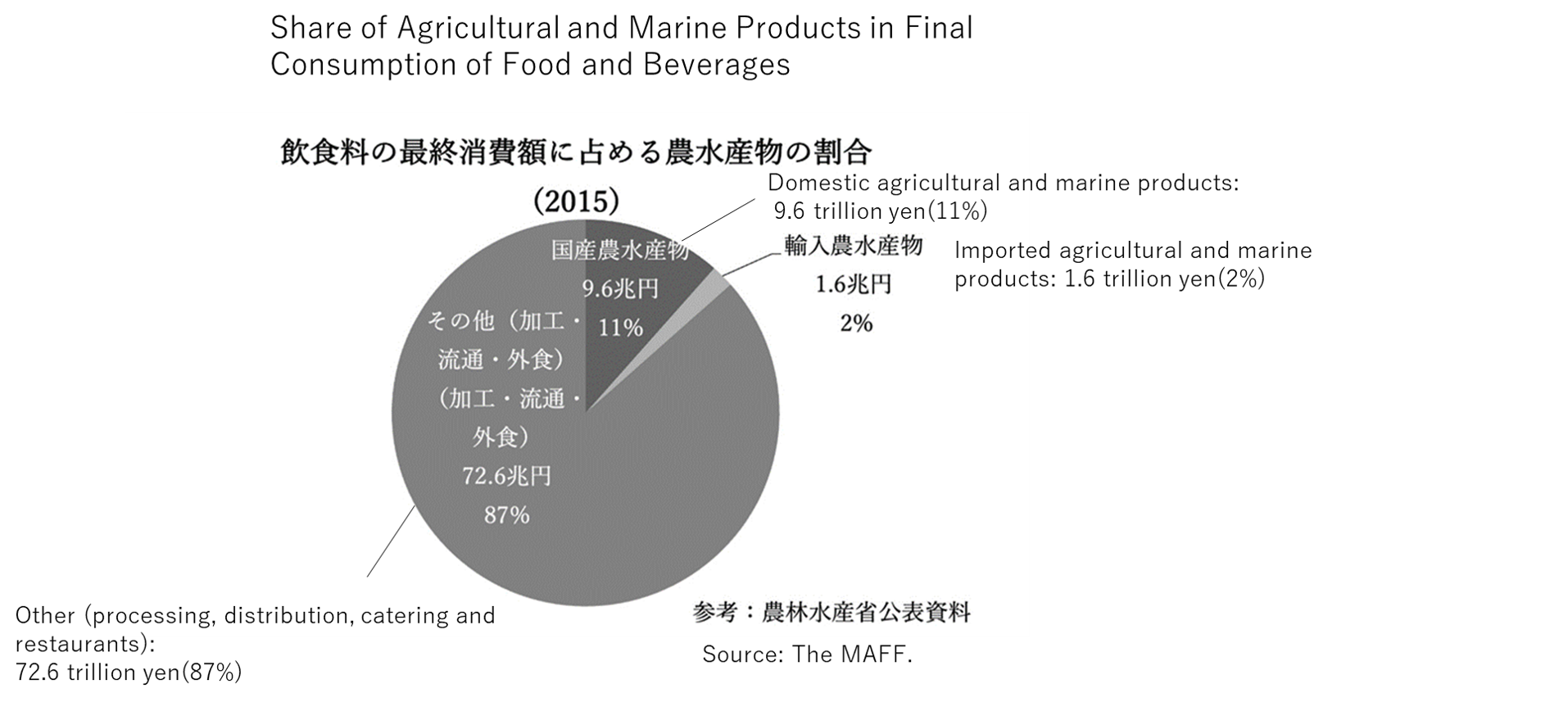

This is because imported agricultural and marine products account for only about 2% of the final consumption of food and beverages in Japan. Even domestic agricultural and marine products account for only 11%, with processing, distribution, and dining out making up 87% (2015). Even if the price of grain, which is part of imported agricultural and marine products, rises, it will not have a significant impact on final consumption. This pattern of consumption is common in developed countries. When we buy food, we are not paying much for agricultural products, but for processing, distribution, and dining out.

A food crisis like the one that occurred in the Philippines in 2008 will never occur in developed countries. No one in Japan should have felt a food crisis in 2008. Although international prices also rose during the 2011-2013 period, there was no disruption.

A huge burden imposed on consumers in the name of agricultural protection

However, Japanese consumers are already bearing a huge burden.

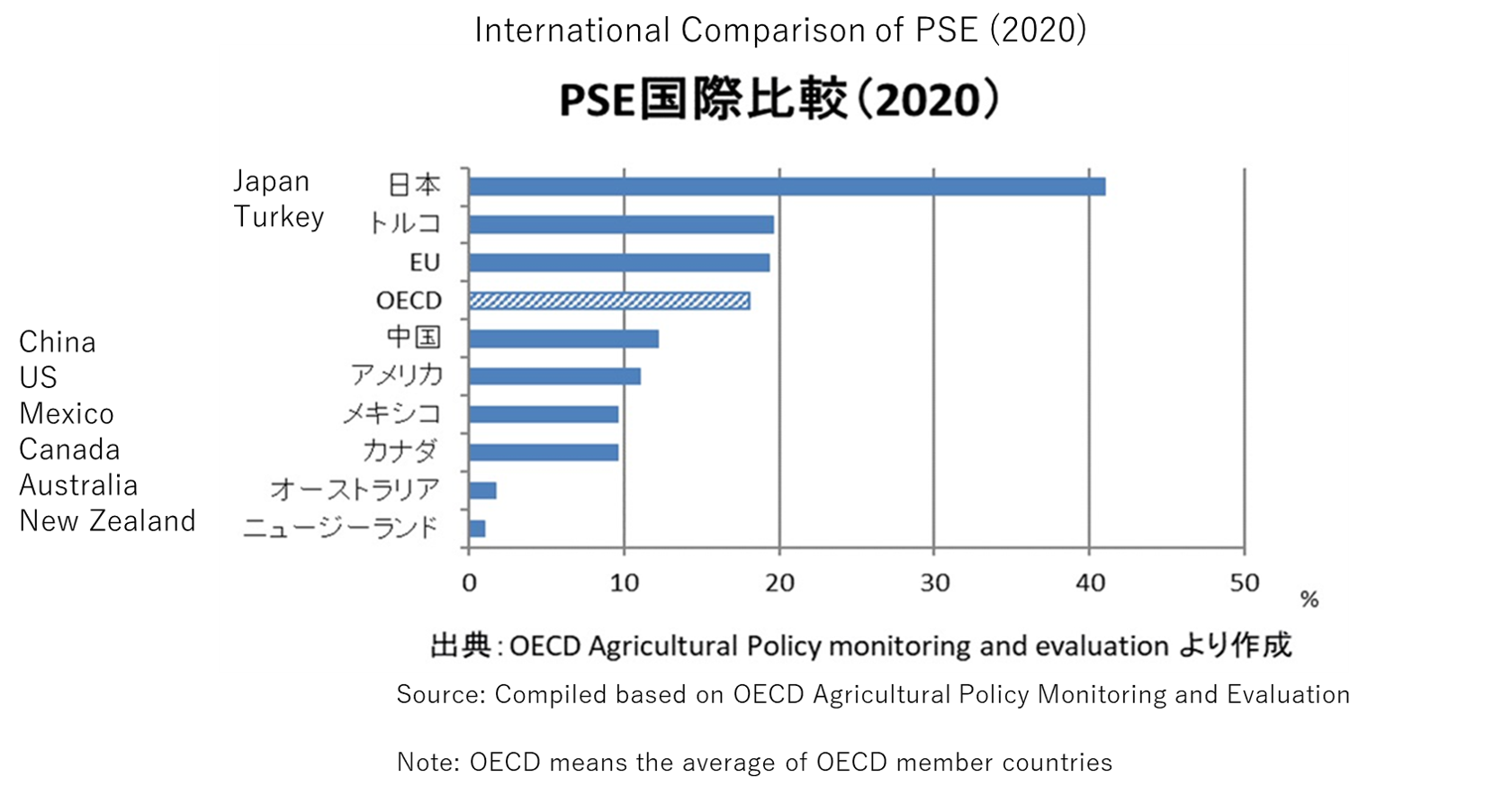

The Producer Support Estimate (PSE), an indicator of agricultural protection developed by the OECD, is the sum of the taxpayer burden, which is the financial burden to maintain farmers’ income, and the consumer burden, which is the difference between the domestic price and the international price (the gap between prices inside and outside) multiplied by the domestic production volume (the amount of income transferred to farmers by consumers paying high domestic prices to farmers instead of low international prices). (PSE = financial burden + gap between prices inside and outside x production volume)

However, as in the case of wheat and beef, consumers also bear high tariffs on imported agricultural products in order to maintain high prices for domestic agricultural products, and the amount paid by domestic consumers for agricultural protection exceeds the PSE, which is merely the gap between prices inside and outside multiplied by domestic production volume.

The share of agricultural protection PSE as a percentage of the amount of money received by farmers (hereinafter “%PSE”) is high in Japan at 40.9% as of 2020, compared to 11.0% in the U.S. and 19.3% in the EU. This means that in Japan, 40% of the income of farmers is from agricultural protection. Furthermore, compared to 1999, when the level of protection was high in each country, the U.S. and the EU saw their %PSE drop by about 50% from 25.5% and 38.5%, respectively, while Japan’s %PSE decreased only by 30% from 59.9%.

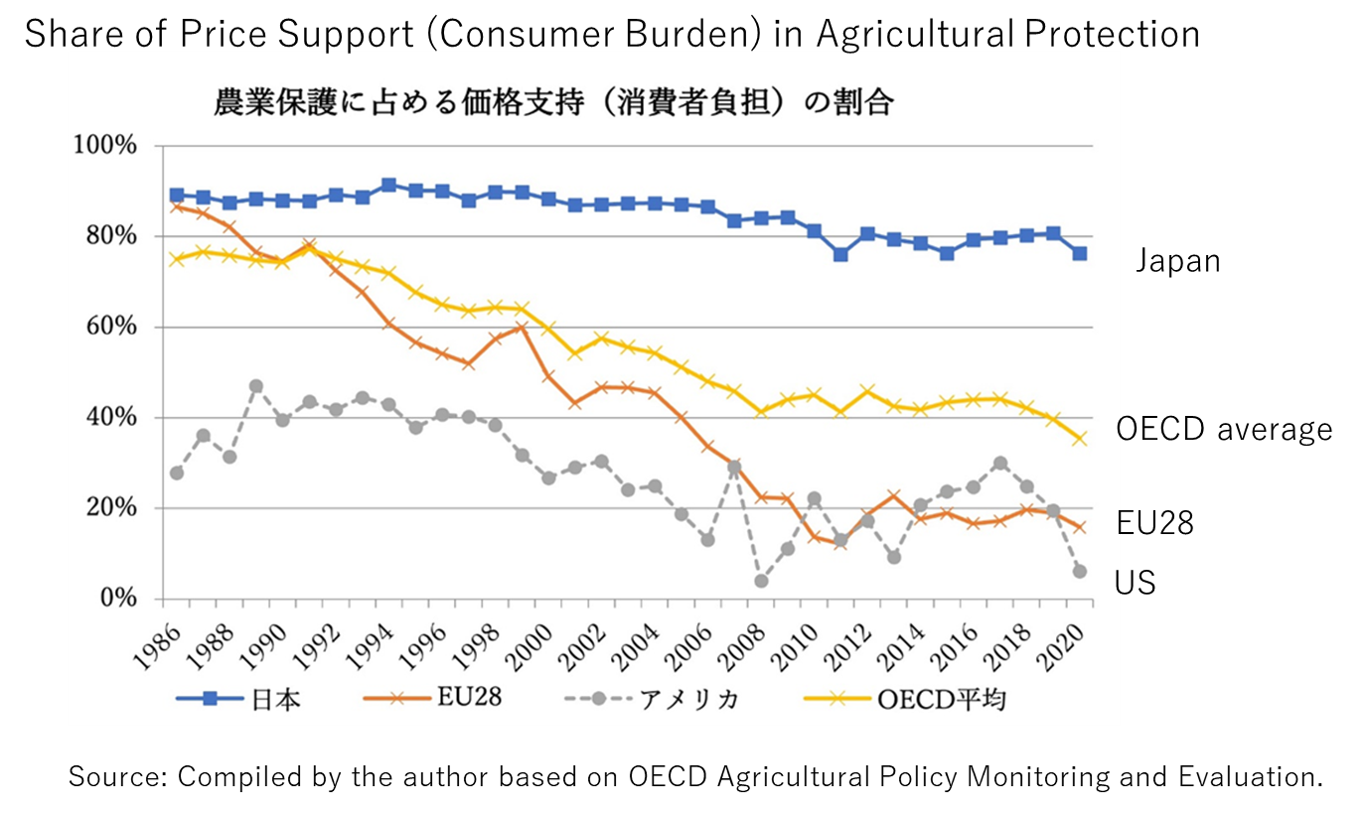

In addition, Japan’s agricultural protection is characterized by an overwhelmingly high percentage of consumer burden. A look at the breakdown of PSE in each country finds that the percentage of agricultural protection that is borne by consumers was 6% in the U.S., 16% in the EU, and 76% in Japan in 2020, compared to 37% in the U.S., 86% in the EU, and 90% in Japan in 1986-1988, the base period for the reduction of farm subsidies determined by the Uruguay Round negotiations. While the figures for the EU, which has shifted from price supports to direct payments, fell sharply, Japan’s agricultural protection remains centered on price supports. With domestic prices greatly exceeding international prices, Japan is forced to impose high tariffs on imported products.

Regressive agricultural policies that continue to increase the consumer burden

Politicians described the TPP negotiations as a “battle for the national interest.” That national interest was to maintain protective tariffs on agricultural products. What the tariffs protect is the high prices of domestic agricultural products, i.e., food. It is the farmers who are protected by the high prices, and it is the consumers who shoulder the burden.

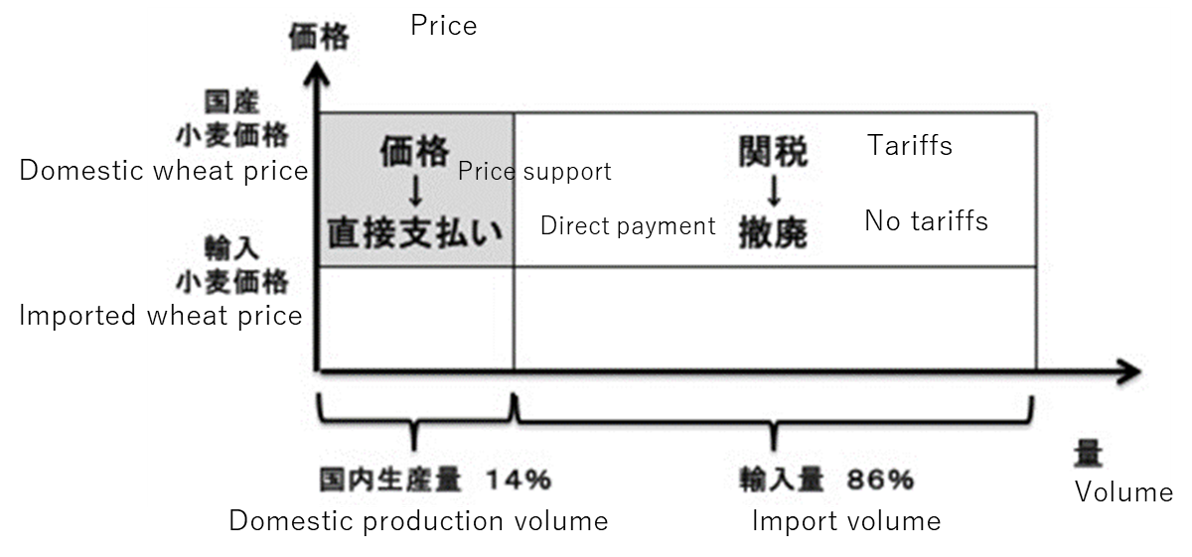

For example, in order to maintain the high price of domestic wheat, which accounts for only 14% of the total wheat consumed, a tariff (or more accurately, a surcharge collected by the MAFF) is imposed on foreign wheat, which makes up 86%, thereby forcing consumers to buy expensive bread and udon noodles. A policy change to make up the difference between domestic and international prices of agricultural products through direct fiscal payments would have the great advantage of freeing consumers from the consumer burden associated with not only domestic but also foreign agricultural products. It could provide the same protection to agriculture but reduce the burden on domestic consumers.

Rice policy has far more problems. In the case of normal policies, such as healthcare policy, people should be able to receive goods and services at lower prices if they bear the financial burden as taxpayers. Under the current rice policy, on the other hand, the government pays 400 billion yen in subsidies to farmers every year to cut rice production (i.e., “acreage reduction”), which results in a much higher price for rice than can be realized in the market, thus increasing the burden on consumers. In addition, the government has implemented the most regressive policy for rice, the staple food, of all food and beverage products. This has been made possible by the existence of tariffs (as I have mentioned again and again in Ronza, the abolition of acreage reduction is fake news created by the Abe administration).

Also under the livestock policy, the government has invested huge financial resources, amounting to as much as 3 trillion yen, since the liberalization of imported beef in 1990, but the price of livestock products purchased by the public has risen. Beef prices are at historically high levels, despite the tariff reductions resulting from the TPP. The price of Wagyu calves and carcasses has almost doubled in the past 20 years. The price of raw milk sold by dairy farmers has also risen almost steadily from 79.2 yen per kilogram in FY2007 to 105.5 yen per kilogram in FY2020. When the price of raw milk rises, the price of milk and dairy products also rises.

The OECD estimates that the burden on Japanese consumers of paying higher prices than international prices is nearly 4 trillion yen. This is almost the same amount as the additional burden placed on the Japanese people by the increase in the consumption tax from 8% to 10%. If we eliminate the regressive nature of the agricultural policies, it will offset the increase in the burden on consumers caused by the consumption tax hike.

When raising the consumption tax, some politicians expressed concern that the increase in food prices arising from the consumption tax hike would place a greater burden on the poor, who spend a larger proportion of their income on food, and consequently, a reduced tax rate has been adopted for food. But how effective has this been? Or how serious those politicians are? Let us examine the government’s sale price of imported wheat in April this year as an example. The import price is 38 yen, the surcharge collected by the MAFF is 11 yen, and the 8% consumption tax is 4 yen, which means the effect of reducing the 10% tax rate to 8% is only one yen. Put simply, the Diet members want to say that they have eliminated the regressive nature of the agricultural policies by reducing the consumption tax by only one yen, while forcing consumers to pay as much as 11 yen in surcharge. Do they think we are stupid?

Worst-case scenario: possible disruption of grain imports

Currently, there is a shortage of container ships due to the recovery and rebound of trade volume after the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic subsided and on account of the shortage of port workers stemming from the pandemic. Agricultural production has been hit by the difficulty in importing grass that dairy farmers use as feed. The unit price of grass is low for a given volume. Compared to other commodities, it is like carrying air, so the import of grass has received low priority.

Even if the price of grain rises, it is unlikely that Japan, a high-income country, will become unable to afford it. However, a food crisis could occur when imports become impossible owing to logistical disruptions as in the present case of grass imports. This time, although the import of grass was affected, the shortage of containers did not disrupt the import of wheat and other grains. Nevertheless, if Japan’s sea lanes are disrupted owing to an emergency in the Taiwan Strait and other reasons, the risk of not being able to import food will increase.

We are on the verge of a crisis; now is the time to abandon the agricultural policies that are destroying the nation

That being said, 5 million tons of rice is being reduced with the aim of keeping the price of rice high under the acreage reduction policy, whereas 8 million tons of wheat is being imported. The MAFF has set the appropriate rice production volume for next year at 6.75 million tons and presented it to the Agricultural Cooperatives and others. It is less than half the 14.26 million tons produced in 1967 and far less than the 7.83 million tons in 1993 when Japan experienced a historically poor harvest, an event called the “Rice Riots of the Heisei Era.” The rice acreage reduction policy has prohibited development of a new rice variety aimed at yield improvement per unit area, and the amount of farmland (paddy fields) essential for food security has been reduced from 3.5 million tons to 2.5 million tons.

The MAFF does not seem to care about the drop in the production of rice, a staple food, below the 7-million-ton level. Shockingly, both the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA) and the lawmakers of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) affiliated with the JA insist that rice production should be cut further in order to keep rice prices high.

It is not the U.S. or Australia, which is pushing for liberalization of agricultural trade, that is destroying Japan’s agriculture and putting Japan’s food security in jeopardy. Those who are destroying Japan’s agriculture are the JA, which is demanding increased acreage reduction to keep the price of rice high; the lawmakers of the LDP affiliated with the JA who do not want to lose their organized JA votes to their opponents in the election; and the MAFF, which is forced to listen to the JA and the lawmakers affiliated with the JA in order to maintain its organization and budget.