Media Global Economy 2020.02.27

Farm households no longer vulnerable: Huge windfall profits reaped from the conversion of agricultural land to other uses, escalating medical costs caused by Japanese-style livestock farming -- no need to protect a strong agriculture

People do not know about agriculture and farming communities

Most Japanese people believe that farm households are poor and vulnerable and consider that they deserve protection by tariffs and subsidies.

Before the post-war economy recovered, rural areas were more affluent and capable of supporting the population compared to urban areas such as Tokyo. After economic recovery in the third decade of the Showa era (1955-1965), demand expanded for labor at factories in larger cities, which led to a major migration of the population from rural areas to big cities such as Tokyo and Osaka. The explosive popularity of songs reminiscing about the hometown in this period, such as "Ringo Mura Kara (From the Apple Village)," indicates the influx of people from rural areas into larger cities.

However, as I pointed out in the article "Unknown aspects of Japan's farming communities: the average annual income for pig farmers is 20 million yen!" (December 27, 2019), Japanese agriculture and farming communities have undergone dramatic changes since the fourth decade of the Showa era. People who migrated to big cities, such as Tokyo, in the third decade of the Showa era know only the agriculture and farming communities before changes took place. Before the changes, most farm households in farming communities were poor and subject to hard labor. Rice planting was backbreaking manual labor before rice planters became widely used. This image has been described even in school textbooks and solidified by TV dramas such as "Oshin."

A similar phenomenon is seen also in local areas. People migrated to local cities such as prefectural capitals, so most of them do not know about the actual conditions of agriculture and farming communities.

Farm households accustomed to being considered vulnerable

Reporters of national and local newspapers that provide news to the public are usually exposed to only the political comments from agricultural groups, such as "agriculture will be destroyed if tariffs are eliminated." There is no way that agricultural groups, whose business is political activities, would make other claims on trade liberalization negotiations.

Reporters might visit farm households, but since they themselves have an image that farm households are vulnerable, they are convinced by farmers' superficial comments such as "painful and tough" and do not seek the hidden details or honest and real opinions.

Farmers have become all too used to providing such answers.

If tariffs are eliminated, prices of agricultural products may fall to a certain degree and income decrease. However, even if farmers' income were to decrease a little, it would still be higher than that of workers engaged in other industries.

Nevertheless, it is better not to have one's income decreased. Farm households would not want to see their income of 30 million yen (272 thousand dollars) reduced to 25 million yen(227 thousand dollars). When asked by reporters, "How would it be if tariffs were eliminated?" no farmer would answer, "It'll be okay without tariffs."

There is no other industry that has been protected and supported by the government as much as agriculture has.

However, being regarded vulnerable for too long a time, the farmers themselves have become accustomed to being protected by tariffs and subsidies and feel no shame about it. On the contrary, they have come to take it for granted.

Farm households are no longer poor

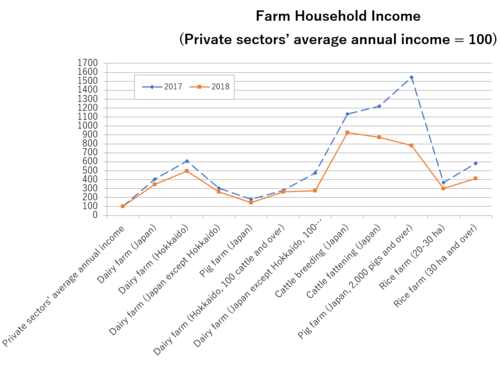

The following graph shows a comparison of farm household income with the private sectors' average annual income (salaried workers' income) with the latter based as 100.

Since income fluctuates by year, the graph shows data for the two years of 2017 and 2018 (preliminary figures for farm household income). The average annual income of private-sector employees was 4.32 million yen (39 thousand dollars)in 2017 and 4.41 million yen (40 thousand dollars)i in 2018.

Income of farm households not only consists of income from agriculture but also includes other income such as from working at factories (non-farming income) and pension income. However, in livestock farming, since most households are full-time farmers, their non-farming income and pension income are not so high, except for the cattle-breeding and cattle-fattening sectors. Agricultural income is calculated by subtracting total costs, including employees' salary ("hired farm labor"), from agricultural gross receipts, including sales of agricultural products. (Source: Report of Statistical Survey on Farm Management and Economy (statistics by type of farmer) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) for income of farm households; Statistical Survey of Actual Status for Salary in the Private Sector in 2018 of the National Tax Agency (NTA) for average annual income of private-sector employees)

Income of cattle-breeding households raising calves is comparatively low, due mostly to small-scale farms managed by elderly pensioners. Even so, their income exceeds the average annual income of private-sector employees.

Household income of the given farming types other than cattle breeding is more than twice the average annual income of private-sector employees. In large-scale dairy and pig farming, income is eight to nine times the average annual income of private-sector employees even in 2018 when income decreased.

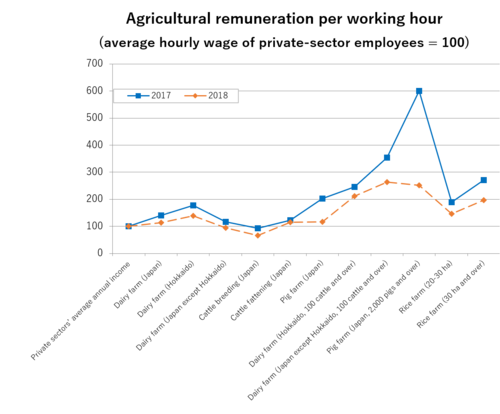

The following graph compares the per-capita agricultural income (income and earnings) of farm households per hour with the average hourly wage of private-sector employees, with the latter based as 100. Non-farming income and pension income are not included.

The graph shows data for the two years of 2017 and 2018 (preliminary figures for agriculture). The average hourly wage of private-sector employees was 2,133 yen (19 dollars) in 2017 and 2,205 (20 dollars) in 2018. Except cattle breeding and the 2018 dairy sector for all prefectures except Hokkaido, the average hourly farm income exceeded the average hourly wage of private-sector employees. Here again, the average hourly farm income of large-scale dairy and pig farmers was more than twice the average hourly wage of private-sector employees.

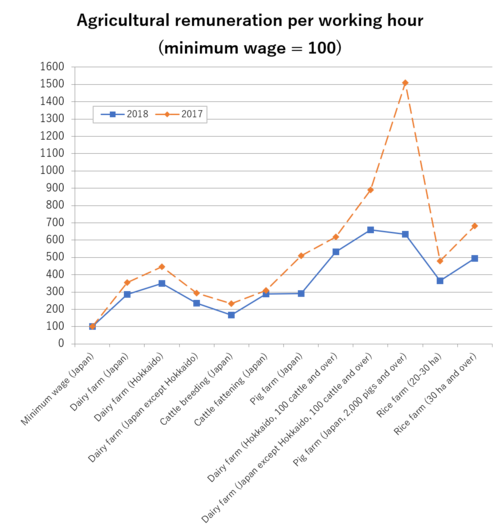

If the average hourly farm income should fall below the minimum wage, it might be necessary to take special measures to protect agriculture. To verify this, the following graph compares the agricultural hourly remuneration (income) with the minimum wage (Japan) with the latter based as 100.

Minimum wage (Japan) was 848 yen (7.7 dollars) in 2017 and 874 yen (7.9 dollars) in 2018 (the minimum wage in farming prefectures of the Tohoku and Kyushu regions is lower at around 750 yen (6.8 dollars)). However, even the cattle-breeding sector with the least remuneration earns almost twice the minimum wage.

Farm households, especially livestock farming households are not poor by any means. On the contrary, they have more income than those engaged in other industries. A strange system by which the poor public provides financial support to the rich farmers has existed.

Are farm households vulnerable?

Now, let us see whether farmers are vulnerable.

When farmers and agricultural groups lobby the government for agricultural protection, they often claim that farming is harsh.

But any occupation accompanies physical and mental strain, and agriculture alone is not exceptionally harsh. In particular, mechanization has rapidly progressed in farming and significantly reduced the physical burden of farmers. Today, there are even air-conditioned tractors and milking robots.

I have experience of farm work before such progress was made in mechanization but did not find the work so tiring or trying. Salaried employees working in the cities have a three-hour commute on crowded trains each day, suffer from chronic overtime work and strained personal relationships with superiors and peers, including power harassment, and must bow before clients even when they make unreasonable demands outside the office. I think their work is considerably stressful physically and mentally. Isn't it?

Agriculture is said to be difficult because it deals with living things in the form of animals and plants. Hospital doctors and nurses also take care of the lives of human beings that are also living things. They are summoned even at midnight if the patient's condition worsens. Would it be possible for agriculture to receive empathy for claiming it were the only tough occupation?

Huge profits reaped from conversion of agricultural land to other uses

That is not all. Farm households may consider themselves vulnerable and victimized, left behind social prosperity, but there are cases in which farm households have become the victimizer without their knowing.

One example is the shutting down of stores at former local shopping streets in local cities. The direct cause of this shutting down is the emergence of large-scale suburban retail stores. It is the farm households that provided the land for the stores.

One hectare of agricultural land is not large for farming, but 10,000 square meters or about 3,000 tsubo of commercial land would be more than large enough for retail stores. When I was a college student in the mid-1970s, I saw more agricultural land along the Sanyo Main Line converted to other uses every time I returned home from Tokyo. And customers gradually disappeared from my hometown shopping streets.

Furthermore, in one of Okayama Prefecture's famous shopping streets, Omotecho Shopping Street, which was once crowded with shoppers, only bookstores and coffee shops are now open. Most stores closed the shutters and went out of business. Farm households and agricultural groups might demand compensation from the government, but store owners who lost their jobs commendably do not only refrain from shouting about it but just patiently endure the hardships. Which of the two is more unfortunate, farm households that suffer only a small decrease in the price of agricultural products with the elimination of tariffs or store owners who have been forced to close their business?

Essentially, conversion of agricultural land to other uses was supposed to be strictly limited by the Agricultural Land Act. Land reform was carried out to have agricultural land used as agricultural land, not to have tenant farmers convert agricultural land to residential land and gain huge profits through land conversions.

The area of agricultural land reached 6.09 million hectares in 1961 but has since declined to 4.4 million hectares today. On the surface about 1.7 million hectares of agricultural land have been lost. But taking into consideration that an additional 1.1 million hectares of agricultural land have been developed by public works projects, etc. during the same period, in actuality, 2.8 million hectares of agricultural land have been lost. This corresponds to two-thirds of the current area of agricultural land. Half of it is due to abandonment of cultivation, while the other half is due to the conversion of land for non-agricultural use such as residential and commercial use.

Agricultural groups claim that business corporations that acquire agricultural land convert the land to other uses at some future date. However, it is none other than the agricultural industry that has abandoned agricultural resources that are vital for food security through land conversions, etc.

Farm households deposit the profits they have gained through the conversion of agricultural land in their accounts at Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA). This has contributed significantly to the growth of the JA Bank into a megabank with Japan's second largest deposits. If business corporations sell the land to convert to other uses, they would not deposit the proceeds in the JA Bank. When I was a MAFF official, I was engaged in the business of conversions of agricultural land to other uses for a while, but I have no recollection of JA being serious in securing agricultural land resources.

Conversely, it was the chambers of commerce and industry, consisting of small- and medium-sized companies, that requested strict and proper operation of the agricultural land conversion regulations. This was because they wanted to prevent the shutting down of shopping streets by having the government restrict its main cause, the conversion of agricultural land to other uses.

In this regard, however, unlike the JA, the chambers of commerce and industry regrettably were not equipped with the political power to have their request fulfilled.

Pressure on foreign trainees

Agriculture, cited for its labor shortage, has been taking advantage of the Technical Intern Training Program for Foreigners from an early stage.

About 7 to 8 percent of foreign trainees in Japan receive on-the-job training in the agricultural industry. Considering that agriculture accounts for 1 percent of GDP, one can notice the abundance of foreign trainees in the agricultural industry.

The original purpose of the training program was to provide training, technical skills and technology experience to foreign trainees so that they may contribute to the development of their home countries, but many farm households consider the program as a means of securing cheap labor.

Regarding this Technical Intern Training Program for Foreigners, farm households are noted for many cases of malpractice such as not even paying the minimum wage, making trainees work unjustly during busy farming seasons, taking passports from trainees to prevent them leaving, etc. There are about 200 cases of malpractice discovered every year. By industry, the agriculture and fisheries sectors have the greatest number, accounting for 30 percent of all cases.

Foreign trainees who cannot withstand such treatment abscond. The rate of absconding in agriculture is 17 percent, the second highest after the construction industry and nearly twice the percentage of other industries.

It may be just some farm households that are committing these acts, but if any farm household does not pay even the minimum wage to foreign trainees while they themselves earn remuneration of more than twice the minimum wage, it is an act of discrimination and exploitation.

Japanese-style livestock farming is a factor behind escalating medical costsIn another respect, livestock farming has become a victimizer.

In the article "Unknown aspects of Japan's farming communities: the average annual income for pig farmers is 20 million yen!" I pointed out that Japan's livestock fed with corn from the US has caused the nitrogen content of the excreta to build up in large quantities across Japan.

This type of livestock farming may be a remote cause of escalating medical costs. Recently, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) did a special feature on the roles of omega-3 and -6 fatty acids twice: in its Asaichi program on January 8 and NHK Special program on January 12.

Omega-3 fatty acid, found in fatty fish and nuts, has the function of turning the blood in a smooth state. In contrast, omega-6 fatty acid, found in beef, pork, butter, soybean oil, corn oil, etc., has the important function of making white blood cells attack virus and pathogens, but its excessive intake leads to attacks on the very body itself, accelerating arteriosclerosis and causing myocardial infarction and cerebral infarction. While omega-3 fatty acid plays a role in inhibiting these attacks, if the ratio of omega-3 and -6 fatty acids exceeds 1:2, omega-6 fatty acid goes out of control. As Japanese people have adopted a Western-style diet that consumes a lot of livestock products, this ratio in Japanese people has changed from 1:6 to 1:10.

In wild animals, the ratio is 1:2. The ratio is also 1:2 in cattle fed and fattened on grass. However, the ratio of cattle fed on grains such as corn rises to 1:8 to 1:10. Consumption of domestic grain-fed beef will cause arteriosclerosis that leads to myocardial infarction and cerebral infarction. Australian lean beef excels in health aspects. This means that Japanese people bear higher prices from tariffs and the burden of subsidized projects as taxpayers in support of high-income livestock farmers. As a result, they are forced to bear the burden of higher medical costs.

Japanese livestock farming that is dependent on imported grains has a negative effect on the environment and on people's health. In economics, this is called negative externalities. In this case, the policy prescription prepared in economics would be imposing regulations and taxes to curb and decrease the activities that have such effects, not protecting or subsidizing them.

Under the Abe administration, assertive phrases such as "strong agriculture" and "aggressive agriculture" have been bandied about for several years.

However, if Japan's agriculture is strong enough to penetrate other countries' markets, why is it necessary to protect or support it? Those who need protection are not called "the strong".

Japan should not have made subsidies and promotions for the livestock industry as a measure against the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement and Japan-US trade agreement. Not only that, the content of the measures is filled with inconsistencies that undermine the interests of the country and people of Japan.

In my next article, I would like to point out the issues of the liberalization measures.