Media Global Economy 2020.02.12

Unknown aspects of Japan's farming communities (I): the average annual income for pig farmers is 20 million yen($182 thousand)! No "Oshin" in farming communities in Japan today; no need for income compensation with taxpayers' money

Public funds have been used for farmers who are not affected

To date, the Japanese government has spent some 300 billion yen (US$ 2.7 billion) a year for measures designed to compensate farmers who are ostensibly affected by the Trans-Pacific Partnership, to which the US was originally a party. The Japanese government insists that, in the latest Japan-US talks over a free trade agreement (FTA), it limited its concessions on farm tariff cuts within the levels agreed on in the TPP. If that is the case, no additional measures are necessary. Yet the government plans to implement further steps in addition to the measures already taken following the TPP negotiation process.

To begin with, of all the products said to be sensitive to Japan's agriculture, beef and pork are virtually the only items that were made subject to tariff reduction in the TPP among other FTAs. (The beef tariff will be reduced from 38.5% to 9% over a period of 16 years.) Will this affect Japanese farmers?

It would not have a significant impact--this is the position that the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) had been taking. Nevertheless, compensatory measures have been taken. On top of that, these measures have cost more than 200 billion yen (US$ 1.8 billion), the maximum level of production loss that the MAFF estimates.

Eight years ago, because the beef tariff was 38.5%, foreign beef worth 100 yen per 100 grams was sold for 138.5 yen on the domestic market. (A tariff of 9% would mean that the price would fall to 109 yen.) Yet the yen has weakened by about 35% since then. The beef worth 100 yen per 100 grams back then is imported to Japan for 135 yen before tariff. With a 9% tariff, the product is sold in Japan for a unit price of 147 yen. A comparison with the situation eight years ago shows that the level of protection for Japanese farmers is higher due to the weaker yen despite the lower tariff.

As for pork, the reduction or elimination of tariffs would not cause any harm because a special tariff arrangement is in place to ensure that the import price stays the same even in the case of a lower tariff. This arrangement is too complex to be detailed here. (See my book titled "TPP Will Make Japanese Agriculture Strong" [in Japanese] for detail.) It is nevertheless something MAFF bragged about as a positive outcome of the TPP negotiations.

Japan's livestock farming is thriving

Are Japanese farmers really being affected?

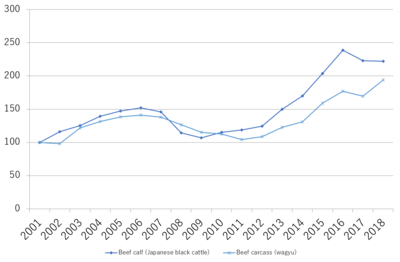

The beef tariff is 26.6% for fiscal 2019, more than ten percentage points lower than before the tariff reduction began under the TPP-11, which includes three major beef exporting countries: Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. The conventional wisdom is that a lower tariff means a lower domestic price, thus significantly affecting Japanese farmers. Yet a look at the following graph debunks it. The graph shows changes in the price indexes for wagyu (Japanese cattle) calves and carcasses (the vertical axis) over recent years (the horizontal axis), with both indexes in the base year of 2001 being 100. The price of domestically-produced wagyu beef, which has been on the rise, is at an all-time high now.

Japan's domestic beef industry is not affected at all; rather, it is thriving so astoundingly that it can be described as having reached a bubble. This also holds true for pork, which is totally unaffected by a lower tariff.

What about the income of the farmers eligible for compensatory measures associated with the TPP and a Japan-US FTA?

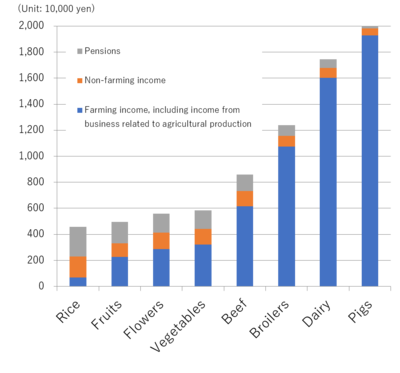

As the graph below shows, the average annual income is more than 8 million yen (US$ 73 thousand) for beef farmers, 17 million yen ($155 thousand) for dairy farmers, and 20 million yen ($182 thousand) for pig farmers. ("Non-farming income" primarily indicates employee salaries. The graph shows rice farming is mostly done by part-time farmers whose income comes primarily from employee salaries as well as elderly pensioners.)

The TPP or a Japan-US FTA might result in a slight reduction in farmers' income. In this case, should Japan's taxpayers, whose average annual income is around 4 million yen ($36 thousand), have to finance subsidies for these high income earners?

The Japanese public knows little about the country's agricultural industry or farming communities

Why does such a thing happen?

This is because most Japanese people distance themselves from the farming industry and communities and they have no idea what is going on there.When the public think of the farming industry and communities, they generally picture those before World War II. Indeed, farmers in prewar Japan, especially tenant farmers, were so poor that they were more like serfs or peasants. Tenant farmers had to pay a half of their crops to their landlords as rents. During the Showa Depression of the early 1930s, farmers in the Tohoku region had no choice but sell their daughters just to survive. That was just like the world of Oshin, a protagonist featured in the Japanese TV drama of the same name. Kunio Yanagida and other government agricultural officials in prewar Japan sought to salvage farmers from poverty.

What has changed?

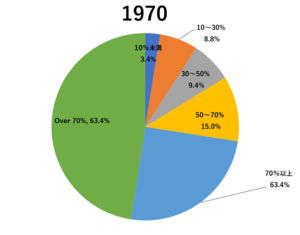

Farming communities have. The pie chart below shows the breakdown of the rural communities in Japan by percentage of farm households. According to the chart, rural communities where farm households accounted for more than 70% represented 63.4% of all such communities in 1970. In short, rural communities consisted largely of farmers.

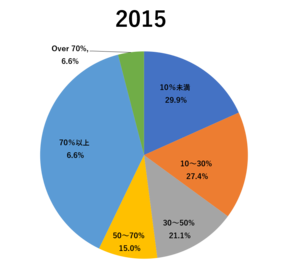

In 2015, however, rural communities where farm households accounted for more than 70% represented only 6.6%, while those where farm households accounted for less than 30% represented 57.3% (see the pie chart below). This is the result of an increase in the number of households headed by salaried workers who worked at factories or local government offices in farming communities.

"Farming communities" are no longer farming communities.

The agricultural industry has also changed.

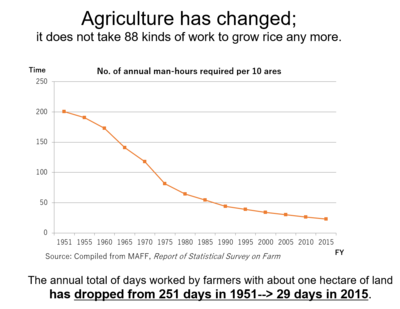

In the past, rice farming was said to take much time and effort. Legend has it that the Chinese character for rice can be read as eighty-eight because as many as 88 kinds of work are needed to grow rice. Nowadays, however, the progress of mechanization has significantly reduced the annual number of man-hours required to grow rice per ten ares, as the chart below shows. On the assumption that farmers work eight hours a day, the average number of days worked by farmers with about one hectare--the average farmer in all the prefectures in Japan except Hokkaido--has plummeted from 251 days in 1951 to 29 days in 2015. In short, they work for less than a month as rice farmers.

Half a century ago, old women who were hunchbacked as a result of the hard work of rice planting were often seen in farming communities. Now they are rarely seen because machines have taken over the work. There are no "Oshin" any more.

Also changed are farm households.

Above all, their income has increased. It has been higher than the income of salaried workers' households since 1965. Now, poverty is non-existent in farming communities.

The dairy bubble

Despite all that, the Japanese public still see farmers and farming communities as being poor and in need of support.

In TV news programs, commentators who stress the need to expand the production scale of rice farming for more efficiency are often met with questions from the anchors, who express concern about small part-time farmers. There is no need for income compensation since these part-time farmers do a small amount of farm work on weekends, as has been shown in the chart.

In a recent newspaper article I read, a reporter interviewed dairy farmers, who said that their business will be significantly affected by the TPP or a Japan-US FTA. However, the domestic dairy market will be liberalized only for whey and natural cheese for making processed cheese. Only a tiny proportion of domestically-produced raw milk goes to these products. Tariffs on butter and skimmed milk powder, two of the major dairy products, will not be reduced.

When asked by reporters, no farmers would dare to deny the prospect that they will be affected. This particular reporter interviewed farmers in the belief that they will be affected. This is because the public expect such an article.

A separate newspaper reporter well-versed in the farming industry in Hokkaido admitted to me that she cannot write an article suggesting a dairy bubble in the prefecture.

It is questionable that even the lawmakers of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who are backed by farmers fully understand the business conditions pig and other livestock farmers are in. Are they aware that the government aims to use taxpayers' money to provide income compensation for high income earners with an average annual income of 20 million yen ($182 thousand)?

Do they know the total number of livestock farmers in Japan? There are 46,000 beef farmers, 15,000 dairy farmers, and 4,000 pig farmers in this country. Dividing these numbers by 289--the total number of single-seat constituencies for the House of Representatives--produces the average numbers of these types of farmers per constituency: 160 for beef farmers, 51 for dairy farmers, and 14 pig farmers. They are inconsequential constituents.

Should the livestock industry be protected?

What are some of the reasons for protecting Japan's livestock industry?

Poverty may not be a reason but what about food security?

Except for a small number of dairy and beef cattle that are raised on pasture, the overwhelming portion of Japan's livestock is fed with corn, soybeans, and hay from the US and other countries. The Japanese livestock industry would be dealt a devastating blow if the sea lanes are interrupted and the import of feed is stopped as a result. The industry would be of no use in times of food crisis.

The livestock industry does not benefit the environment as it discharges much excreta as a by-product. The nitrogen content of the excreta has thus built up in large quantities across Japan. The same process has caused the blue baby phenomenon in Europe. The livestock industry also gives off methane--a greenhouse gas more powerful than carbon dioxide--through cattle belching. There are thus global moves to reduce the industry itself. They include the development of technologies to produce plant-based meat and cultured meat.

Food security may be relevant to rice and a few other crops. The fact remains, however, that 50 years of the acreage-reduction (gentan) program has reduced farmland resources vital to food security. The argument for agricultural protection from a multifunctionality perspective seems unconvincing. Such benefits as water resource recharging and flood control cannot be gained unless paddies are used for growing rice. Yet the government has been pushing for the gentan program that denies this original usage. All government arguments prove to be false.

Japan's agricultural interests have taken advantage of the public ignorance of the industry and farming communities to receive large amounts of government funds.

Private companies that see their business deteriorating usually try to rebuild their management. They would not blame the government for their own business deterioration. The agricultural interests may argue that the tariff reduction and elimination are the government's fault. But they have nevertheless enjoyed high levels of protection that are never seen in other industries. This has been made possible by having Japanese consumers--including people worse-off than average farmers--pay high prices for food products. Protective measures to date have been too lavish to be justified.

The agricultural interests may also justify such measures by saying that they have been financed by government funds. But government funds come from taxpayers--their fellow citizens. It is about time they stop depending on the central government. Seeing people always begging for government support or protection, few young people would feel like becoming their successors.

"Protection" of agriculture inhibits industrial independence

Before WWII, Tanzan Ishibashi (1884-1973), the 55th prime minister of Japan, condemned people surrounding farmers:

They argue that Japanese agriculture cannot possibly stand on its own as an industry and thus calls for protective tariffs. They argue that there is a need for low-interest loans [...] The government, the Diet, the Imperial Agricultural Association, scholars, newspaper reporters, and practitioners all find every opportunity to stress that agriculture is in a sorry state. They all base their argument on the premise that agriculture does not pay as an industry. All leading intellectuals and institutions try to convince farmers that farmers cannot stand on their own feet, thus weakening their resolve. They also try to convince farmers that farming is not worth the effort, thus dashing their glimmer of hope. These are the root cause of the miserable state of agriculture today.

Kunio Yanagida (1875-1962), the country's best scholar in public agricultural policy, called on farmers to have a spirit of self-help that does not depend on the state or the government.

>Petty philanthropists in society often emphasize that the populace must be helped. As I see it, this constitutes a profound contempt for them. I argue back, "why on earth should they not be encouraged to help themselves?" Self-help, progress, cooperation, and mutual help are the main aims of industrial associations (agricultural cooperatives).

Kunio Yanagida thought of desirable agricultural cooperatives as organizations in which farmers join hands (cooperation and mutual help) to take on any challenge on their own. He did not think of them as organizations eager to elicit protective measures or subsidies from the state through political movement.

The blame should also rest with lawmakers who count on the vote of farmers in exchange for protecting them as well as with people who seek the prolonged life of their organizations. Sen Tsuda (1837-1908), the father of the founder of Tsuda University, Umeko Tsuda, established Japan's first private agricultural school. Around this time, Sapporo Agricultural College, a public institution, was launched. An advocate of American Protestantism, Mr. Tsuda tried to train leaders of Japan's agricultural industry who would engage in farm management from the perspective of business administration based on the spirit of autonomy and independence without relying on the government. He severely criticized the government policy of protecting agriculture as follows: (Note: The Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce is the predecessor of MAFF and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry)

The success of private enterprises is generally contingent on the entrepreneurs relying on their own power and devoting all they have to their business. However, governmental protection will likely result in instilling a speculative spirit in people not eager for their business and thus encourage them to earn easy money, or in imbuing people who lack an independent spirit with a sense of dependence for starting up a business. Because these people are not sincerely engaged in their business, they cannot manage it to the end. Moreover, they can cause harm to sincere entrepreneurs and even weaken the country's public sector as a whole in the end.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce should revisit its history of protecting the industry. It will not be able to identify any outcome that has achieved the original aim. I must join other intellectuals in condemning the fact that the Ministry's protection strategy inhibited the private sector.