Media Global Economy 2019.06.28

The true reason for sluggish exports of farm produce lies in the vested interests of Japan's agricultural circles, which hinder export competitiveness

On June 4, the Japanese government compiled a new export expansion policy for agricultural, forestry and fishery products from Japan. The policy calls for concentrating the authority for international negotiations as well as export procedures and examinations solely on the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF); currently this authority is shared between MAFF and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The policy reportedly places special emphasis on a single-window mechanism for domestic examination to address import restrictions imposed by foreign countries under the cover of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures as well as on international negotiations aimed at removing or relaxing such restrictions.

Political analysts believe that the new policy is intended to secure farmers' votes in the rural constituencies where the governing Liberal Democratic Party fought a hard fight in the last House of Councillors election. The postponement of an agreement in the Japan-US trade negotiations until after the upcoming House of Councillors election may be backfiring. Japan's agricultural circles are voicing concerns that the government will make concessions to the Trump administration over farm tariffs. To allay such concerns, the Abe administration apparently wants to show that it is giving adequate attention to Japan's agriculture and farmers.

Regardless of the underlying motive, promoting the export of farm and other products is a relevant strategy to maintain the vitality of rural areas amid a declining population. And I don't intend to deny the importance of negotiations aimed at relaxing or removing non-tariff measures taken by other governments. Among such measures are SPS measures and other measures ostensibly designed to protect food safety. These measures are increasingly used as non-tariff measures in farm trade in a world where it is difficult for governments to take traditional trade-restrictive measures such as tariffs, with the GATT/WTO regime working satisfactorily, if not perfectly.

Why is Japan failing to increase farm exports?

Yet removing non-tariff measures alone will not boost farm exports from Japan.

Let us recall that Japan exports rice to Southeast Asian countries that impose no such non-tariff measures for this particular product. But Japan's rice exports to these countries remain sluggish. Why? I have asked officials at Japanese trading companies. They have come up with a simple answer: Japanese rice is high in quality but very low in affordability.

In other words, Japanese rice is not price competitive. Any export strategy formulated by MAFF disregards prices. MAFF ignores the price competitiveness of Japan's farm products, arguing that quality should sell well in international markets; however, it stresses the need for tariffs when it comes to the import of farm products, citing the low price competitiveness of domestic farm products.

Import tariffs would be unnecessary if Japanese consumers appreciated the high quality of domestic farm products and bought them for prices two to three times higher than those of imports. Import and export are two sides of the same coin in international trade. If the domestic price of an item is higher than the international price of it, that particular item will be imported, and vice versa. The price gap is the primary driver of both import and export.

At a glance, MAFF's action seems schizophrenic. Yet Japan's agricultural circles including MAFF do not expect that farm exports, which remain insignificant, will increase to the level that can save the country's agricultural industry, although an increase in exports would be most welcome for them.

An increase in imports is the last thing Japan's agricultural circles want. They believe that more imports from the US and Australia could put Japan's agricultural industry on the verge of extinction. Accordingly, they argue that domestic farm products are not price competitive in relation to imports. This argument is tantamount to maintaining that prices matter.

Vested interests of Japan's agricultural circles hinder export competitiveness

MAFF is more than aware that domestic farm products are expensive. This is why it stresses that tariffs on imports are necessary. If MAFF wants to promote exports in earnest, it has to bring domestic prices down significantly. That, however, would undermine the core of the vested interests that Japan's agricultural circles enjoy--the high rice price policy.

By maintaining high rice prices, MAFF has succeeded in keeping small-scale, part-time farmers and elderly farmers afloat. These farmers have deposited their income from non-farming work (salaries for working at factories, schools, hospitals, etc.)--which is as much as four times larger than their farming income--as well as their annuities into their accounts at the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA). With total deposits of more than 100 trillion yen, the JA Bank is second-biggest mega-bank in Japan.

High rice prices constitute the basis for the development of JA. Reducing domestic prices of farm products, especially rice, would undermine the very existence of JA, which is at the core of Japan's agricultural circles.

This is why the Agricultural Village [agricultural circles sharing the same vested interests]--MAFF at the top and all the way down to researchers at agriculture departments of universities--cannot possibly argue for reducing prices and increasing competitiveness to boost exports.

The gentan program has been reining in rice productivity

Does this state of affairs really benefit the maintenance and development of Japan's agriculture?

The abolition of the staple food control system in 1995 has meant that the government no longer buys up rice from farmers at high prices. Since then, rice prices have been kept high under the program of gentan [reduction of the acreage under cultivation]. The gentan program is designed to maintain high rice prices by reducing the supply (production) of rice. The only way to do so amid declining demand is to reduce production. As I pointed out in my earlier article "Japanese agricultural policies destroying the world's most sustainable paddy field farming", Japan's agricultural administration and industry have done all they can to reduce rice production.

For the purpose of reducing rice production, it is not desirable to boost productivity, or more specifically, the yield per unit area. Improving rice varieties is instrumental in boosting the yield per unit area. Since the gentan program was launched, however, researchers at national and prefectural agricultural experiment stations have been strictly prohibited from engaging in variety improvement aimed at increasing the yield per unit area. Not a few of them still express how sad and angry they felt at this prohibition.

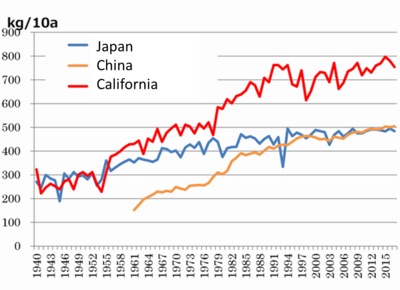

Now the unit yield of rice produced in Japan is 40% lower than that of rice produced in California. To my chagrin, China has surpassed Japan in this regard as well. The unit yield of Chinese rice was half that of Japanese rice half a century ago.

A rice variety that is superior to Californian rice in unit yield has already been developed by a Japanese company and is used by a few full-time farmers in Japan. But agricultural cooperatives, which supply rice seedlings to many part-time farmers, would not dare to adopt this particular variety for fear that a resultant increase in production will drag down rice prices. The abolition of the gentan program and the introduction of a variety on par with California rice in terms of unit yield will reduce the cost of rice production by 30%.

Boosting export by abolishing the gentan program

All Japan's agricultural circles see is the domestic market.

Nevertheless, if they abolish the gentan program and reduce rice prices for better price competitiveness of Japanese rice, they can develop global markets for exporting the product. The benefit is two-fold; rice exports obviate the need to reduce rice production and help to sustain rice prices.

Now, let me expand on what I have explained in my earlier article "Japan's export of rice violates the WTO rules" (https://www.canon-igs.org/en/article/20190306_5630.html).

In fiscal 2014, the price of domestically-produced rice fell below that of Californian rice. Within a tariff-free import quota of 100,000 tons of rice as a staple food, only 12,000 tons were imported. Japanese trading companies exported Japanese rice to California. Some Japanese rice producers began to maintain that their product can be competitive even if the rice tariff is abolished.

The very price of domestic rice is maintained under the gentan program aimed at reducing supply. Unfortunately, the Abe administration's subsequent policy to strengthen the gentan program resulted in a higher domestic rice price and a wider gap between domestic and international prices. If the gentan program is abolished, the price of domestic rice will be even lower and the yield per unit area, which has been kept low, will rise. Full-time farmers are one thing; semi-business farmers and part-time farmers are quite another. The former and the latter should not be treated on the same footing. If the recipients of direct subsidies are limited to full-time farmers, they will be better able to pay their land rent. As a result, farmland will be concentrated in their hands. Their total farmland will be larger, and small tracts of farmland distributed here and there will be consolidated. This in turn will pave the way for more efficient agricultural production. The abolition of the gentan program and direct subsidies to full-time farmers will boost the productivity and price competitiveness of Japanese rice, whose quality is highly evaluated in the world. This will allow Japan to cultivate overseas markets for this product.

Given that California rice was 11,464 yen (Japan's import price) in 2018, Japan's rice could be exported at a price of about 13,000 yen because of its higher quality. If production adjustment (gentan program) is discontinued, the price of rice will fall to about 7,000 yen. If a trading company purchases it at 7,000 yen and sells it at 13,000 yen, it will make a profit without fail. As a result, the supply of rice will decline in the domestic market and the domestic rice price will soon rise to 13,000 yen. Economists refer to this as price arbitrage.

In short, exports serve to prop up the domestic rice price, which seems to fall significantly only if the domestic market is considered. In fact, the domestic rice price did not fall below the international price in the early part of the Meiji Era [1868-1912], when rice was a major export item for Japan.

Since the price of rice will rise just after the abolition of the gentan program, rice production will increase significantly the following year. Moreover, if the abolition results in the planting of rice varieties with higher yields per area, which has been restrained so far, rice production will be more than 15 million tons and 7.5 million tons of rice will be exported. Because the total value of exported rice amounts to 1.5 trillion yen, only the export of rice will suffice for achievement of the central government's export target, 1 trillion yen, for all of farm and fishery products and food inclusive.

If, as in the U.S. and EU, full-time farmers who will be affected by price decline receive compensation for the gap between the existing price of 14,000 yen and the declined price of 13,000 yen (the covered quantity is 3 million tons, 40% of the current production), this will require 50 billion yen, which is far less than the 400 billion yen paid by taxpayers for the acreage reduction program. Moreover, if small-scale farmers withdraw from the rice industry due to rice price decline, the farm size of full-time farmers will expand, resulting in lower costs and increasing profits. Therefore, the compensation will be only temporary and could be abolished someday.

Kamezo Nishihara's quest for rural development

In prewar Japan, a groundbreaking farming and rural reform was practiced in Kumohara-mura in Yosa-gun (now Fukuchiyama City), which was said to be the poorest village in Kyoto at the time. The reform was led by Kamezo Nishihara (1873-1959), a power broker of the prewar political world famous for his efforts to promote what is known as Nishihara Loans, a series of loans provided to China. Although he assumed the mayoralty of Kumohara-mura in 1935, Nishihara began to dedicate his full-fledged efforts to the administration of the village in 1938, after his scheme to have former Army Minister Kazushige Ugaki run for prime minister was scuttled by the Ministry of Army.

Nishihara, who was aiming to rescue and develop the economy of troubled East Asia, maintained that Japan should promote rural development in a wider context of the international economy. He put forward the idea of reducing product prices to lessen consumer burden and make Japanese industries more competitive in international markets. He also put this idea into practice.

Nishihara said: "If we live in a global economic environment and hope to stabilize our living situation and increase our happiness, we must introduce the principle of "High Quality, Low Price" and establish social organization where cheap products of high quality are inevitably provided."

Providing "quality goods at low prices"-- this is just what Japan's present-day export industries, including Toyota, Canon, and UNIQLO, are aiming to do.

Unfortunately, however, Japan's agricultural circles remain unaware of the importance of price competitiveness when it comes to exports. Amid a declining population and dwindling demand for local products, a global perspective is essential to the revival and revitalization of Japan's agriculture and regional economies. The principle of "High Quality, Low Price" advocated by Nishihara is also essential to compete in international markets.

Nishihara's initiative transformed the once-poor Kumohara-mura into a bustling village. Prior to the Second World War, political leaders such as Fumimaro Konoe and Kuniaki Koiso visited the village and praised the achievement, while after the war, it was honored by GHQ as a model Japanese farming village.

For genuine food security

The strategy for Japan should be to export rice and import wheat and beef during peacetime. If a food crisis results in the discontinuation of imports, the Japanese people can keep hunger away with rice that would otherwise have been exported. At the same time, the farmland resources retained for exporting rice can be put to best use to cultivate potatoes and other high-calorie crops. In this way, the quantity of food necessary for the lives of Japanese citizens can be secured.

Rice exports during peacetime help to secure rice stocks and agricultural resources in case of crisis. Such stocks will not entail any financial burden: no warehouse fees or interest will be incurred. The financial burden associated with domestic stocks will be dissipated.

This is the normal strategy for food security practiced by almost all nations. In short, free trade during peacetime ensures food security in cases of crisis.

Promoting exports in earnest will require not superficial but fundamental administrative reform in agriculture. I doubt, however, that the Abe administration, which covered its strengthening of the gentan program with fake news that the program had been abolished, has the courage to carry out such reform.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Dr. Yamashita's column in "RONZA" on June 10, 2019.)