Media Global Economy 2019.06.04

Did Tokyo lose to Seoul in the WTO's ruling on the import ban on marine products from the areas affected by the nuclear accident?: The course of action that Japan should take.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) has recently ruled in favor of the South Korean government's ban on imports of marine products from the areas affected by the accident at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant. The WTO's Appellate Body reversed the earlier decision of a dispute settlement panel ("Panel") that supported Japan, which had brought the case to the WTO. The ruling by the higher authority in the WTO's two-stage dispute-settlement system means that the South Korea's import ban will remain in place.

Commenting on the ruling, Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga contended that the argument that Japan has lost the case is off the mark. The top government spokesperson argued that the Appellate Body upheld the Panel's recognition that food products from Japan are scientifically safe and substantially meet South Korea's safety standards.

This argument was refuted by some scholars of international economic law, causing a stir. These scholars noted that the Panel's report does not contain a passage to the effect that Japan's food products are safe (the front page of the Asahi Shimbun on April 23).

From what I have learned by reading media reports and experts' commentaries on this case, I agree with the Japanese government's claim that Japan has not lost the case. However, the evidence put forward for this argument did not reflect an accurate understanding of the Appellate Body's report. The scholars' criticism on this point is justified.

The following paragraphs explain why. The problem, however, is that although the ruling does not necessarily represent a defeat for Japan, it allows South Korea to continue with an import ban that likely contravenes WTO rules.

Food safety and the WTO SPS Agreement

Let me briefly explain why the WTO has come to impose regulations with regard to food safety and trade.

The introduction of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures designed to prevent the entry of diseases and pests through the import of foods, animals and plants are regarded as a legitimate instrument for governments to protect the lives, physical safety, and health of their population.

SPS measures, however, are increasingly being used to protect domestic agriculture amid growing difficulty in resorting to traditional means of protecting domestic industries that are under increasing pressure to lower tariffs through international negotiations. SPS measures used as disguised protectionism should be restricted or removed altogether in light of the need for trade liberalization in a world where we import many different food products from all around the globe for consumption.

Nevertheless, even SPS measures that are genuinely designed to protect the lives and health of the people have some kind of impact on trade. If anything, such SPS measures are not so easily distinguishable from those designed to restrict trade.

This vague distinction means that it is necessary to harmonize the benefit of food safety with the benefit of food trade and consumption.

In fact, efforts to strike a balance between these two different requirements were made as part of the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations, which were initiated in 1986. These efforts culminated in the WTO SPS Agreement in 1994. The SPA Agreement sought a scientific solution and thus decided to disapprove SPS measures that are not based on scientific evidence.

An SPS measure that fails to provide scientific evidence showing that there is a risk to life or health, or otherwise fails to reduce that risk, is regarded as being designed to protect domestic industry under the SPS Agreement.

On that basis, the SPS Agreement seeks to harmonize the SPS measures of Members with international standards because unified regulations will contribute to trade facilitation.

Mechanism of the WTO SPS Agreement

Let me briefly explain how the SPS Agreement works.

First of all, each Member may establish its own appropriate level of protection (ALOP). ALOP can also be defined as an acceptable level of risk, which might be one death per 10,000 people or 100 million people. The establishment of ALOP is the sovereign right of each Member, which may define its ALOP as zero risk if that is consistent with the provisions of the SPS Agreement explained later.

Yet each Member must "avoid arbitrary or unjustifiable distinctions in the levels it considers to be appropriate in different situations, if such distinctions result in discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade" (Article 5.5). This is based on the principle of consistency. Under this principle, Members may not, with regard to a similar risk, reduce the level of protection to allow for a lenient measure on some occasions and raise the level of protection to demand more strict measures on others.

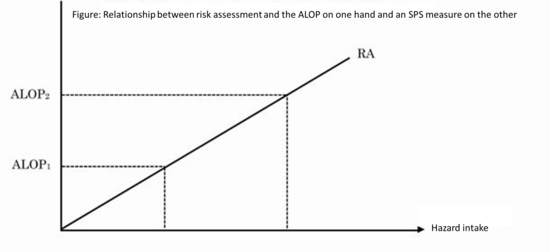

After establishing its ALOP, each Member decides on its SPS measures based on scientific appraisal ("risk assessment"). The figure below illustrates this relationship. The vertical axis shows the level of risk (one death per X people) while the horizontal axis denotes the SPS measure (the level of hazard intake). The relationship between the two is shown by the positively sloped straight line. The closer a point along this line is to the origin, the smaller the acceptable level of risk is and thus the higher the level of health protection. The acceptable level of hazard intake is therefore lower. If an ALOP is the objective, an SPS measure is an instrument to achieve it. While an SPS measure is required to show scientific evidence, an ALOP is not. Once an ALOP is established from a political or policy perspective, that ALOP and risk assessment determine the SPS measures.

The SPS Agreement requires SPS measures:(i) To be based on scientific principles (Article 2.2; meaning that risk assessment must be conducted as stipulated in Article 5.1); (ii) Not to arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between Members where identical or similar conditions prevail, including between their own territory and that of other Members (Article 2.3; meaning that no different treatment is allowed under identical or similar conditions); (iii) Not to be applied in a manner which would constitute a disguised restriction on international trade (Article 2.3); and (iv) Not to be more trade-restrictive than required to achieve the ALOP (Article 5.6).

The WTO Appellate Body's decision

The Appellate Body nullified the Panel's two decisions: (i) that South Korea's measure is more trade-restrictive than required (Article 5.6), and (ii) that South Korea's measure is discriminatory against Japanese marine products (Article 2.3). (The following discussion builds in part on Kawase, Tsuyoshi's, "Kankoku Hoshasei Kakushu Yunyu Seigen Jiken Saiho" [the case of South Korea's import bans for radionuclides revisited], RIETI, 2019).

Kawase summarizes the Appellate Body's decision on whether South Korea's measure violates Article 5.6 as follows:

The Panel found that South Korea's ALOP in this case consists of three major elements (i) maintenance of radioactivity levels in food at levels that exist in the ordinary environment; thus, (ii) within the upper radiation dose limit of 1 mSv/year, (iii) maintenance of levels of radioactive contamination in food as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA). The Panel, however, focused solely on element (ii). It failed to address such issues as whether these three elements are independent from one another, how they interact with one another, and whether element (ii) connotes the qualitative elements of (i) and (iii).

The Panel had the duty to examine whether the alternative measure proposed by Japan (restricting only food products whose cesium content is no less than 100 Bq/kg, a level that keeps the per capita radiation exposure below 1 mSv/year) would achieve South Korea's multi-faceted ALOP. However, the Panel failed to examine all the three elements of South Korea's ALOP; it only found that the alternative measure would achieve an exposure level significantly below 1 mSv/year.

Such a vague ALOP is problematic. This is because "although precedents of the Appellate Body suggest that ALOP should not necessarily be quantitative in nature, the ALOP should be 'precise' enough not to impede the fulfillment of the duties under the SPS Agreement, and Members that take SPS measures have the prerogative and duty to establish such measures accordingly" (Kawase). In practical terms as well, it is quite questionable how such a vague ALOP can serve as a basis for conducting risk assessment and establishing SPS measures.

In short, "what it all boils down to is that the Appellate Body likely thought that the Panel should have come up with a clear conclusion that ALARA and the 'under the ordinary environment' requirement have no meaning per se and indicate the standard of 1 mSv/year" (Kawase). The Appellate Body thus seems to have criticized the Panel for failing to explicitly state that South Korea's ALOP is inappropriate. This points to the illogicality of the Panel, not to a defeat for Japan.

On whether South Korea's measure violates Article 2.3, the Appellate Body refuted the judgement that the Panel had made based solely on radioactive contamination levels in food products per se in relation to the criterion of whether a measure "discriminates between Members where identical or similar conditions prevail, including between their own territory and that of other Members." The Appellate Body stated that in making such a judgement, consideration should also be made to the environment in the producing country, i.e., Japan, which suffered the nuclear accident. "With regard to contamination levels in food products per se, the Appellate Body also stated that the Panel had focused only on whether the actual contamination levels in food products are below South Korea's safety standard (100 Bq/kg for cesium), of which the Panel approves, and failed to examine the potential for food contamination stemming from different levels of radioactive contamination between Japan and other areas" (Kawase).

This decision by the Appellate Body is questionable. It is a food product that might affect health. The question is to what extent a food product poses health hazards regardless of where it is produced. How can risk assessment be made with regard to potential contamination that no one knows exists.

It should be noted, however, that what the Appellate Body found problematic here is the misjudgment on the part of the Panel. The Appellate Body did not make a judgment on what may result from the examination of potential contamination. Japan's argument on this issue was not accepted. But Japan could have won the case if the Appellate Body had found that South Korea's measure violated the SPS Agreement on another issue.

At any rate, the Appellate Body stated that only the Panel had erred in its judgement; it did not state that South Korea's measure does not violate the SPS Agreement. If the Panel had clearly pointed out the violation of Article 5.6, the Appellate Body would likely have upheld the Panel's conclusion that South Korea's measure violates the SPS Agreement.

A few questions about how the Japanese government acted

The question remains, however, as to whether the Japanese government made a sound case or took the right approach in light of three considerations.

The first consideration is that in past dispute cases concerning the SPS Agreement, the Appellate Body has often acknowledged violations of Articles 2.2 and Article 5.1, both of which concern risk assessment (see Yamashita, Kazuhito, Shoku no Anzen to Boeki (World Trade Organization Agreement on the Agreement on the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures) [in Japanese]. Nippon Hyoronsha, 2008, p. 56).

In eight such cases up to 2008, the Appellate Body upheld all five allegations of violations of Article 2.2 and all eight allegations of violations of Article 5.1. By contrast, the Appellate Body did not uphold the only one allegation of violation of Article 2.3, the violation of which the Japanese government complained in this case; it upheld just one of the three allegations of violations of Article 5.6.

Shouldn't Japan have placed the question--how South Korea could have conducted risk assessment based on the vague ALOP to come up with the blanket import ban--at the forefront of the legal battle? For the benefit of litigation efficiency as well, Japan should have complained about the violation of Articles 2.2 and 5.1 to win the case.

The second consideration is that it is difficult to fully substantiate a violation of Article 5.6.

Article 5.6 calls on Members to ensure that measures to achieve the ALOP are not more trade-restrictive than required, taking into account technical and economic feasibility. Such measures are considered more trade-restrictive than required if there is a less trade restrictive alternative measure available. What is a less trade restrictive alternative measure like? Take, for example, the case in which a country wants to restrict health-hazardous agrochemical residues in imported corn. This country may opt for a blanket import ban, but a less trade restrictive alternative measure for the country may be to call on exporting countries to impose restrictions limiting agrochemical residues to a certain level and conduct surprise checks at ports of entry to see if these exporting countries are complying with the restrictions.

The question of whether a measure violates Article 5.6 or not is examined in light of three criteria: (i) whether "there is another measure, reasonably available taking into account technical and economic feasibility"; (ii) whether there is another measure that achieves the appropriate level of protection (ALOP); and (iii) whether there is another measure that is significantly less restrictive on trade (meaning that the alternative measure is acceptable if it is somewhat--instead of "significantly"--restrictive to trade). These three criteria are multi-layered. In order to make a case that a measure taken by a Member violates Article 5.6, a complainant must establish the availability of an alternative measure that meets all the three criteria. With regard to criterion (iii), the note to Article 5.6 states that a measure is not more trade-restrictive than required unless there is another measure that is significantly less restrictive to trade. This idea is that a measure that is somewhat trade-restrictive than another measure is acceptable unless it is significantly trade-restrictive (see Yamashita, op. cit., p. 101).

In short, it is difficult to establish a violation of Article 5.6 even if the measure in question is somewhat restrictive to trade.

The third consideration is that Japan should likely have made the case that South Korea's measure violates Article 5.5, which concerns ALOP, instead of Article 5.6, which concerns measures.

Establishing a violation of Article 5.5 requires meeting three criteria: (i) different levels of protection have been applied in "comparable" different situations; (ii) distinctions in the levels of protection are "arbitrary or unjustifiable"; and (iii) distinctions in the levels of protection "result in discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade."

The Appellate Body took note of the provision in Article 2.3 that SPS measures should not "discriminate between Members where identical or similar conditions prevail, including between their own territory and that of other Members" in refraining from acknowledging a violation of that article. The Appellate Body maintained that such conditions include ecological and environmental conditions in Members--the nuclear accident in Japan in this context. Yet Article 5.5 does not have such a language or a provision. In the case of EC Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products (Hormones), the dispute settlement panel stated that "situations involving the same substance or the same adverse health effect may be compared to one another." The Appellate Body concluded that different situations cannot be compared "unless they present some common element or elements sufficient to render them comparable" and that if the situations "are totally different from one another, they would not be rationally comparable and the differences in" the ALOP "cannot be examined for arbitrariness." In the Tokyo-Seoul dispute, the common element (hazard) of cesium renders the different situations comparable.

The alternative measure proposed by Japan (restricting only food products whose cesium content is no less than 100 Bq/kg, a level that keeps the per capita radiation exposure below 1 mSv/year) is identical to South Korea's safety standard of 100 Bq/kg in terms of cesium content. The ALOP of less than 1 mSv per person per year is an international standard as well. South Korea's measure of a blanket import ban corresponds to zero risk rather than to the ALOP of less than 1 mSv. Therefore, Japan could have argued that South Korea's ALOP is "arbitrary or unjustifiable" in relation to Japan.

The WTO and other countries are not problem-free

The Appellate Body's latest ruling highlighted a major problem with WTO dispute settlement procedures as well.

Although the Appellate Body stopped short of finding South Korea's measure consistent with the WTO Agreement, the questionable measure will remain in place. This is because the WTO's Appellate Body can nullify the Panel's decisions but cannot make its own judgement on cases or remand them to the Panel for re-judgement.

The good news for Japan is that the Appellate Body's ruling is not applied to other economies taking similar import ban measures, such as China and Taiwan. The latest ruling does not justify the measures taken by these countries/territories. Japan is left with the option of learning from the ruling and bringing a case before the WTO against China, etc. to demand corrective measures.

A WTO ruling in a Chinese or Taiwanese case that blanket import bans violate WTO rules would allow Japan to increase its call on South Korea to take corrective measures.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Dr. Yamashita's column in "RONZA" on May 7, 2019.)