Media Global Economy 2017.01.12

Rather than being abolished, the Gentan System was strengthened.-We need to abolish the gentan policy even if we are not pushed by the United States to do so.-

The December 13 edition of the Nihon Keizai Shimbun published an editorial headlined "Do Not Reduce the Abolition of the Gentan Policy to an Empty Slogan." The editorial's claim was that it is ludicrous that the government is attempting to implement a policy aimed at revamping the gentan (rice acreage reduction) policy despite its plan to abolish it starting in fiscal 2018. I have called for the abolition of the gentan policy for many years and have no objection to that idea. The issue I want to address here is the editorial's premise that the Japanese government will abolish the gentan policy.

The abolition of the Gentan System was a false report

In 2013, the government reviewed its gentan (production adjustment) program. This decision was based on an agreement that was reached by lawmakers affiliated with farm organizations (norinzoku) for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had regained power, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. However, this news made the front page of a particular newspaper and the headline read "Gentan Policy to be Abolished" without inquiring of the norinzoku or the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Several other major newspapers followed suit.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his official residence barely touched on this policy decision, which was reached between the norinzoku for the LDP and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Yet Abe later declared that he had abolished the gentan policy. He said proudly that this was a feat that no one was able to achieve over the past 40 years. He made this claim not only in his administrative policy speech to the Diet, but also at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Immediately after it was reported that the gentan policy would be abolished, I questioned the chief of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries at length. "This review does not mean the gentan policy will be abolished. Why are you making such false claims?" He appeared annoyed and countered by saying "We never said we would abolish the gentan policy."

The Japan Agricultural News (Japan Agri News), a bulletin for Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, reported the news most accurately and with the most composure.

The Japan Agri News shined a spotlight on the responses to questions in the Diet given by Yoshimasa Hayashi, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (at the time), who believed that the gentan (production adjustment) was necessary. When I spoke at the Japan National Press Club around that time, the emcee introduced me in a curious way. Here is what he said: "Interestingly, the review of the gentan policy is the only issue that the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, and Mr. Yamashita agree on."

During a meeting of the Lower House Budget Committee held in February 2014, Prime Minister Abe was asked about the inconsistencies concerning the statements made by the LDP's top officials in charge of agriculture and forestry as well as the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries who stressed the need for the gentan policy, and his own remarks. Prime Minister Abe's response was that he merely made his remark so that it would be clear to the general public, and he retracted his remark that the gentan policy had been abolished. I thought that this remark would surely make headlines because Prime Minister Abe had admitted that he had made a false statement to the public in a Diet session. However, that did not happen.

In this manner, the abolition of the gentan policy, which is not going to happen, was etched in stone. When I recently made a television appearance and pleaded that the gentan policy needs to be abolished, the newscaster said to me "But hasn't it already been decided that the gentan policy will be abolished."

The most important policy for the agricultural policy triangle

In 2013, in the midst of news reports that the gentan policy would be abolished, prominent economists and former government bureaucrats asked me the following: "Is the report really true? The gentan policy is designed to ensure the high price of rice and is central to our post-war agricultural policies, and I don't believe that it can be abolished that easily. I can't believe that our agricultural policy makers, who do not even approve the acquisition of farmland by business corporations, would willingly make such a proposal."

This is what I told them:

"You're absolutely right. The media reports are completely false. The abolishment of the food control system was a result of the GATT Uruguay Round. Making drastic changes to agricultural policies such as the abolition of the gentan policy or policies for ensuring the high price of rice would require substantial environmental changes. Such changes are not taking place right now. It is stipulated in the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP) that rice tariffs will not be removed. Therefore, there is no need to reduce the price of rice by abolishing the gentan policy. Far from abolishing the gentan policy, the government will strengthen it. Those reports are false. They were reported by those who do not understand the essence of the gentan policy." They nodded to my response.

The gentan policy is a policy aimed at keeping rice prices high by reducing the supply of rice through the provision of subsidies to farm households. It is the most important policy for the agricultural policy triangle, which consists of the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, norinzoku, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Abolishing the gentan policy would involve much more drastic reforms than reforming the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives

Due to the high price of rice, small-scale part-time farmers with high cost continued to grow rice. This not only retained nogyohyo (votes from agricultural stakeholders), it made the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives into the second largest bank in Japan, as part-time farmers saved their earnings in agricultural bank accounts.

The abolition of the gentan policy would lower the price of rice by increasing supply. It would involve much more drastic reforms than reforming the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives. If the LDP or government had proposed the abolition of the gentan policy, the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives and farming communities would have been outraged and protest flags would be all over Nagata-cho and Kasumigaseki in Tokyo. However, the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, as well as farming communities, have been very quiet. Why is that? It is because they know all too well that the LDP and government reviewing the gentan policy did not mean that the program would be abolished.

What was the review of the gentan policy?

What then transpired when the gentan policy was reviewed in 2013?

The gentan policy is the government's decades-long policy of curtailing rice production. The government assigns production targets to farmers through prefectural and municipal governments, and only those who met the production targets are granted gentan subsidies.

If a farmer grows rice in a 10-hectare rice paddy, and if the production target under the gentan policy was set at 4 hectares, that farmer would not be granted a subsidy unless they are able to meet the production target for rice acreage reduction for all 4 hectares. On top of that, if all farms in the community does not meet the aggregate production targets in total, the community would be penalized by not being granted other forms of subsidies (such as those for machinery).

The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which regained power in 2009, changed the system so that farmers would be granted subsidies even if they are unable to meet their production targets. For the above example, farmers would be granted subsidies even if they are only able to reduce the rice acreage in just 3 hectares rather than 4 hectares, according to the amount of rice acreage reduction.

In exchange, farmers who meet all of the production targets for rice acreage reduction would be granted farmers' direct income compensation payments according to the rice acreage. The government used the direct income compensation payments as a bribe to get the farmers to meet the production targets for rice acreage reduction. In other words, they changed the system into one that involved two bribes: a subsidy for rice acreage reduction and the direct income compensation payments for the rice acreage by linking together the feats of meeting production targets with the direct income compensation payments system.

The LDP criticized the DPJ's direct income compensation payments system calling it a scattering of subsidies and pledged that it would abolish it. The DPJ granted direct income compensation payments even to small-scale part-time farmers who had very little agricultural income. It is no wonder that the LDP criticized this policy by calling it a scattering of subsidies. The review of the gentan policy in 2013 was carried out by the LDP, which had regained power, to re-examine the system in an effort to abolish the DPJ's direct income compensation payments system.

In 2014 subsidies for the direct income compensation payments system was cut by half. The direct income compensation payments system will be abolished completely by 2018, and the production targets for rice acreage reduction - its only link being the direct income compensation payments system - will also be abolished. To compensate for that, the government has drastically increased the amounts of the gentan subsidies by utilizing the money saved by cutting back on and abolishing the direct income compensation payments. This subsidy would be provided if rice as staple food would be replaced with rice as animal feed.

It is only the production targets for rice acreage reduction that will be abolished. Far from being abolished, the gentan policy will be strengthened. In fact, in 2007, during Abe's first tenure as prime minister, he abolished the production targets, just as they were in this review, and immediately repealed them after the price of rice dropped. Prime Minister Abe himself had implemented the policy five years ago and repealed it. This is not a feat that no one has been able to achieve over the past 40 years.

(Created by writer)

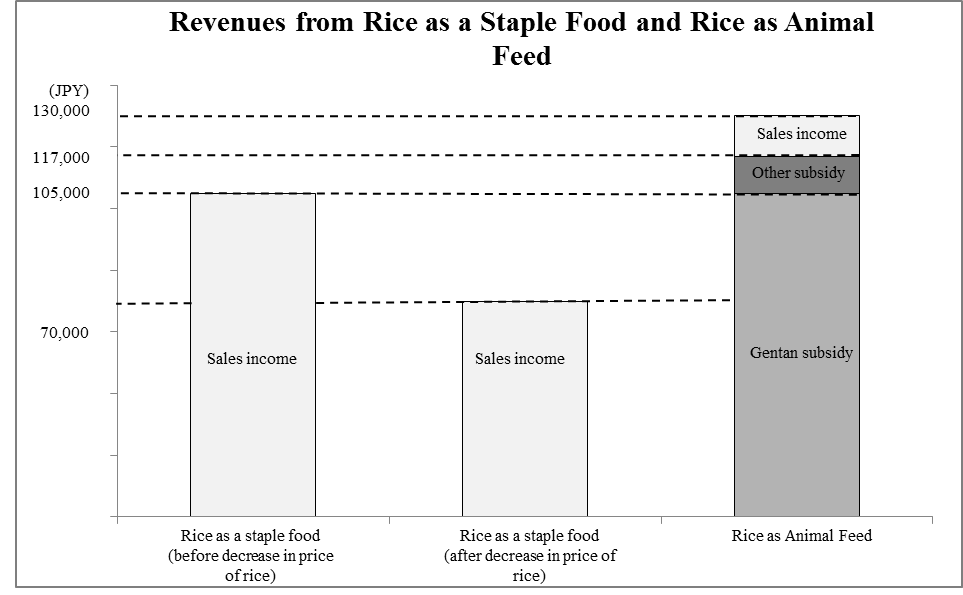

The review of the gentan policy had a profound impact. In 2014 the price of rice as a staple food fell to 70,000 JPY per 10 acres. Therefore, growing rice as animal feed was much more profitable, as it resulted in a revenue of 130,000 JPY, including 105,000 yen in gentan subsidies.

The government will continue this subsidy system. Under the Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, which was approved in a Cabinet meeting, the production target for rice as animal feed for the year 2025 will be 1.1 million tons. Promoting efforts to grow rice as animal feed is clearly highlighted in the Agricultural Competitiveness Enhancement Program, which was adopted along with the recent agricultural reforms?

Trump's America will file a complaint with the WTO

The production of rice as animal feed has grown steadily due to the increase in gentan subsidies. In 2013, which was before the review of the gentan policy, the crop acreage and production for rice as animal feed were 22,000 hectares and 110,000 tons, respectively. These figures have quadrupled to 91,000 hectares and 480,000 tons in 2016.

This, of course, entails an enormous financial burden. Nearly 100 billion yen will be collected through taxes in 2016 alone. If the goals stipulated in the basic plan are reached, 200 billion yen in taxes will be spent on animal feed. While the Ministry of Finance Japan asserts that this needs to be reassessed, the ministry currently does not have the power to stand up to the LDP.

A growth in production of rice as animal feed would result in significant decrease in the amount of corn for animal feed imported from the United States. If the United States were to file a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) concerning Japan's gentan subsidies, the United States would certainly win. If Japan does note abolish its gentan subsidy system, the United States will likely place a punitive tariff on cars imported from Japan. The auto industry, which is 7 times the size of the rice industry, will take a huge hit. If that were to happen, the only option would be to abolish the gentan policy.

Policies, ordinarily, are designed to provide the public with goods or services at an affordable price in exchange for a financial burden, much like medical policies. There is no other policy that raises the price of rice by collecting 400 billion yen in taxes and requiring the consumer to make an additional payment of 600 billion yen, which is what the gentan system entails. This means that every citizen, ranging from babies to the elderly, is required to pay 10,000 yen annually.

We need to abolish the gentan policy even if we are not pushed by the United States to do so.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Dr. Yamashita's column in "Webronza" on December 19, 2016.)