Media Energy and the Environment 2025.05.29

Leverage Trump’s Tariffs: Japan Should Phase Out Chinese Solar and Pivot to U.S. Energy Imports

Real Clear Energy(2025年4月29日)に掲載

The Trump administration is pressing Japan to cut its trade surplus, prompting Tokyo to consider concessions in automobiles, agriculture, and other sectors. Yet there is a far easier way to achieve the same goal—one that also advances Japan’s own national interests: rethink her energy policy that has single-mindedly prioritized decarbonization. By recalibrating that policy, Japan can reduce its surplus painlessly, as the key numbers that follow will demonstrate.

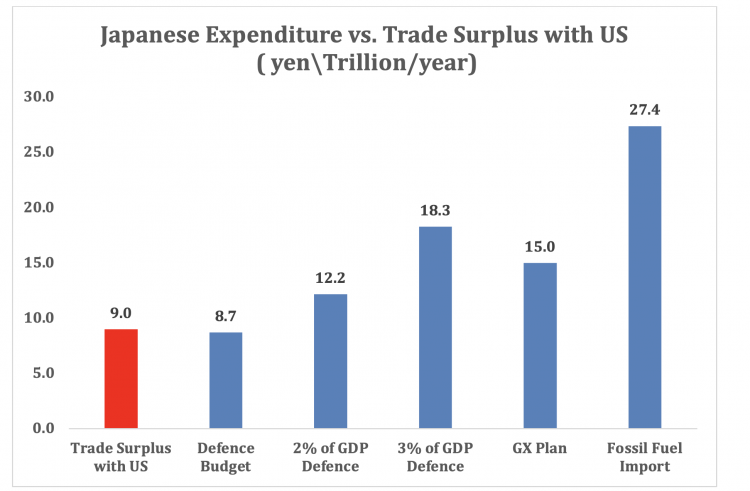

Japan’s annual trade surplus with the U.S. is about ¥9 trillion. How can Tokyo bring that figure down?

Defense spending is an oft-discussed lever. Japan now spends ¥8.7 trillion a year on defense. Raising the budget to 2% of GDP, as the government plans, would lift it to ¥12.2 trillion; pushing it to 3%, as U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby has urged, would raise the total to ¥18.3 trillion. A significant share of any increase would go toward U.S. equipment—money that arguably serves Japan’s own interests.

Yet the larger opportunity lies in energy.

Tokyo’s Green Transformation (GX) Implementation Plan—its flagship decarbonization strategy—aims to catalyze ¥150 trillion in new investment over the next decade, or roughly ¥15 trillion a year.

The centerpiece of the GX plan is an aggressive push for renewables and electric vehicles. Yet China now commands more than 90% of the global solar‑panel market and 60–80% of the key equipment for offshore wind; it also dominates the EV supply chain.

In practice, then, the GX plan would channel vast sums of money to China.

A principal goal of the Trump tariffs is to curb China’s unfair trade and investment practices. Abandoning the GX plan would therefore align squarely with U.S. aims, whereas continuing it would be hard for Washington to tolerate.

Japanese officials insist the GX strategy will spur economic growth, but in reality it would drive up energy costs and harm the economy. The Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth (RITE), an affiliate of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, estimates that the plan would shave ¥30 trillion off GDP every year by 2030.

Scrapping the GX plan is thus in Japan’s clear national interest. The same goes for shelving the cap‑and‑trade bill now before the Diet, which would impose an economy‑wide ceiling on CO₂ emissions.

Instead, Japan should expand its imports of fossil fuels from the U.S.

Japan currently spends ¥27.4 trillion a year on fossil‑fuel imports, yet only ¥1.4 trillion of that originates in the U.S.

Historically, the U.S. exported little energy, but the shale revolution has made it the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas. The U.S. also holds the world’s largest proven coal reserves, and recent administrations have encouraged coal exports.

Buying more U.S. fossil energy would let Japan cut its trade surplus dramatically. Prices and contract terms, of course, would have to be negotiated carefully; projects such as the oft‑discussed Alaska LNG development warrant case‑by‑case scrutiny.

Beyond economics, sourcing energy from the U.S. would enhance Japan’s energy security. Resource‑poor Japan relies on imports for virtually all of its fossil fuels. Receiving supplies from its sole treaty ally—one with formidable naval power—would be invaluable in a crisis such as a Taiwan contingency. With its own interests at stake, Washington would undoubtedly ensure that tankers reach Japan.

If Japan redirected even one‑fifth of its fossil‑fuel purchases to the U.S., those imports would total ¥5.5 trillion a year—an increase of ¥4.1 trillion over current levels and enough to cut Japan’s ¥9 trillion trade surplus by roughly half.

Standing in the way is Japan’s current Basic Energy Plan, which calls for solar and wind to rise from about 10% of electricity generation today to 30–40% by 2040. If that roadmap is followed, demand for LNG and other fuels will fall, leaving little room to expand U.S. energy imports.

Japan should scrap the GX program that pours money into China and instead pivot toward U.S. energy. Doing so would shrink America’s trade deficit with Japan in a way that fully serves Japanese interests.