Media Global Economy 2023.03.13

What Japan Can Do to Contribute to Global Food Security

The article was originally posted on RONZA on February 14th, 2023

This column is a modified version of the original announcement.

Japan will host the G7 Summit in 2023. Grain prices have soared, primarily owing to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and developing countries in the Middle East and Africa are suffering from a food crisis. Against this backdrop, food security will be a major topic of discussion at the summit. Several embassies of G7 countries in Tokyo have already expressed their interest in hearing my views. This paper will examine how Japan can contribute to global food security.

As the host country of the summit, Japan is closely connected with food security. The world, especially developing countries, faced a food crisis in 2008 as well. Food security was a major topic of discussion at the Hokkaido Toyako Summit, where Japan acted as the chair. The crisis was caused by the U.S. policy to use a huge amount of corn for the production of ethanol, a substitute for gasoline. Corn was not only used for food and feed, but also as a raw material for energy. The U.S. policy increased demand for grain, and accordingly world grain prices nearly tripled. People starved in the Philippines and other countries, where the price of imported rice surged. The U.S. was criticized by the world. However, seeing U.S. farmers booming thanks to price hikes, the Bush administration was not willing to change its policy. The U.S. prioritized winning the agricultural vote over starvation in developing countries.

Incidentally, out of all foodstuffs, this paper will focus on grains and soybeans. The reason is that these are important agricultural products as they are not only a major source of calories for people but also feed livestock, thereby indirectly providing people with milk, meat, and other livestock products (although little rice is used as feed). Among grains, rice, wheat, and corn are the most produced and consumed, and are referred to as the three major grains. In addition, soybeans classified as “oilseeds,” are also included in “grains” below.

Food crisis caused by physical inaccessibility

There are two types of food crisis.

One type is a crisis that occurs when food is not physically accessible. In Mariupol, which fell under the control of the Russians, starvation occurred because food from the Ukrainian government and the Red Cross did not reach the citizens. Food did not reach the affected areas for a while after the Great East Japan Earthquake, either.

In developing countries, even when grain prices are not rising, conflicts, such as the civil war in northern Ethiopia, often result in the physical unavailability of food. Furthermore, unless transportation infrastructure is developed, aid supplies from foreign countries cannot reach villages in remote areas even if they arrive at ports.

Such crises do not occur in exporting countries where political conditions are stable such as the U.S., Australia and the EU, except in the case of local disruption of transportation networks due to disasters like the Great East Japan Earthquake. By contrast, even in developed countries such as Japan, which depends on imports for the majority of its food, if the sea lanes are destroyed and imports are disrupted owing to an emergency in Taiwan or other reasons, the entire country would suffer from a serious food crisis.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) also cites cases in which a food crisis would occur in Japan, such as a massive crop failure in the U.S. and other exporting countries. However, when a major rice crop failure caused the Heisei Rice Riots, rice production decreased by only 26%. The U.S. exports 60% of its wheat production, and a crop failure that reduces production by 60% is unlikely to occur. It is also unlikely that other exporting countries such as Canada, Australia, and the EU will experience a major crop failure at the same time. We often hear news of abnormal weather that causes poor harvests in some regions of the world, but there are simultaneously other regions which enjoy rich harvests, offsetting the impact on worldwide production. Prices and supply and demand of grains should be considered from the perspective of global supply, and we should not see a bad harvest in a particular country as a problem. If the U.S. cannot export, you should import from Australia.

To begin with, global supply is on an upward trend. Even during exceptional crop failures, production is reduced by only a few percent. Even if world exports decrease and prices skyrocket, Japan will not become unable to buy grain. Japan faced no food crisis even in 1973, when grain prices surged to their highest level in 80 years in real terms. At that time, world grain production slid only 3%.

The same is true for port strikes. There is no possibility of strikes happening in the U.S., Canada, Australia, and the EU at the same time and disrupting Japan’s agricultural imports.

The MAFF may find all possibilities of food crises, but a food crisis is most likely to occur in Japan when a military conflict breaks out around the country, or Japan itself becomes involved in such a conflict. And we cannot say that it is unlikely. If China invades Taiwan, it cannot land without securing control of the skies. If China thinks that bombing by the U.S. Air Force would make it impossible to land, it might attack U.S. military bases in Japan. If that happened, Japan would be drawn into the conflict, and imports would be completely disrupted.

Of course, there are a variety of situations depending on the degree and the length of the disruption, but an armed conflict breaking out nearby would certainly affect the sea lanes, including shipping companies’ refusals to transport goods to Japanese ports.

Japan’s food security must be considered as an integral part of its military security. The same goes for energy. The problem with Japan is that there is no organization within the government that analyzes, judges, and handles these issues in a comprehensive manner. The vertically segmented administrative system cannot prepare for contingencies. We cannot mobilize the military unless logistics such as food and energy are prepared. Military security is not an issue that the Ministry of Defense alone can deal with.

Food crisis caused by inability to buy

Although it does not happen in Japan, people in developing countries sometimes suffer from hunger due to economic inaccessibility of food, i.e., the inability to buy food.

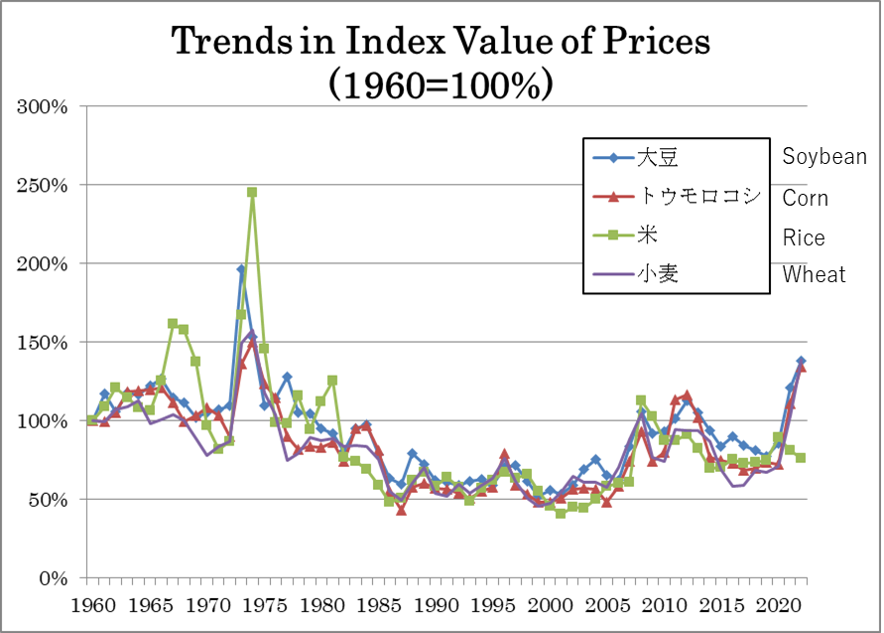

The real price of grains, excluding price fluctuations, has been on the decline for the past century. This is because the increase in grain production has substantially outpaced population growth (compared to 1961, population has experienced a 2.5-fold increase, rice 3.5-fold, and wheat 3.4-fold as of 2020). The following chart shows the change in real prices with 1960 as 100. The current price of grain, which is said to be the highest in history in nominal prices, is still considerably lower in real prices than it was in 1973.

Grain production is expected to increase thanks to innovative technologies, including genome editing and cultured meat, together with conventional crop improvements. Even if the population reaches 10 billion in the future, there is no need to worry that grain prices will remain permanently high and people will not be able to afford it. This is especially true in high-income countries like Japan.

However, there are times when the supply-demand balance collapses and prices surge owing to unexpected circumstances, such as in 1973 and 2008, and recently in 2022. The sharp increase in prices is called a “pike” because it sticks out like a pike.

This is difficult to predict, no matter how sophisticated the global food supply-demand model is. The 1973 crisis was caused by massive purchases of grain by the Soviet Union. The 2008 crisis was triggered by a shift in U.S. agricultural and energy policy that increased the use of corn for ethanol production. The cause of the 2022 crisis was the invasion of Ukraine by Russia’s Putin. No one can predict these events. Unpredictable factors cannot be included in the model. However, the international community must deal with the consequences of such events, i.e., the pikes.

People in developing countries often spend about half or more of their spending on food, especially grains and other agricultural products. Although statistics are not available for many countries, particularly those in Africa, the share of food in consumption expenditures in the countries whose data are available is 42% for each of the Philippines and Pakistan, 43% for Kazakhstan, 52% for Kenya, and 59% for Nigeria (2016, United States Department of Agriculture). These are averages, so it means that there are people in these countries whose share of food in consumption expenditures is higher.

For these people, if grain prices more than double, they will not be able to afford bread and rice, resulting in hunger. It is this type of crisis that is now occurring in the Middle East and sub-Saharan countries as wheat prices are rising sharply.

Response to Crisis Caused by Inability to Buy and Japan

There are two countermeasures to this type of crisis, although they take time.

The demand-side measure is to support the economic development of developing countries to increase their incomes. Meanwhile, the supply-side measure is to increase the supply of food and agricultural products to lower their prices. In particular, the international community has provided support for food production in developing countries. The United Nations has traditionally addressed this type of crisis, by undertaking measures to combat poverty (to increase income) and to boost food production.

In Japan, this type of crisis, i.e., a crisis caused by the inability to buy because there is no money, does not occur. In 2008, no one in Japan should have felt unable to buy food. At that time, the consumer price index for food inched up only 2.6% in Japan. Of the money Japanese consumers pay for food and beverages, 87% goes to processing, distribution, and food service. Only 2% of the money is spent on imported agricultural and fishery products. Even if the price of imported grains, only a part of the expense, grew threefold, it would have little impact on overall spending. This structure of food expenditures is common in Europe, the U.S., and other developed countries.

When grain prices rise, some people prompt fears of a looming food crisis by saying that it is caused by a Chinese eating spree or that Japan will be beaten by China in the buying competition. Quite a few of these people want to use the food crisis that is occurring in the world as an excuse to call for increased domestic agricultural protection. But even if Japan loses out to the Chinese in buying high-end tuna, it will not lose out to the top three wheat importing countries, Indonesia, Turkey, and Egypt, in buying wheat.

Food security to be discussed at the G7 Summit

Food crises caused by physical inaccessibility are often linked to civil wars, international wars, and other military conflicts. In order to prevent this type of crisis from occurring, we must prevent military conflicts. If a conflict actually breaks out and sea lanes and other logistical routes are cut off, the affected countries must deal with the problem themselves. When sea lanes to Japan are destroyed and imports are disrupted, Japan has no choice but to tap stockpiles and increase domestic production. There is nothing that international organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) can do.

Therefore, the food crises that will be discussed at the G7 Summit will be mainly those caused by economic inaccessibility. The fundamental measures against this type of food crises are to raise incomes and increase food production in developing countries, as described above. However, these are long-term challenges and measures, not solutions to the immediate food crisis.

Are regulations against export restrictions imposed by exporting countries effective?

For this reason, food aid has been provided in the form of direct delivery of grains and other foodstuffs as a short-term solution. Examples of food aid include those implemented through the Food Aid Convention under the International Grains Agreement and the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate. In 2022, an arrangement was made so that wheat exports from Ukraine would not be interfered with.

With that being said, in most cases, food provided for emergency assistance is excess agricultural products no longer needed in exporting countries (Japan is currently considering disposing of excess nonfat milk powder as food aid). When there is an excess of supply, international prices remain low; when there is a shortage of supply, international prices are rising. This leads to the following problem: when international prices are low and developing countries can afford to buy enough, food aid increases; and when there is a real crisis, the amount of aid decreases.

As a similar case, from 1995 through 1997 when international grain prices rose, the EU imposed an export tax (the difference between the higher international price and the lower price in the region) in order to supply grain to consumers and processors in the region at a lower price than the international price. During the Uruguay Round of negotiations, the EU argued that it was supplying cheap food to developing countries through export subsidies, but it prioritized supplying the internal market through export taxes when international prices rose and food became unavailable for developing countries.

One possible way to tackle the world food problem on the trade front is to regulate export restrictions imposed by exporting countries. During the GATT Uruguay Round of negotiations, Japan, as an importing country, proposed that export restrictions imposed by exporting countries should be regulated for the sake of food security, and this proposal was adopted and contained in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture under Article 12. As a negotiator, I too believed that such regulations would be effective for the food security of importing countries. In addition, a statement was issued at the 2022 WTO Ministerial Conference confirming the importance of regulations against export restrictions.

However, as I developed a deeper understanding of global agricultural trade and the realities of countries that imposed export restrictions, I have found that Article 12 of the WTO Agreement on Agriculture is of little use. The reasons for this are explained in detail in “Can the WTO Solve the Food Crisis?” (June 23, 2022), but I would like to briefly explain them again here.

The first reason is the reality of countries that impose export restrictions.

It was widely reported that more than 20 countries were restricting exports in 2022 as well, but none of these countries, with the exception of India and Vietnam with regard to rice, have any impact on world trade.

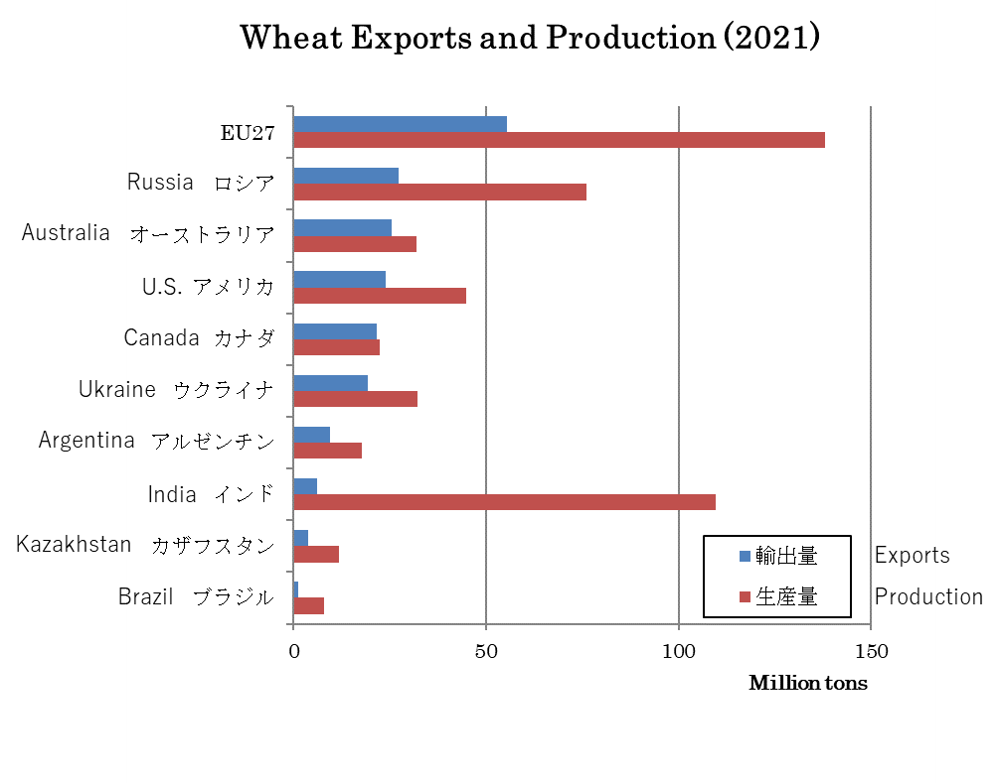

India, the world’s second largest wheat producer, imposed restrictions on wheat exports, which was reported as causing a global food crisis. It is true that India’s wheat production exceeds 100 million tons. However, exports were 930,000 tons in 2020; and despite a significant increase, it remained only 6.09 million tons in 2021. This is due to the large population and domestic consumption. Also, because of the large level of production, exports will increase significantly when there is even a slightly good harvest, and decrease significantly when there is a poor harvest. It is an unstable exporter. In contrast, the world’s total trade volume is about 200 million tons, while the U.S., Canada, and Australia export 20 to 30 million tons each. Even if India bans the export of wheat, it will not have a considerable impact on global wheat supply and demand. Incidentally, China is the world’s largest producer with 140 million tons, but exports only 4,000 tons.

Second, most of these countries are developing countries. Left to free trade, wheat is exported from countries where the price is low to international markets where the price is higher. When this happens, domestic supply would decrease and domestic prices would rise to the same level as international prices. Even a country which has traditionally been a wheat importer will export wheat, if wheat is produced domestically. Therefore, even importing countries may restrict exports.

Poor people, who spend most of their income on food, will not be able to afford food when food prices double or triple, and suffer from hunger. Countries that restrict exports tried to prevent this. In other words, an exporting country imposes export restrictions only to defend its own citizens against starvation. The international community cannot insist that such a country should export even if it leads to starvation in its own country.

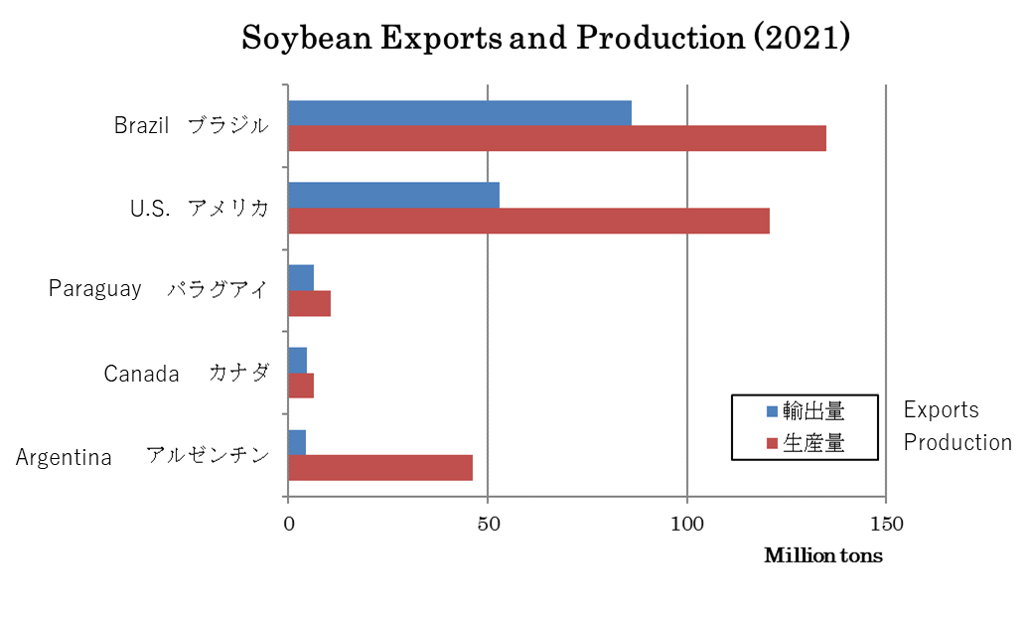

On the other hand, major exporters of wheat, corn, and soybeans, such as the U.S., Canada, Australia, Brazil, and Argentina, do not impose export restrictions. Accordingly, there are no cases where Article 12 of the WTO Agreement on Agriculture is applied.

First, incomes in these countries are high, so few consumers are affected by higher grain prices. In developed countries, 90% of food expenditures are for processing, distribution, and food service, with only a small amount spent on agricultural products. Even if the price of grain, which is a part of such spending, rises, the impact on overall food spending will be negligible. Conversely, producers benefit from higher prices.

In addition, these countries export wheat, which accounts for 60-80% of their production. Without exports, domestic markets would face oversupply of grain and prices would plunge. Meanwhile, other exporting countries would benefit because prices rise on the international market owing to a supply shortage. Export restrictions do not benefit the exporting countries.

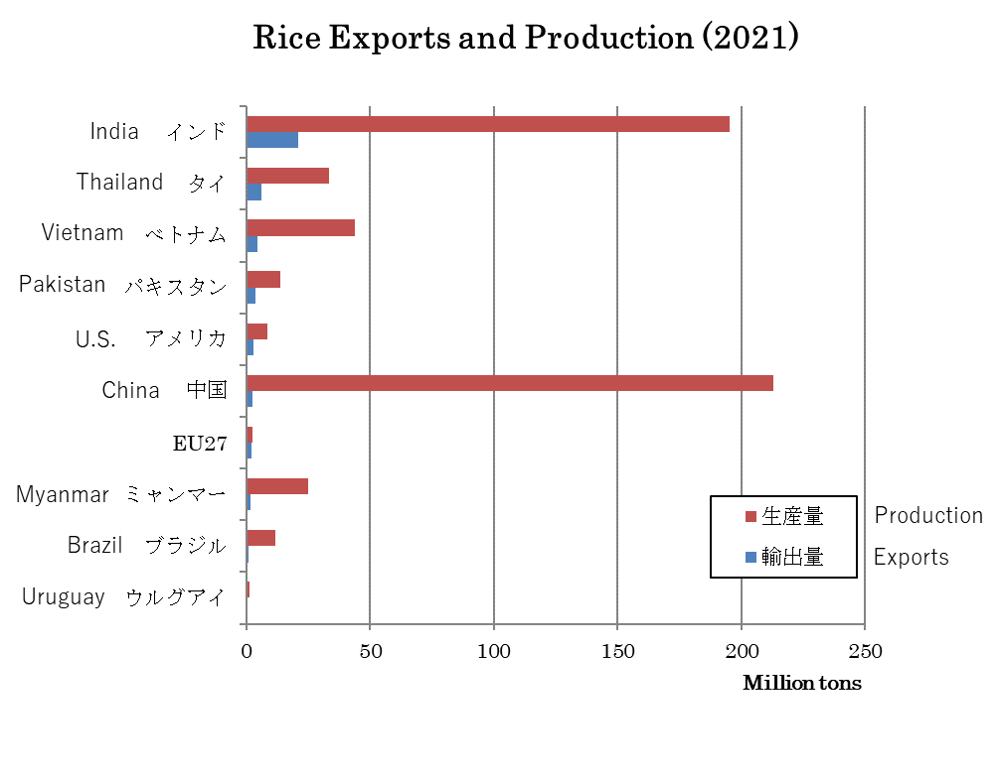

(Source) Compiled by the author based on FAOSTAT.

A major exporter like the U.S. would never restrict exports; and even if a developing country like India restricts exports, we cannot tell it to export when its citizens face starvation. International regulations against export restrictions have these limitations. In order to address the global food security issue, it is more important to solve the poverty problem and boost food production in developing countries.

Global contribution Japan can make

However, rice is the only exception among grains. The world’s three largest rice exporters are India, Vietnam, and Thailand. These are not developed countries. With the exception of Thailand, which has relatively high incomes, India and Vietnam imposed export restrictions when grain prices soared in 2008.

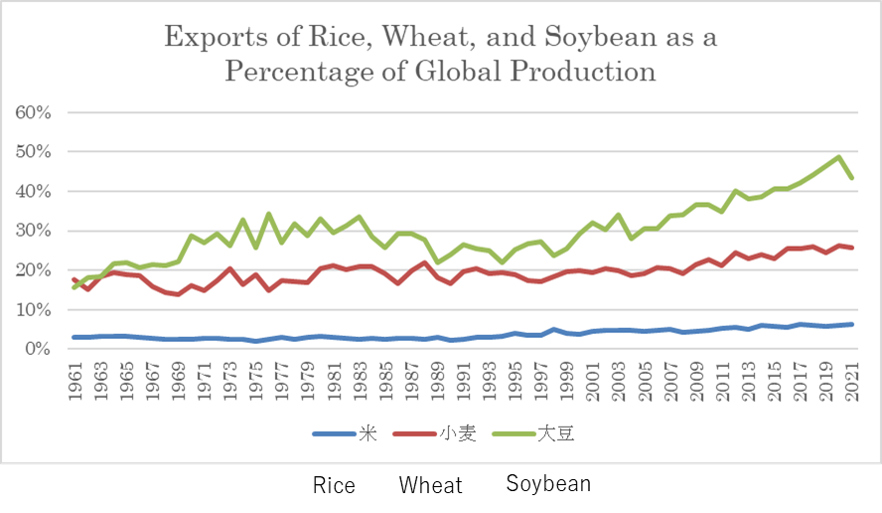

In addition, unlike in the case of wheat and other crops, rice exported accounts for an extremely small proportion of rice produced. Only 6% of rice production is exported, while the comparative figures are 26% for wheat, and 43% for soybean, indicating that the rice market is a thin market. In terms of export volume, rice is only 50 million tons, a quarter of the 200 million tons of wheat. Consequently, if India (which exports 20 million tons of rice) and Vietnam (5 million tons), two of the three largest exporters with low per capita income, restrict their exports, the world trade volume would be halved and prices would rise sharply (figures are for 2021).

Even in these countries, exports as a percentage of production are extremely low, so even without export restrictions, a small decrease in production would result in a large decrease in exports. In the case of India, if consumption remained the same, a 10.7% decline in production would result in a 100% drop in exports. The rice trade is extremely volatile.

(Source) Compiled by the author based on FAOSTAT.

Furthermore, many of rice importing countries are developing countries as well. In 2008, rice importing countries, such as the Philippines, suffered a great deal of damage from export restrictions imposed by India and Vietnam. Of course, it was politically difficult to tell India and Vietnam, developing countries with low income levels, to stop export restrictions for the Philippines since they were restricting exports in self-defense.

That is to say, among grains, rice has a serious problem from the perspective of food security.

Nevertheless, there is only one country in the G7 that can contribute to solving this problem. That is Japan. Japan, which has only looked at the domestic market, has been reducing rice production for more than 50 years through its rice acreage reduction policy. Now domestic production has been curtailed to less than 6.7 million tons. However, the potential production capacity is 17 million tons. Why not stop the reduction of rice acreage, consume 7 million tons domestically, and export 10 million tons? While the Japanese government is promoting the export of agricultural products, the most promising export item is Japan’s delicious rice.

If Japan exports 10 million tons of rice, world rice trade would jump 20% to 60 million tons. Thailand and Vietnam export only 5-6 million tons each. Japan will become the world’s second largest rice exporter after India. Moreover, if 60% of its production is exported, the export volume will not tumble even if production decreases, unlike in the case of India. A 10% fall in production would result in only a 17% decline in exports. Japan would be a stable rice exporter. Is this not a valuable contribution that Japan, mizuho no kuni or the “land of abundant rice,” can make to the rice trade, which is the most vulnerable part of the grain trade from the viewpoint of food security?

If Japan’s sea lanes would be destroyed and physical access would become difficult, the country would not be able to export. In the event of such an emergency, if the 10 million tons of rice exported in peacetime would be consumed domestically, it could prevent 120 million Japanese people from starving. This would serve as a free stockpile with no financial burden.

Contributing to global food security would lead to food security for Japan. This is exactly what “He who gives to the poor lends to the Lord” means, is it not?

Yet, the MAFF, under pressure from the Ministry of Finance (MOF), is striving to cut rice production with the aim of slightly reducing rice production subsidies, by encouraging farmers to convert rice paddies to fields for wheat and soybean production, which is a waste of taxpayer money.

At present, consumers are paying higher prices than international prices for domestically produced wheat and soybeans. In addition, despite 230 billion yen currently spent on the promotion of wheat and soybean production, only 1.3 million tons of wheat and soybeans are being produced. If you have 230 billion yen, you can import and stockpile roughly 7 million tons of wheat, which is more than the annual consumption of wheat in Japan. When a crisis occurs, there is a big difference between having only 1.3 million tons and as much as 7 million tons.

Even without doing so, if only the reduction of rice acreage were abolished, a financial burden of 350 billion yen would be eliminated. In addition, Japan would be able to export a large amount of rice and cut the trade deficit. In times of crisis, there would be 10 million tons of rice reserves.

Vanishing rice paddies also means the loss of their multifaceted functions, such as recharging water resources and preventing flooding. There is probably no one left in either the MAFF or the MOF who can see the big picture. It is a pity that Japan’s administrative organization seems to be deteriorating.

Diffusion of APTERR created by Japan

In order to deal with the food crisis, we must stockpile food and increase food production.

At a meeting of the Agriculture Ministers of ASEAN countries and three countries of Japan, China, and Korea held in Laos in 2002, Japan proposed a rice stockpiling system to cope with natural disasters and other emergencies in the East Asian region. I participated in this meeting as a negotiator. After an experimental period, the ASEAN Plus Three Emergency Rice Reserve (APTERR) has been implemented since 2012, and rice has been provided to the Philippines, Cambodia, and other countries in times of crisis under this program.

This is a regional interstate food security system created by Japan’s initiative. Could we not propose this idea and mechanism to regions where food security is an issue? For example, we could propose the creation of a wheat stockpiling system in Africa to the U.K. and the EU (the former sovereign nations) plus the U.S.

This would also be a major contribution by Japan to global food security. In addition, it would provide a good opportunity to demonstrate at the G7 Summit that Japan has made steady efforts towards stability in the Asia-Pacific region.