Media Global Economy 2023.01.26

Six actions the government should take to allow us, the public, to take back agriculture

Straighten out Japan’s agricultural policy and administration by taking advantage of the ongoing process of revising the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act

The article was originally posted on RONZA on December 9th, 2022

The previous article discussed what basic principles the government should abide by to achieve the goal of securing and improving such benefits of agriculture as food security and multifunctionality for the public as a whole (“Time to overhaul Japan’s post-war agricultural policy and administration,” December 1, 2022). This article, the last of the series of my discussions on how the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act (“the Basic Act”) should be revised, examines how this goal should be achieved. Japan’s agricultural policy and administration today have made serious mistakes in terms of not only basic principles but also policy instruments.

Japan’s agricultural policy lags far behind global standards

To what extent the farming sector of a country is protected can be measured with the Producer Support Estimate (PSE), developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The PSE is the sum of the taxpayer burden or the fiscal burden to maintain farmers’ income, and the consumer burden, which is the difference between domestic and international prices multiplied by domestic production. The consumer burden represents the amount of income transferred to farmers by consumers paying high domestic prices to farmers instead of low international prices. The equation: PSE = the fiscal burden + the difference between domestic and international prices × domestic production.

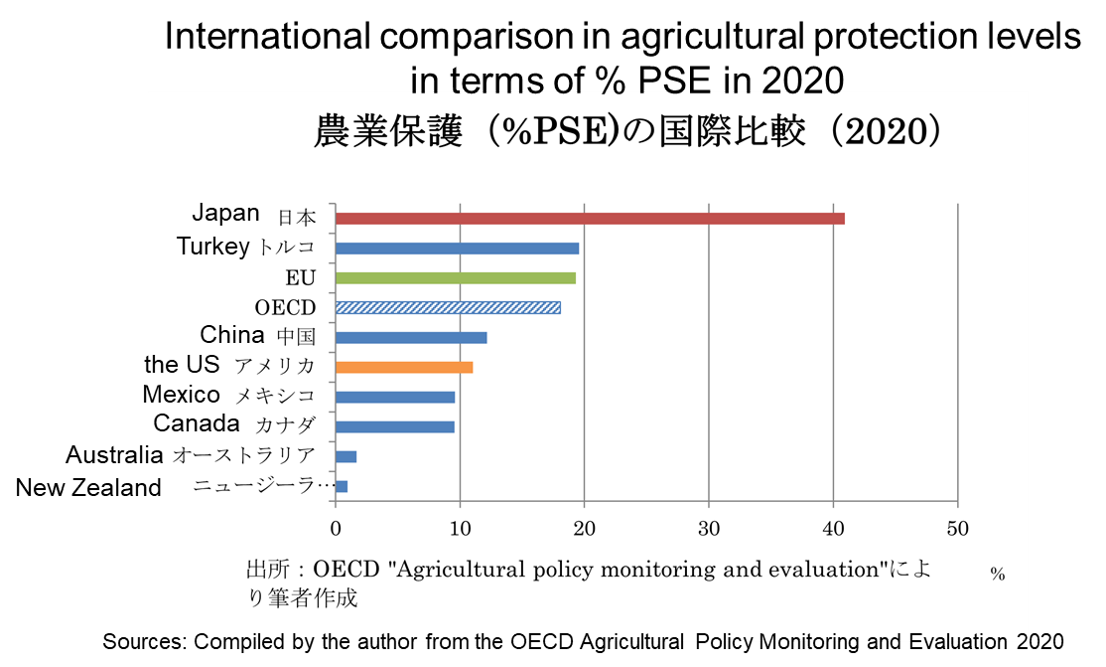

The percentage PSE (% PSE) or the ratio of the PSE to the value of total gross farm receipts was 40.9% for Japan as against 11.0% for the US and 19.3% for the EU as of 2020. In other words, some 40% of farmers’ income in Japan comes from policy measures designed to protect agriculture.

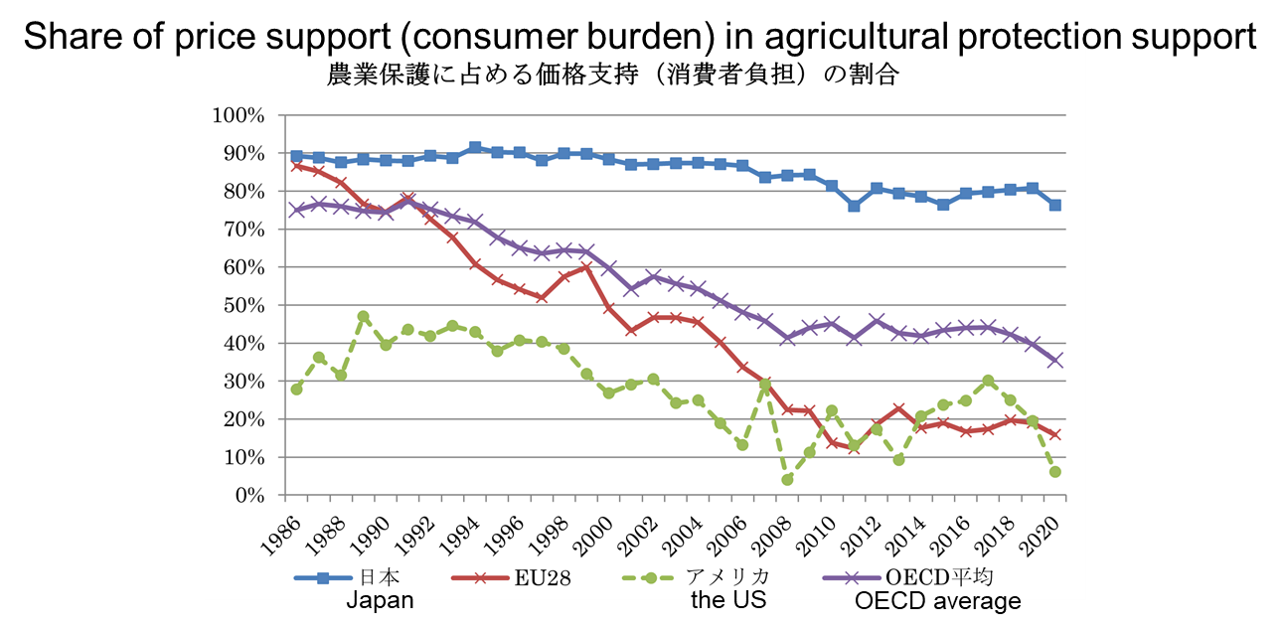

On top of that, Japan’s agricultural protection support is characterized by an overwhelmingly high percentage of consumer burden. A look at the breakdown of PSE for countries shows that the percentage of agricultural protection support that was borne by consumers in 2020 was 6% for the US, 16% for the EU, and 76% (or some four trillion yen) for Japan. While western countries have shifted from price support to direct payments, Japan’s agricultural protection policy remains centered on price support. With domestic prices greatly exceeding international prices, Japan needs to impose high tariffs on imported products.

Compiled by the author from the OECD Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2020

Politicians in the agricultural policy triangle described Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations as a “battle for the national interest.” That national interest turned out to be the maintenance of protective tariffs on agricultural products. What the tariffs protect is the high prices of domestic agricultural products, i.e., food. The high prices protect farmers and impose a burden on consumers.

As far as Japan is concerned, the amount paid by consumers for agricultural protection exceeds the PSE, which is merely the gap between domestic and international prices multiplied by domestic production. This is because Japanese consumers also pay high tariffs on imported farm products to maintain high prices for domestic products as in the case of wheat and beef. In comparison, the PSE largely represents the financial burden on the public for the agricultural product exporters of the US and the EU, where the public bear little burden due to small imports and low tariffs.

Japan addresses market distortions by fiscal means

Price support is not the only means to guarantee farmers’ income. Both the US and the EU provide such guarantee with direct subsidies to farmers while letting the market determine the prices.

Economists around the world agree that direct payments prove to be more effective than price support. (I do not know whether members of the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies are among them.) Price support is aimed at guaranteeing prices higher than those that would be determined by the market. It decreases demand and increases supply, resulting in excessive supply that would not happen in the market, where supply and demand are balanced out. Japan created large amounts of surplus rice under the food control system, whereby the government purchased rice from farmers at high prices. Such surpluses of agricultural products used to be created in the EU as well. To eliminate such surpluses, Japan implemented the rice acreage reduction program, which involves granting subsidies. The EU, on the other hand, sold them on international markets using subsidies.

In short, price support gives rise to a market distortion called surplus. Disposing of such surpluses strains government finances. Direct payments do not cause a surplus. The EU noticed this problem, and in 1993, shifted from price support to direct payments, although export subsidies incurred wrath and criticism from the US and other countries. Both Japan and the EU granted subsidies, but they differed in that the former used them to reduce production while the latter used them to boost it. The EU’s subsidies were far better from the perspective of food security.

Japan should have shifted to direct payments when it abolished the food control system in 1995. But the country opted to keep rice prices high by reducing rice supplies through acreage reduction. What Japan is effectively doing is using the acreage reduction program to avoid any possible surplus. It was unfortunate for Japanese policy authorities that, unlike the EU, Japan had a pressure group called the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA), which had developed thanks to high rice prices.

Some agricultural economists argue that western countries give more generous protection. They cite a smaller taxpayer burden or lower direct payments in Japan. I suspect that the argument that Japan is less protective of the agricultural sector would not be entertained by agricultural economists in the OECD or even in the world. Surprisingly, however, the Agricultural Economics Society of Japan (AESJ) seems to have some supporters of this peculiar argument. I believe that some agricultural economists in the AESJ disagree. Yet refraining from rocking the boat seems to be a virtue of the AESJ. My advice is, “do not believe what experts say as far as it concerns Japanese agriculture.”

Action 1: Transform agricultural policy and administration that impose a burden on consumers

Article 2, paragraph (1) of the Basic Act states:

“Given that food is indispensable for maintaining human life and important as a basis for a healthy and fulfilling life, high-quality food must be stably supplied into the future at a reasonable price.”

Paragraph (3) of the same article provides that “food must be supplied [...] while promoting the improvement of agricultural productivity.”

In short, the Basic Act calls for supplying food at prices that are as affordable as possible. In other words, it gives consideration to low-income consumers.

However, the “agricultural policy triangle,” which is made up of the JA, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), and the lawmakers of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who represent agricultural interests, tries to beef up the acreage reduction program in order to further reduce rice production and raise rice prices. Even when the prices of almost everything are rising, the Japanese government is doing the opposite of taking price stabilization measures with regard to rice, which is thought to be more fundamental than wheat as a national staple food.

The voice of the needy does not reach the MAFF panel

Members of the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies, which has been set up within the MAFF, include a consumer representative, who is from a group largely made up of wealthy housewives. The Council does not have a representative of the needy, although ongoing rises in food prices are making it more difficult for food banks for the needy to procure food.

This consumer representative sympathizes with the idea of domestic production for domestic consumption as advocated by the JA, saying that domestic products are preferable even though they may be sold at relatively high prices. Yet some people cannot afford to buy enough food at the current prices, let alone “relatively high prices.” The voice of the needy does not reach the Council.

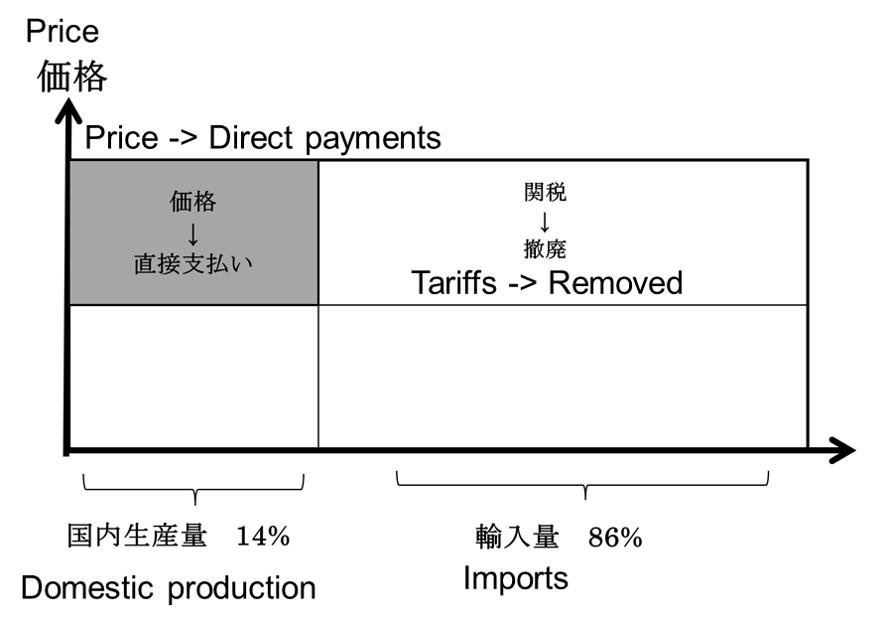

The government has been imposing a high tariff on foreign-produced wheat, which accounts for 86% of wheat consumption in Japan, to maintain the high prices of domestically-produced wheat, which accounts for only 14%. This tariff, or a surcharge collected by the MAFF to be more precise, has meant that Japanese consumers have no choice but to buy high-priced bread and udon noodles. The government should shift to the policy of compensating for the gaps between the prices of domestically-made products and those of foreign-made products by granting subsidies directly to farmers from government finances. Japanese consumers would benefit greatly from this policy because it would obviate their need to shoulder the extra burden associated with foreign as well as domestic products. The policy could reduce the burden on Japanese consumers while providing the same level of protection to the domestic agricultural sector.

Action 2: Just abolish the acreage reduction program

This is a step the MAFF can take without effort.

Rice acreage reduction is an abnormal program in that it grants subsidies, which entail the taxpayer burden, to raise rice prices, which increases the consumer burden. This contrasts sharply with public health care programs, in which government spending allows the public to gain affordable access to necessary goods and services. Japanese consumers shoulder a double burden both as taxpayers and as consumers. Raising the price of rice, the national staple food, is more regressive in nature than the consumption tax. Acreage reduction is the exact of opposite of what is embodied by the Japanese term keisei saimin or the principle of governing a nation and providing relief to people. [This term has given rise to the term Keizai, the Japanese translation of “economy.”] It is the worst policy from the perspective of economics.

All the government needs to do is just abolish the acreage reduction program. That will obviate the need for acreage reduction subsidies, which amount to 350 billion yen. The losses that business farm households will incur due to a fall in rice prices can be compensated for with direct payments totaling some 150 billion yen. Part-time farm households who depend on salaried income will not need such direct payments to support their income.

Rice prices will fall. Small-scale, part-time farm households will stop farming and begin to lease their farmland to business farm households. Direct subsidies to business farm households will help them pay the rent, with the result that farmland will be smoothly concentrated in their hands. Resultant larger farm sizes will reduce the cost for business farm households, pushing up both their revenue and the rent they pay to their landlords, former part-time farm households.

The concentration of farmland will revive rural areas

The net income for rice farm households with an acreage of less than one hectare, which represents the average scale for all prefectures except Hokkaido, is almost zero or below that level. The collective net income of such farm households, even if they total 20 or 40 in number, amounts to zero. Zero times 20 or 40 equals zero. But if, say, 20 hectares of farmland in a community is cultivated by one farmer, he or she will earn 15 million yen in net income. Part of this income will be distributed among the households who lease their farmland to him or her as a rent. This will better benefit the entire community.

Just as the rent to the owners of buildings is partly used by them to repair their buildings, the rent paid for farmland is partly used by the landlords to maintain and improve local farming infrastructure, including farmland and canals. Landlords have their own role to play.

The rent paid by creditworthy tenants (or farmers) allows the owners of the buildings (or farmland) to carry out repair works. Unless such a trusting relationship is established, rural communities are bound to decline. Agricultural structural reform is needed not least to revitalize rural areas.

Such reform will not only help Japan’s rice industry; it will also help low-income consumers with lower rice prices. As far as the food sector is concerned, nothing beats the abolition of the acreage reduction program as a price stabilization measure.

Action 3: Use the private economy to reduce the burden on the public

When rice prices fall, Japan’s agricultural administration buys rice in the market to keep them high or make up for any gap in prices for farm households. In 2019, the government introduced an insurance scheme designed to compensate for losses in farmers’ income. The program makes up for a drop in farmers’ revenue due to falling prices or natural disasters.

Futures trading provides a means for producers to mitigate the risk of price fluctuations and conduct business in a stable manner. For example, a farmer who has entered into a futures contract prior to planting for the sale of rice for 15,000 yen per bag (60 kg) can get 15,000 yen per bag in revenue by selling the harvested rice, even if the rice price plunges to 10,000 yen per bag during the harvest season due to a bumper crop or dwindling demand.

The JA is against future trading, saying that it will subject rice to speculative transactions, which in turn will result in price volatility. However, suppose speculative money causes the rice futures price to increase to 20,000 yen per bag. That would be a good thing for farm households. Suppose again that the futures rice price rises and farm households opt to cultivate rice without participating in the acreage reduction program. This may lead to a lower rice price during the harvest season. But farm households still can sell rice for the futures price, not for the lower price. If futures prices go up, producers will try to increase their production, thus reducing spot prices in the future. This will help stabilize the market. If rice prices are likely to soar owing to a poor harvest, distributors can conclude a futures contract for a lower futures price to hedge risks. Speculators bear the risks in the futures market in place of producers and consumers. The JA opposes rice futures trading because it will be unable to manipulate prices as they are determined on the market, not through negotiations with wholesalers as currently practiced.

Every time rice prices fell, the government bore the burden of compensating farmers. This is why farmers saw no point in participating in rice futures trading that had been introduced on a trial basis. They just stayed away. The agricultural policy triangle has not approved the full-fledged introduction of such futures trading, citing small amounts of rice handled. However, the function of hedging futures risks to stabilize prices will obviate the need for price compensation or the insurance scheme. The financial burden on the public will be reduced.

Action 4: Rectify policies that have distorted the market and invited wrongdoing

In 2008, a fraudulent distribution case came to light that involved stained rice.

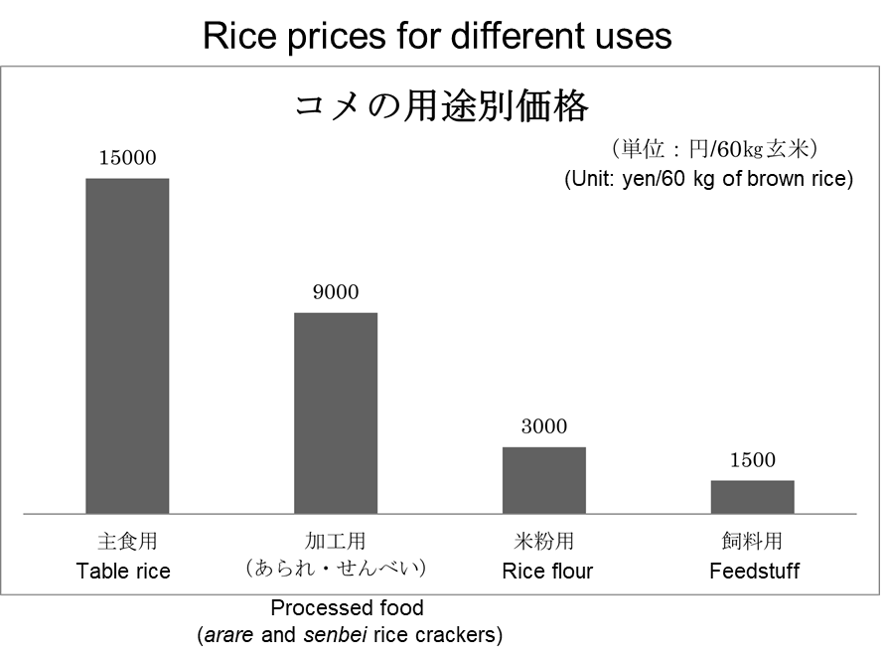

The MAFF sold imported “minimum access” rice that had become moldy as a paste material. Some food-related businesses bought this tainted rice for low prices and resold it as table rice for higher prices for profit. The stained rice, which amounted to 8,368 tonnes, was mostly sold through illegal channels. Rice to be used as a material for industrial paste is sold for around 10,000 yen per tonne. But rice to be processed into shochu distilled spirits, arare and senbei rice crackers, and others can be sold for 150,000 yen per tonne, while rice to be used as table rice can be sold for 250,000 yen. Such illegal sales of rice surely make a big profit.

The heart of the problem lies in the arrangement in which the government keeps the prices of table rice high under the acreage reduction program, sets the prices of rice to be used for other purposes at lower levels to create demand for such rice, and compensates for the gaps between these two types of prices with crop switching (acreage reduction) subsidies. In short, different prices are set for rice of the same quality depending on its use. The different-prices-for-one-product arrangement makes for wrongdoing. To prevent such wrongdoing, policies that distort the market should be rectified.

Source: Investigation by the author

One price for one product could be achieved if it were not for government intervention

Surprisingly, however, the MAFF maintained that it was no longer able to check fraudulent practices of distributing rice because the abolition of the food control system meant no regulations on rice distribution. Then the MAFF drafted the Rice Traceability Act (formally known as the Act for Keeping Transaction Records and Transmitting Place of Origin Information Relating to Rice and Rice Products Trade) in 2009. In short, the MAFF took advantage of the stained rice case to preserve its organization. After all, the Rice Traceability Act proved to be ineffective. In 2013, a rice trader called “Mitaki Shoji” illegally sold rice produced in China and rice for processing purposes as table rice.

Any economic policy should essentially get to the root cause of the problem it is designed to address. The problem here is that rice comes in different prices with table rice being priced high. If the government wants to expand the demand for rice, it should increase the demand for rice exports by abolishing the acreage reduction program to reduce prices. If the government ceased its intervention, one price for one product would result.

The different-prices-for-one-product arrangement also exists for raw milk. The government should cease to intervene in the raw milk market to realize one price for one product. This will allow Japanese milk producers to export raw milk in response to the growing demand for milk for direct consumption in Asia.

Action 5: Boost the production and exports of rice not least to make Japan self-sufficient in food

A major factor for Japan’s dwindling food self-sufficiency is that the government substantially raised the prices of domestically-produced rice, resulting in lower consumption, while it artificially maintained the prices of imported wheat, barley, and naked barley, resulting in high consumption of these grains. Around 1960, rice consumption was more than three times larger than wheat consumption in Japan. Now both are almost the same. The consumption of wheat, barley, and naked barley combined has surpassed rice consumption. Now, the staple food for the Japanese may be imported wheat and barley rather than rice.

This is the result of the government treating domestically-produced rice badly and foreign-produced wheat and barley favorably. Currently, Japan imports eight million tonnes of wheat and barley after reducing rice production by five million tonnes. Because high rice prices reduced the demand for rice, the government put the acreage reduction program in place to keep rice prices high [to make up for the losses for rice farmers].

Japan has maintained the target of raising its food self-sufficiency rate to 45% for more than two decades from 2000. Yet the rate has been falling from 40% in 2000. It stood at 38% in 2021 as opposed to 79% in 1960. Rice supported more than half of Japan’s food self-sufficiency both in 1960 and 2021. In other words, the drop in food self-sufficiency is largely attributable to reduced rice production.

Stop acreage reduction, and Japan’s self-sufficiency will overshoot the target

Food security can be best achieved by stopping acreage reduction to boost the production and exports of rice. This approach will allow Japan to export surplus rice in peacetime and divert such rice to feed the Japanese public in times of crisis. The Japanese government uses public funds to stockpile rice and imported wheat for emergencies, but rice exports can serve as free stocks of rice for such purposes.

The export of rice means a higher food self-sufficiency as it cannot be done without production in excess of domestic consumption. If Japan used all its paddy fields to grow the type of rice whose yield per unit area is on par with that of Californian rice, it would likely be able to boost rice production to 17 million tonnes. Of the 17 million tonnes of rice produced in Japan, seven million tonnes would be consumed domestically and the remaining 10 million tonnes would be exported. Self-sufficiency in rice would be 243%.

Of the current food self-sufficiency rate of 38%, 20 percentage points come from rice and 18 percentage points come from other crops. Suppose three percentage points is lost from the 18 percentage points when rice acreage increases at the expense of the acreage of other crops. The food self-sufficiency rate will be 64% (20% × 243% + 18% − 3%), far exceeding the long-held target of 45%.

The agricultural policy triangle has used low self-sufficiency as a pretext for protecting the agricultural sector and securing budget allocations. Low food self-sufficiency is convenient for the triangle.

Rice is the best farm product for Japan

The government says that it will continue working to increase the production of wheat and soybeans. Yet the policy since 1970 of reducing rice acreage to promote switching to wheat and other crops has proved to be virtually ineffective. For its part, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) plans to grant subsidies for converting paddy fields to upland fields as it does not want to provide subsidies for reducing rice acreage.

However, rice is the best farm product for Japan. Rice is gluten-free and contains larger amounts of essential amino acids that cannot be synthesized in the body than wheat. On top of that, domestically-produced wheat is so low in quality and unstable in production that the flour-milling industry shies away from it. This contrasts to domestically-produced soybeans, which are in demand to produce fermented soybeans. Domestically-produced wheat has long been in surplus as Japan continues to import large amounts of wheat from other countries. The flour-milling industry must be worried that it might be further pressed by the MAFF to procure domestically-produced wheat.

The policy that the government should take is to stop acreage reduction and boost rice production. If the government wants to reduce its fiscal burden substantially, it should put an end to acreage reduction. Such action, however, would pitch the MOF squarely against the LDP. The MOF must have thought that if some paddy fields are converted to upland fields, it will not have to pay acreage reduction subsidies for the area thus converted. So the MOF went ahead with granting subsidies for such conversion, presumably thinking that this was the second best measure to reduce the fiscal burden on the government.

What a cunning scheme! The government is trying to make it difficult to produce rice, the best farm product in Japan. Paddy fields are much better than upland fields in terms of multifunctionality. Rice acreage reduction cannot be justified from the perspective of economics as well.

It is about time we sat down and discussed food security.

Action 6: Streamline Japan’s agricultural administration

Unlike its counterparts in western countries, the MAFF makes paternalistic interventions, setting detailed agenda items and giving attentive guidance and support. As if to reflect this, the agricultural measures taken by Japan are detailed and complex. The MAFF has some 100 divisions, each of which is responsible for many programs. These programs largely involve extremely small subsidies.

One can get a general picture of agricultural policies in western countries by reading relevant laws. Japan is different. It is often the case that specific programs or mechanisms are not mentioned in laws or government and ministerial ordinances based on relevant laws. Instead, the MAFF draws up a number of administrative documents that are lengthy and abstruse in the form of guidelines and instructions for each subsidy program. These documents cover such topics as the purpose, complex qualifications, application forms, application procedures, and program implementation reporting. They are sent to prefectural governments and organizations concerned.

Employees at local governments, which serve as subcontractors for the MAFF, have to do the following: peruse all these documents, making sure that agricultural groups and farms fully understand the purpose and system of each subsidy program, and assist them in applying for subsidies. Local government employees have put much time and effort into executing all these duties. In other words, the MAFF deprives local government employees of the time needed for them to formulate policies necessary for promoting local agriculture.

The MAFF develops a wide variety of subsidy programs chiefly to create jobs for its employees. A case in point is a program launched in 2012 to help would-be farmers to start farming. Program participants can receive an annual subsidy of 1.5 million yen each for up to two years during the period they receive training. After they start their own farms, they are eligible for an annual subsidy of 1.5 million yen each for up to three years. So each participant is eligible to receive up to 7.5 million yen in total. Also on offer is a loan program designed to support new farmers. It offers interest-free loans of up to 37 million yen (or 100 million yen if special approval is given) with a redemption period of 17 years and a grace period of five years.

What a generous treat!

Lack of consistent policies

These programs have achieved little success, however. This is simply because lavishly subsidized, program participants fail to make the effort or to discipline themselves for farm management. All the MAFF does is to provide money; it does not even try to assess the performance of these programs. It has no intention of terminating them.

Because discrete programs are developed on the division level, the MAFF is unable to implement consistent food and agriculture policies.

The MAFF has conducted agricultural civil engineering (infrastructure development) projects totaling some one trillion yen every year as public works projects. These projects are designed to improve paddy and upland fields individually owned by farm households. But these beneficiaries contribute to only 15% of or so of total project expenses. The MAFF’s explanation is that even if farm households make investments to cut costs, they will be unable to secure a return on such investment because resultant drops in the prices of their farm products benefit consumers but not themselves. The MAFF has used this logic to justify the practice of conducting farmland development, which should be private investment projects implemented as public works projects. Over the past 50 years, the government has spent nine trillion yen on the acreage reduction program, which is designed to prevent the prices of farm products from falling, as well as more than three trillion yen on disposing of surplus rice. All MAFF officials responsible for agricultural civil engineering projects want is to secure necessary budgets and implement these projects. This increases their chances of landing high-paying jobs at private or semi-government corporations in the industries under their supervision after their retirement in a practice known as amakudari [literally “descent from heaven”]. So they have no interest in other realms of agricultural administration.

A similar situation can be observed in the livestock sector as well. Huge amounts of fiscal funds have been invested to improve its price competitiveness, but the prices of livestock products have been on the rise. The government maintains the prices of livestock products in order to protect livestock farmers whose annual income averages up to 20 million yen depending on the type of animals they raise, at the expense of low-income consumers. To begin with, the government should levy taxes on the livestock sector, which exerts a tremendous burden on the environment, instead of subsidizing it. The vegetable, fruit, and flower sector enjoys quite low levels of tariff protection, and such tariffs will be abolished as a result of TPP negotiations. In addition, the sector is not eligible for generous subsidies, unlike the livestock sector, which depends much on feed from abroad. Yet the vegetable, fruit, and flower sector contributes more to the protection of farmland resources than the livestock sector.

Now, Japan’s agricultural administration constitutes a complex and contradictory system with its flawed logic. Isn’t it about time we revisited the goals of agricultural administration such as food security and multifunctionality and explored simply and logically consistent agricultural policy?

Food security and multifunctionality can be achieved only when farmland resources are well maintained. If that is the case, the government just has to do away with item-by-item agricultural policies and assorted subsidy programs for new farmers altogether and grant farmers a set amount of subsidy per unit of farmland to maintain the total farmland in Japan. Such a single direct subsidy embodies what the protection of agriculture should look like—an ideal that has been achieved after years of reform efforts by the EU.

“Why on earth should they [farmers] not be encouraged to help themselves?”

A motley assortment of subsidy programs has deprived farmers of their creativity and ingenuity. They have become reliant on agricultural authorities or help in times of need. The three prominent figures I introduced in the previous article—Kunio Yanagita, Tadaatsu Ishiguro, Tanzan Ishibashi—all respected one man. His name is Ninomiya Sontoku (1787–1856), an esteemed agricultural leader and philosopher. The three also stressed self-help.

Kunio Yanagita stated the following:

“Petty philanthropists in society often emphasize that the populace must be helped. As I see it, this constitutes a profound contempt for them. I argue back, “why on earth should they not be encouraged to help themselves?” Self-help, progress, cooperation, and mutual help are the main aims of industrialcooperatives.” (see Yanagita, Kunio, Saishin Sangyo Kumiai Tsukai [Up-to-date commentaries on industrial cooperatives], compiled in Teihon Yanagita Kunio Shu [Complete authoritative collection of Kunio Yanagita’s works], Vol. 28, p. 130)

What to plant on farmland—be it rice, vegetables, or grass—should be left up to the creativity and ingenuity of farmers; this is not something agricultural authorities should meddle in. The government should not grant direct subsidies to livestock farmers who depend on imported feed and use no farmland. Farmers who want land improvement or any other type of infrastructure development should finance such a project with direct subsidies they receive. If Japan’s agricultural administration was streamlined like this, technical MAFF officials responsible for agricultural civil engineering would no longer mount campaigns to secure budgets for public works projects in order to land high-paying jobs at general construction contractors after they leave the MAFF. The MAFF would be substantially streamlined in terms of both organization and personnel. Local government employees would not be bothered by the motley assortment of subsidy programs any more.

Current agricultural policy and administration in Japan are too complicated to understand; they serve MAFF officials and employees, not the public.

The following are the author’s articles on the recent moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act.

- “What is behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act? A historical look at what exactly is behind the latest swing back of the pendulum of Japan’s agricultural policy, which has been subject to the vagaries of politics,” October 11, 2022

- “‘Kaiaku’ no Ketsumatsu ga Sukeru Shokuryo Nogyo Noson Kihonho Minaoshi: Hogo Nosei heno Yurimodoshi Hakaru Nosei Toraianguru to ‘Osumitsuki’ no Tamedake no Shingikai [Moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act will likely result in making the act worse: An agricultural policy triangle that tries to make the agricultural policy more protection-oriented again, as well as the Council that only rubber-stamps everything that comes before it],” October 21, 2022

- “Lies and deceptions behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act: The truths that you should know so as not to be deceived,” November 2, 2022

- “Time to overhaul Japan’s post-war agricultural policy and administration: What should be the basic principles in revising the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act?,” December 1, 2022