Media Global Economy 2023.01.25

Time to overhaul Japan’s post-war agricultural policy and administration

What should be the basic principles in revising the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act?

The article was originally posted on RONZA on December 1st, 2022

I have written three articles on the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act (“the Basic Act”). They focus on three subjects among others. The first subject is what is behind the recent moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act. The second is which direction the Japanese government intends to orient the revision. Here, the Japanese government can be paraphrased as the agricultural policy triangle, which comprises the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA), the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), and the lawmakers of the governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who represent agricultural interests. The third subject is what the Japanese public should know about food and agriculture when they think about the Basic Act. This article considers what perspectives and basic principles are needed for the public to gain access to stable food supply.

The revising process is led by the agricultural policy triangle

Before that, let me summarize what I have discussed.

(1) International pressure to open the Japanese market to foreign agricultural products has waned now, and so have Japan’s agricultural circles’ eagerness and sense of urgency to implement agricultural structural reforms as called for by the current Basic Act. Instead, there have recently been calls to maintain small-scale, inefficient farming and the agricultural sector population. Maintaining both benefits the agricultural policy triangle, especially the JA.

(2) The agricultural policy triangle is trying to take advantage of the public’s growing interest in food security amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to increase the protection of domestic agriculture. But boosting the production of wheat and soybeans would repeat the past mistake.

(3) In Japan, scholars and researchers tend to snuggle up to the agricultural policy triangle in an effort to get ahead in the university hierarchy. This is contrary to what is expected of them. They are supposed to provide insights free from the interests of specific groups. At government councils, they are supposed to check any move that may undermine the benefits of agriculture, most notably its multifunctionality and the food security it provides.

(4) As most Japanese people have distanced themselves from agriculture and rural areas, the public generally believe false claims made by the agricultural circles, most notably the claim that farm households are poor. This misguided belief constitutes a major factor behind the implementation of policies that go against the benefit of the public as a whole.

(5) All these factors explain why the government adopts and implements policies that accommodate the vested interests of the JA and other components of the agricultural policy triangle – policies that are not for the public good or based on scientific approaches of economics.

The following are the author’s articles on the recent moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act.

“What is behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act? A historical look at what exactly is behind the latest swing back of the pendulum of Japan’s agricultural policy, which has been subject to the vagaries of politics,” October 11, 2022.

“‘Kaiaku’ no Ketsumatsu ga Sukeru Shokuryo Nogyo Noson Kihonho Minaoshi: Hogo Nosei heno Yurimodoshi Hakaru Nosei Toraianguru to ‘Osumitsuki’ no Tamedake no Shingikai [Moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act will likely result in making the act worse: An agricultural policy triangle that tries to make the agricultural policy more protection-oriented again, as well as the Council that only rubber-stamps everything that comes before it],” October 21, 2022

“Lies and deceptions behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act: The truths that you should know so as not to be deceived,” November 2, 2022

Unfortunately, the government will likely take no heed to the above observations and criticism and revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act in the direction intended by the agricultural policy triangle. I am convinced that the government’s policy on this issue has already been determined.

The Japanese public themselves should mull over what the agricultural policy should be like

The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries says he will listen to people from all walks of life. To this end, the government will take one year to discuss the issue at a subcommittee of the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies, which has been set up under the Basic Act. The council members seem to come from all walks of life in form, but they have been appointed by the MAFF, which is part of the agricultural policy triangle. The MAFF will not appoint researchers who point out problems with Japan’s agricultural policy, wholesalers who are almost out of business owing to declining rice production, or needy persons who cannot afford to buy rice. Moreover, the material the MAFF presents to the Council is designed to lead the discussions to certain conclusions. It could not possibly present reports that go against the wishes of the agricultural policy triangle. The Japanese public should independently consider what the Basic Act and the agricultural policy should be like.

The current agricultural policy violates the Basic Act

Japan’s agricultural policy and administration to date have hurt the stable supply of food at reasonable prices (food security) and the multiple functions performed by agriculture (multifunctionality) as provided for in the current Basic Act.

Multifunctionality and food security can be described as joint products associated with agricultural production or as economic externalities of agriculture. Only when paddy fields are used as paddy fields can agriculture exercise its multifunctionality as represented by flood control and water resource replenishment. Maintaining paddy fields leads to food security as well.

And yet, the government has been taking the rice production adjustment policy (the rice acreage reduction program), which grants subsidies to farmers who refrain from using paddy fields as paddy fields. This policy has undermined such benefits of agriculture’s multifunctionality as flood control and water resource replenishment. It has also undercut food security by encouraging the conversion of paddy fields for other purposes. Total paddy fields in Japan amounted to 3.5 million hectares in 1970, when the acreage reduction program was launched. Now, it stands at 2.4 million hectares, of which one million hectares or 40% are subject to the program.

In other words, two million hectares or 60% of the total paddy fields that existed at the beginning of the program are now lost or not used as paddy fields. In short, for more than half a century, Japan’s agricultural authorities themselves have been executing policies that go against both the goals stipulated in the Basic Act and the interests of the public as a whole.

Rice wholesalers have halved in number over the past four decades

As a matter of fact, no one in Japan’s agricultural circles framed a policy to achieve the purpose of multifunctionality or food security. By taking advantage of the fact that agriculture brings about the benefits of multifunctionality and food security, these circles have misled the public into believing that any policy will do as long as it concerns agriculture.

Agricultural economic researchers intently discuss the minute details of agricultural policies that benefit the environment. But they keep mum about the fact that the acreage reduction program significantly affects the environment. To date, they have argued about ways to improve the program so as to lessen the negative impact on agricultural actors. But they have never questioned the acreage reduction policy program itself for public good at large.

Not only farm households and the JA but also rice wholesalers are involved in the rice sector. As the amount of rice produced and distributed has more than halved over the past 50 years, many medium- and small-sized rice wholesalers have been forced to close down. The number of wholesalers decreased by half from 279 in 1982 to 142 in 2021. Yet, unlike farm households, they had no politicians who represented their interests. They fell victim to the rice policy of the agricultural policy triangle.

To date, Japan’s agricultural administration has been run for the benefit of the JA and other components of the agricultural policy triangle, an interest group. The MAFF is not a servant of the people. Japan’s agricultural administration run by the MAFF not only violates Article 1 of the Basic Act, which defines its purpose as “to stabilize and improve the lives of citizenry and achieve healthy growth of the national economy”; it also violates Article 15, paragraph (2) of the Constitution of Japan, which provides that “all public officials are servants of the whole community and not of any group thereof.”

The problem lies not with the Basic Act but with the agricultural policy and administration that run counter to the purpose of the Basic Act. The Japanese public must get back agricultural administration from the agricultural policy triangle and take it into their own hands.

The interests of the few are totally different from those of the nation

Kunio Yanagita (1875–1962), who joined the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce (MAC) after obtaining a Bachelor of Laws, made the following statement:

“Although it is obvious that what is called national interests and policy cannot exist detached from the people, the interests of the few or a certain class completely differ from those of the nation. This point deserves special attention in considering agricultural policy.” (See Teihon Yanagita Kunio Shu [Complete authoritative collection of Kunio Yanagita’s works], Vol. 28, pp. 195–196.)

As a former MAFF official who respects his achievements at the MAC, predecessor of the MAFF, I cannot bear to look at what the current ministry is doing now.

Basic principles in developing and implementing agricultural policies for the public

The government must secure and improve such benefits of agriculture as food security and multifunctionality for the benefit of the public as a whole, free from the perspective of a specific interest group. What basic principles, then, should the government follow in developing policies on food, agriculture, and rural areas?

The most important and fundamental principle is to ensure the stable and affordable supply of food to the public and consumers. It is essential to base any discussion on the issue on this principle. To date, Japan’s agricultural authorities have advocated the interests of farmers and farm households and, in so doing, worked to realize the interests of the agricultural policy triangle. Yet the interests of farmers and farm households are only secondary for a stable food supply for the public.

Suppose the Japanese public need 20 million tonnes of food as a minimum for their survival but have only one trillion yen to spare for food. If one trillion yen can buy five million tonnes of domestically-produced food or 25 million tonnes of imported food, there is no other choice but to buy imported food. This is because if the public stick to costly, domestically-produced food, they will die of hunger. (Even in this case, however, domestically-produced food will not be lost because a certain amount, say, one million tonnes, of such food is available at prices corresponding to those of imported food.)

Some may suspect that domestic agriculture could not be maintained in this way. But this is an issue that Japan’s agricultural sector should address by improving its international competitiveness. To date, the domestic agricultural sector has taken it for granted that it deserves protection. It has blamed the government for any decrease in the prices of farm products and demanded that it be protected from falling prices. Falling prices of food and farm produce are favorable for the public and consumers. An agricultural sector that fails to make efforts to cut costs and deliver on its responsibility in the face of falling prices does not deserve protection. This kind of logic is intrinsic to agricultural fundamentalism.

Nowadays, however, pseudo-agricultural fundamentalism is gaining traction. The JA leadership now often says that agriculture is the foundation of the state. The latest Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, which has been drawn up based in the Basic Plan, stresses the need for the public as a whole to share the awareness that agriculture is the foundation of the state. Such a statement is unusual in government documents.

“Agriculture that does not constitute the basis of the state is unworthy of thought”

This statement goes against the philosophy of Tadaatsu Ishiguro (1884–1960), a known agricultural fundamentalist and a leading figure responsible for agricultural policy in pre-war Japan. As Minister of Agriculture and Forestry in the Cabinet of Fumimaro Konoe, Ishiguro addressed some 15,000 farmers. He said:

“The belief that agriculture is the basis of the state does not mean that only benefits for agriculture should be sought. Our ideals, which are regarded by the public as being of what is called nohon-shugi (agricultural fundamentalism), are far from such a self-serving idea. We value agriculture simply because it is the basis of the state. Agriculture that does not constitute the basis of the state is unworthy of thought.” (See Otake, Keisuke. Ishiguro Tadaatsu no Nosei Shiso [The agricultural policy philosophy of Tadaatsu Ishiguro]. Rural Culture Association, 1984, pp. 247–248.)

It is not that farm households should be unquestionably protected. The protection of agriculture is none other than the compensation for farm households executing their mandate. This is what real agricultural fundamentalism is all about. As detailed below, Japan’s agricultural circles have continued to reduce rice production to keep rice prices high. Should imports be halted now, severe hunger would result. Japan’s agriculture today is far from the foundation of the state.

Farm households should not be treated as a vulnerable group

The underlying idea behind this principle is that advancing the interests of farmers and farm households and increasing their income should not constitute policy objectives. Farm households are no longer poor or vulnerable. Since 1965, farm household income has been higher than the income of salaried workers’ households. Poverty has long disappeared from farm households and rural areas. The average net income of households engaged in large livestock farming exceeds 40 million yen.

Increasing earnings and income is what each farm household and farmers should aim to do; it is not what the government should do. Could increasing the earnings of Toyota be a national policy objective simply because it is an important corporation for Japan? There is no reason to treat farmers and farm households differently from the general public. The government has been treating farmers and farm households, who are far from being vulnerable, as a vulnerable group. This has increased their psychological dependence on the government and undermined their spirit of self-reliance. Unfortunately, such tendency is also seen in households engaged in a large business farm. For farm households, it makes sense to pretend to be vulnerable in order to gain protection from the government.

Observations by Tanzan Ishibashi (1884–1973), the 55th prime minister of Japan, are still relevant to farmers today. Before WWII, Ishibashi was a journalist based in Toyo Keizai, Inc. and an advocate of a “Small Japan” policy. He said:

“Many people argue that Japanese agriculture cannot possibly stand on its own as an industry and thus is in need of protective tariffs. They argue that it needs low-interest loans. [...] The government, the Diet, the Imperial Agricultural Association, scholars, newspaper reporters, and practitioners all find every opportunity to stress that agriculture is in a sorry state. They all base their argument on the premise that agriculture does not pay as an industry. All leading intellectuals and institutions have convinced farmers that farmers cannot stand on their own feet, thus weakening their resolve. They have also convinced them that farming is not worth the effort, thus dashing their glimmer of hope. These are the root causes of the miserable state of Japan’s agriculture today.” (See Ishibashi Tanzan Zenshu [The complete works of Tanzan Ishibashi]. Vol. 5, p. 317.)

Agricultural administration that disregards the responsibility to supply food as called for in the current Basic Act

Article 2, paragraph (4) of the current Basic Act states:

“Supply of the minimum food necessary for citizens must be secured in such a manner that no serious hindrance will be caused to the stability of citizens’ lives or to the smooth operation of the national economy even where the domestic food supply and demand balance becomes or is likely to become extremely tight for a reasonable period of time owing to a contingent cause such as poor harvests or interrupted imports.”

Contrary to what the agricultural policy triangle argues for, the current Basic Act provides for a food crisis. In a crisis of import disruptions, how much food would Japan need?

In such a case, Japan would not be able to import wheat, beef, or cheese. The livestock sector, which depends on imported grains, would be devastated. The Japanese public would have no choice but to adopt a diet with minimum calories for survival, which corresponds to the diet in the aftermath of World War II, which primarily depended on rice and sweet potatoes.

The standard daily rice ration per adult back then was two go and three shaku (about 330 grams), which was once reduced to two go and one shaku (about 300 grams). To provide 125.5 million people (Japan’s population) with that ration (half that ration is assumed for children below the age of 15), Japan would need 16 million tonnes of brown rice. This represents the minimum food necessary for citizens as provided for in Article 2, paragraph (4) of the Basic Act. In short, agricultural authorities have been implementing policies that run counter to this provision.

The JA has been “killing” domestically-produced rice

To overcome the food shortage shortly after the war, farm households worked hard to boost rice production, which increased from nine million tonnes around 1945 to 14.45 million tonnes in 1967. Thereafter, however, the acreage reduction program has reduced rice production. The MAFF set the upper limit of rice production for this year at 6.75 million tonnes. The actual production amounted to 6.7 million tonnes. This represents less than half the figure for 1967.

The JA has recently been advertising the idea of domestic production for domestic consumption. Yet what the JA has long been doing is to “kill” domestically-produced rice. If an import disruption crisis occurred, the Japanese public would have access to only eight million tonnes of rice, including feed rice and the government’s emergency stocks of rice. This figure is about half the necessary amount. More than half of the Japanese public could not afford to buy rice and would eventually die of hunger.

This would be the tragic consequence of the nation-destroying policy of reducing rice production and acreage, a policy that has been promoted by the MAFF and the JA, both of which ostensibly call for food security and higher food self-sufficiency. This state of affairs has been brought about by agricultural policies that pursue the interests of farmers and farm households as well as their organization called the JA, rather than the interests of the public at large.

The agricultural policy triangle has been reducing rice production, citing the need for high rice prices to maintain rice production. That is ridiculous. Global rice production today is 3.5 times larger than the 1960 level. Rice production in Japan fell 40% during the same period. On top of that, Japan went out of its way to reduce the production of rice – the national staple food – with subsidies. What other country in the world would do such a thing?

What should be changed is the agricultural policy promoted by the agricultural policy triangle.

New principles that should be included

Nevertheless, the Basic Act, which was formulated more than two decades ago, needs to be revised. It should be revised to better cope with environmental challenges such as global warming and climate change. Japanese people erroneously believe that agriculture is friendly to the environment. But this belief is a great myth. Even before climate change came to the fore, it was widely known in the West that agriculture causes environmental stress.

“Conventional farming method” is a strange agricultural term. This term does not refer to the farming that does not use agrochemicals or chemical fertilizers, like the method widely used in pre-war Japan. It refers to the current farming method that uses large amounts of agrochemicals and chemical fertilizers. Organic farming, agrochemical-free farming, and other farming methods that take much time and effort are not suitable for part-time farm households, which can spare time to farm only on weekends. In pre-war Japan, chemical fertilizers were widely used but agrochemicals were not. The conventional farming method is a post-war method.

Paddy fields nurtured diverse living things. They provided habitats for diverse small living things such as frogs, Dojo loaches, mud snails, and dragonfly nymphs. They also provided feeding grounds for white storks, Japanese crested ibises, and Japanese cranes. There were some types of living things that lived in paddy fields. A good example was tadpole shrimps, which lived as eggs in winter, during which paddy fields were dry. As agrochemicals came to be widely used after WWII, Japanese diving beetles, giant water bugs, and mud snails disappeared. White storks and Japanese crested ibises became almost extinct. Around 1970, as I was walking along a canal in a countryside, I saw large numbers of dead carps and catfish some 60 centimeters long floating in the stream with their white bellies up. They had fallen victim to the massive use of agrochemicals. That sight is still vivid in my memory. The Autumn darter, also known as the red dragonfly, lays eggs in paddy fields in autumn. The eggs hatch in spring and the dragonfly nymphs live there until they metamorphose into red dragonflies. The number of Autumn darters has plummeted owing to the new type of agrochemicals that began to be widely applied in the 1990s. It may be that red dragonflies will disappear in Japan.

Agrochemicals and nitrogen fertilizers are used in large quantities in farming in Japan

If business farm households that practice eco-friendly farming accounted for almost all of rice production, the impact on ecosystems would be minimum. The reality, however, is that part-time farm households make up some 70% as they have stayed in the business owing to the high rice price policy. Paddy fields represent more than half the total farmland in Japan. They are largely managed by part-time farm households that apply large amounts of agrochemicals and chemical fertilizers, not by business farm households.

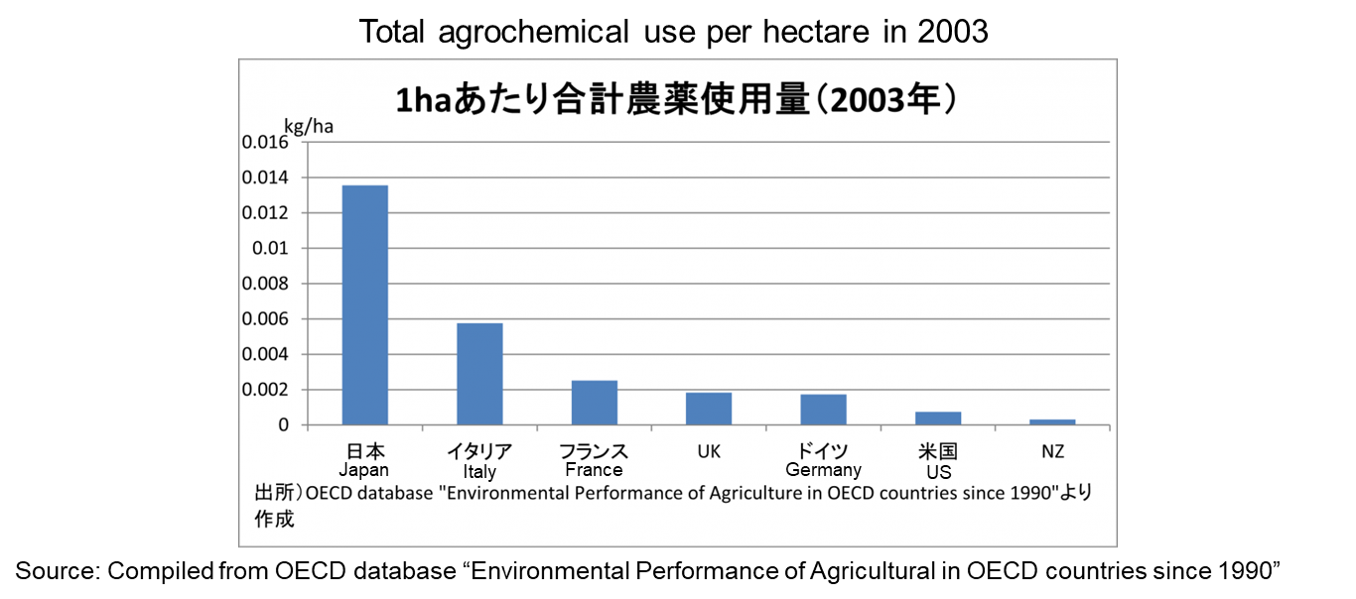

The total agrochemical use per hectare in Japan is 18 times larger than that in the United States. One factor for the larger use of agrochemicals is that weeds tend to grow more luxuriantly in Japan as it enjoys lusher vegetation. Another major factor is a large number of part-time farm households.

Groundwater pollution by nitrogen is a major issue in the US and Europe. In this context, it is worth noting paddy fields’ slow increases in nitrate nitrogen concentrations in groundwater that are attributable to farming. Paddy fields break down ammonia in nitrogen fertilizers and release nitrogen gas (nitrous oxide, as discussed later) into the atmosphere. Studies show that the gas thus released from paddy fields contributes less to global warming than methane.

Nevertheless, the input of nitrogen fertilizers per hectare in Japan is more than twice the world average. More than 40 years of rice acreage reduction have substantially dwindled the capacity of paddy fields to decompose nitrogen compounds. The combination of nitrogen fertilizer input and acreage reduction may pose health hazards through groundwater pollution in the future.

Why has the practice of double-cropping rice and wheat in paddy fields disappeared?

Studies suggest that the double-cropping of rice and wheat in paddy fields produces almost the same unit amount of oxygen from photosynthesis as tropical rain forests do. The combination of the primary cropping of rice and the secondary cropping of wheat in paddy fields, which is also good for the environment, has now been replaced by the mixed husbandry of the single cropping of rice and salaried work.

Why has the practice of growing wheat as a secondary crop disappeared? In the past, farmers harvested wheat in June before planting rice. This practice was best expressed by the term bakushu (literally “wheat autumn”), which refers to the early summer period from late May to early June, during which wheat ripens. Over time, part-time farm households whose main income came from salaried work increased in number. They were able to plant rice only during the consecutive holidays in May. So they had no time to harvest wheat. This was how double-cropping almost ceased to exist. The high rice price policy prompted farm households to choose rice over wheat. Scenes of wheat ripening during bakushu have become a thing of the past.

Regulations regarding agrochemical residues are in place to ensure the safety of farm products. Yet agricultural policymakers have paid little attention to the fact that agrochemicals and chemical fertilizers adversely affect the environment.

Methane emissions from paddy fields can be prevented

In regard to climate change, the agricultural sector accounts for some 20% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Of these GHGs, methane comes chiefly from paddy fields and cattle belching. Methane is 25 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than CO₂ (carbon dioxide). Reducing methane emissions makes a big difference.

Paddy field soils are home to microorganisms that generate methane (methanogen) in oxygen-deficit (anaerobic) conditions. After farmers draw water into paddy fields to grow rice, oxygen concentrations in the soil fall, prompting the generation of methane. Yet farmers may drain paddy fields (in the practice known as mid-summer drainage) and often supply irrigation water containing oxygen. This prevents methane generation in a reduced state. US studies have demonstrated that the use of seaweed as a feed additive is effective in reducing cattle belching. This method has already been implemented in the United States.

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen monoxide), a little known GHG, is 300 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. It is generated from nitrogen fertilizers.

Yet harvesting farm products can remove nitrogen from the farmland. In the US, the idea of nitrogen balancing (N-balancing), which is aimed at removing as much as possible the nitrogen content of fertilizers that have been applied to farmland by harvesting crops, is being seriously discussed.

Promoting livestock farming is an ill-conceived idea as it is especially eco-unfriendly

Livestock farming has an especially negative impact on the environment among other agricultural subsectors. Japanese livestock products are so dependent on imported grains such as corns that it could be described as being processed from such grains. Such livestock farming cannot fulfill its duty to provide the public with food because it would be devastated in a food crisis in which the import of feeds is disrupted. Livestock farming entails much environmental stress. Japan’s livestock sector imports large amounts of feed. This accumulates nitrogen in large quantities across Japan because animal waste is not plowed back into cultivating grains. For the good of the environment, it is better to import beef and pork rather than grains for feed. Livestock farming in Japan entails more health hazards as well. It commonly feeds cattle with grains, and grain-fed beef contains larger amounts of omega-6 fatty acids than pasture-fed beef. Omega-6 fatty acids, which are also contained in pork and butter, cause myocardial and cerebral infarction. On top of that, some livestock farmers in Japan raise animals in such poor conditions that animal welfare experts from the West would faint if they saw such a sight.

Livestock farming has all these negative economic externalities. It is an ill-conceived idea to protect it with high tariffs or promote it with subsidies. From the perspective of the Polluter Pay Principle (PPP) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the government should curtail livestock production by imposing taxes. Animal waste and cattle belching generate methane, a GHG. Amid mounting pressure to address global warming, policymakers around the world are contemplating reducing livestock farming by introducing plant-based meat substitutes and cultured meat. Meanwhile, livestock authorities in Japan offer a wide range of subsidy programs in addition to price support.

A science-based agricultural policy rooted in economics is needed

“Evidence-based policy making” (EBPM) seems to be the buzzword in Japan’s government center of Kasumigaseki. EBPM is endorsed in the Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas, which was formulated in 2020 by the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies. The Basic Plan states: “The government will identify policy objectives and promote evidence-based policy making in light of such policy objectives. […] The government will make a scientific and objective analysis of policies to assess their relevance and effectiveness.”

In EBPM, policy objectives are identified first and then policies are developed to effectively achieve such objectives. The process of making agricultural policies in Japan follows this order in reverse. First, policies are developed by the agricultural policy triangle through political maneuvering. Then their objectives and rationales are concocted to justify them. The Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies just rubber-stamps everything that comes before it.

The situation is similar for agricultural public works projects as well. To win project approval, project planners do everything they can to overestimate benefits and underestimate costs. Because only minimum costs are calculated at the time of project approval, necessary expenses will snowball after the project launch. For example, if a dam project is launched without adequate subsurface exploration, expenses for ensuring the safety of the dam will increase. Once a project is initiated, the government will never abort it. Even if it is found to have an unequivocally negative impact on the national economy, the government will continue with the project, arguing that aborting it hallway would waste all the tax money that had been put into it.

A good example is the Isahaya Bay reclamation project from 1986 to 2008. The project spent a total of 253 billion yen in tax money to develop a farmland area of 870 hectares. In other words, one hectare of farmland costed 300 million yen. The figure dwarfs the average sale price of one hectare of farmland in Japan: 6.89 million yen for paddy fields and 4.24 million yen for upland fields (according to a 2020 survey by the Japan Real Estate Institute). Farmland in Japan is known to be more expensive than that in western countries. The public paid an exorbitant price for the newly developed farmland. To secure farmland, it is far less costly to strictly control farmland conversion or restore abandoned farmland.

The rice acreage reduction program cannot be justified by any means

As discussed earlier, the rice acreage reduction program has reduced the total area of farmland, which is essential for food security. It has also undermined the multifunctionality of agriculture. Flood control and water resource replenishment are some of the economic externalities of rice production in paddy fields. How can the program be justified in terms of food security or multifunctionality? This is the question I want to ask the members of the agricultural policy triangle, especially MAFF officials, as well as economists who sit on the Council of Food, Agriculture and Rural Area Policies.

Suppose these people brazen it out and admit that the program is designed to keep rice prices high by reducing rice production with subsidies. Then I must say that it is a superb program that has virtually achieved its objectives. In fact, it has achieved almost in full the appropriate rice production (an effective upper limit) and the production/acreage quotas, both of which are set by the MAFF. In that sense, the acreage reduction program could be described as a policy based on EBPM. However, cost-benefit analysis, an instrument used by economists, shows that the program is the worst policy imaginable because it increases the burden on consumers (by raising rice prices) with taxpayers’ money (acreage reduction subsidies). What is needed is cost-benefit analysis, not EBPM.

The following are the author’s articles on the recent moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act.

“What is behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act? A historical look at what exactly is behind the latest swing back of the pendulum of Japan’s agricultural policy, which has been subject to the vagaries of politics,” October 11, 2022.

“‘Kaiaku’ no Ketsumatsu ga Sukeru Shokuryo Nogyo Noson Kihonho Minaoshi: Hogo Nosei heno Yurimodoshi Hakaru Nosei Toraianguru to ‘Osumitsuki’ no Tamedake no Shingikai [Moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act will likely result in making the act worse: An agricultural policy triangle that tries to make the agricultural policy more protection-oriented again, as well as the Council that only rubber-stamps everything that comes before it],” October 21, 2022

“Lies and deceptions behind the moves to revise the Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas Basic Act: The truths that you should know so as not to be deceived,” November 2, 2022