Column Finance and the Social Security System 2021.06.17

【Aging, safety net and fiscal crisis in Japan】No.309:Long-term care service fees have increased by an average of 0.7% due to the COVID-19 pandemic

In this column series, Yukihiro Matsuyama, Research Director at CIGS introduces the latest information about aging, safety net and fiscal crisis in Japan with data of international comparison

In 2000, Japan established a long-term public care insurance system. Reflecting the fact that population aging is accelerating, the total long-term care expenses increased from JPY 3,627 billion (US $ 33 billion) in 2000 to JPY 10,432 billion (US $ 95 billion) in 2018. The required financial resources in 2018 were JPY 9,377 billion (US $ 85 billion), which was the total expense of JPY 10,432 billion minus the JPY 1,055 billion paid by long-term care service users (beneficiaries). As explained in Column No.143, 50% of this financial resource burden is taken on by the government (tax), 27% comes from workers aged 40–64 years (premium), and 23% comes from those aged 65 years and older (premium). The insurance premiums and fees for long-term care providers are revised every three years to reflect the financial condition of the system.

However, the Ministry of Finance argued in 2020 that there was no need to raise long-term care service fees because the average operation margin in long-term care service providers was as high as 5.2% in 2019. This does not accurately reflect the fact that amid the COVID-19 pandemic, long-term care service providers have been suffering from factors that deteriorate profits. These include the cost burden of infection prevention measures, the decrease in revenue due to the forced suspension of home-visit nursing care services, and the wage increase to secure human resources. Therefore, the government decided to raise long-term care service fees by an average of 0.7% in the three years from 2021 to 2013.

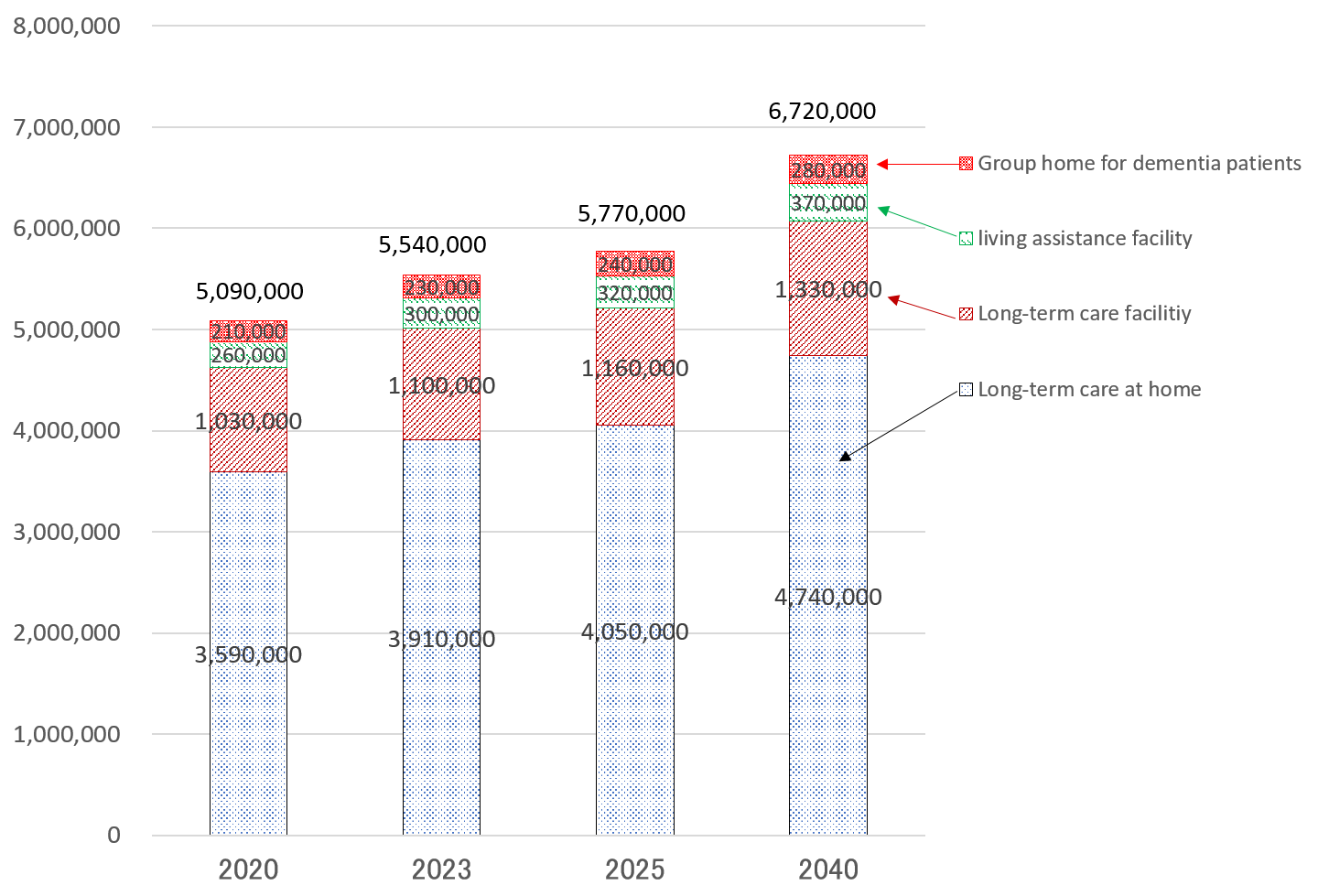

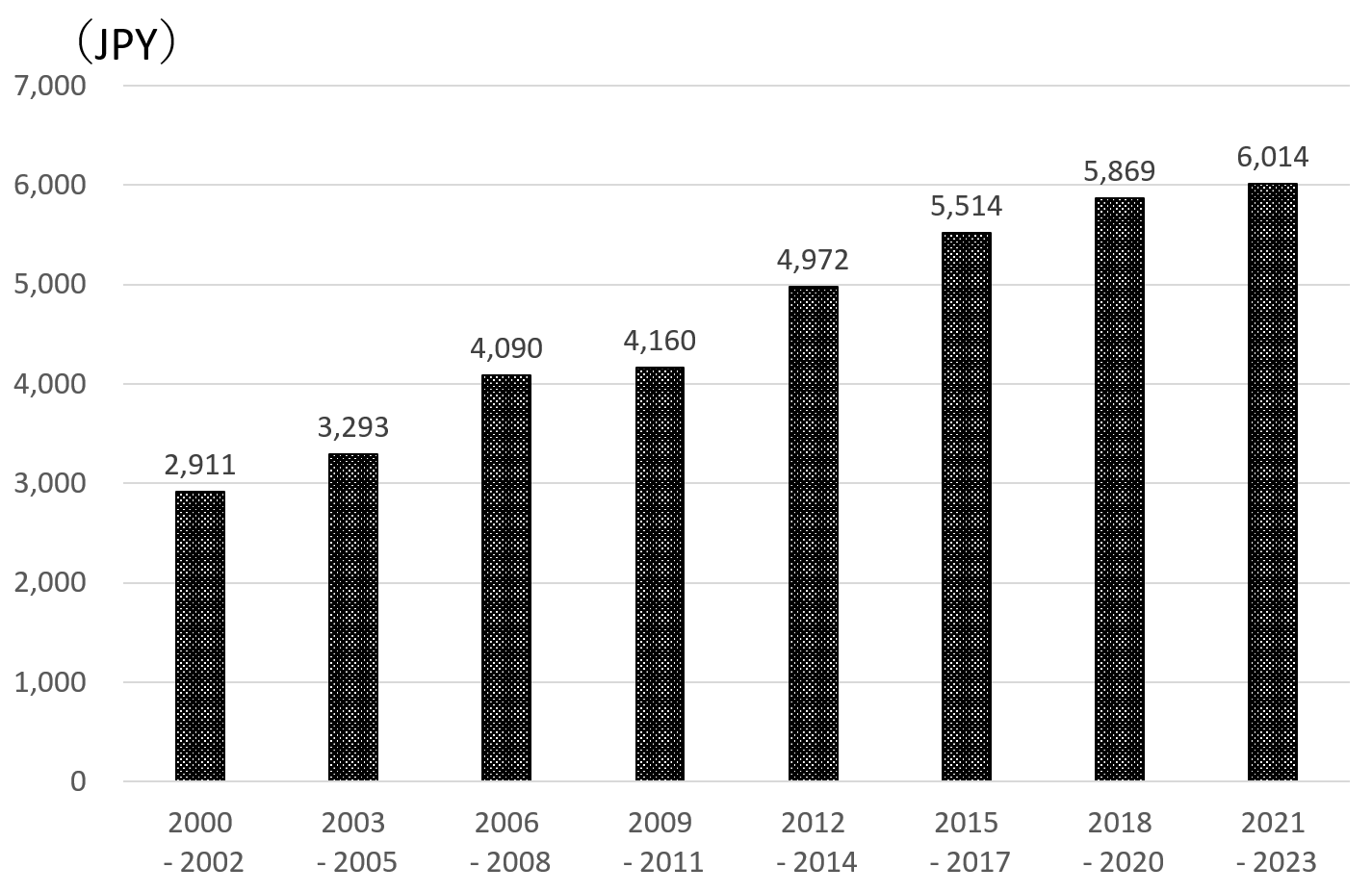

The government estimates that the number of long-term care insurance beneficiaries will increase from 5,090,000 in 2020 to 6,720,000 in 2040. Therefore, the financial resources required to maintain the system will continue to grow, even if long-term care service fees do not increase. This means that the premiums borne by the elderly, who have a significant influence on politics, will rise. The national average of long-term care insurance monthly premiums borne by the elderly has risen from JPY 2,911 (US $ 26) in 2000–2022 to JPY 6,014 (USD 55) in 2021–2023 (Figure 2). The premium increase rate of JPY 6,014 in 2021–2023 compared to JPY 5,869 (US $ 53) in 2018–2020 is 2.5%, which is larger than the increase rate of 0.7% in long-term care service fees. This reflects an increase in the number of long-term care insurance beneficiaries.

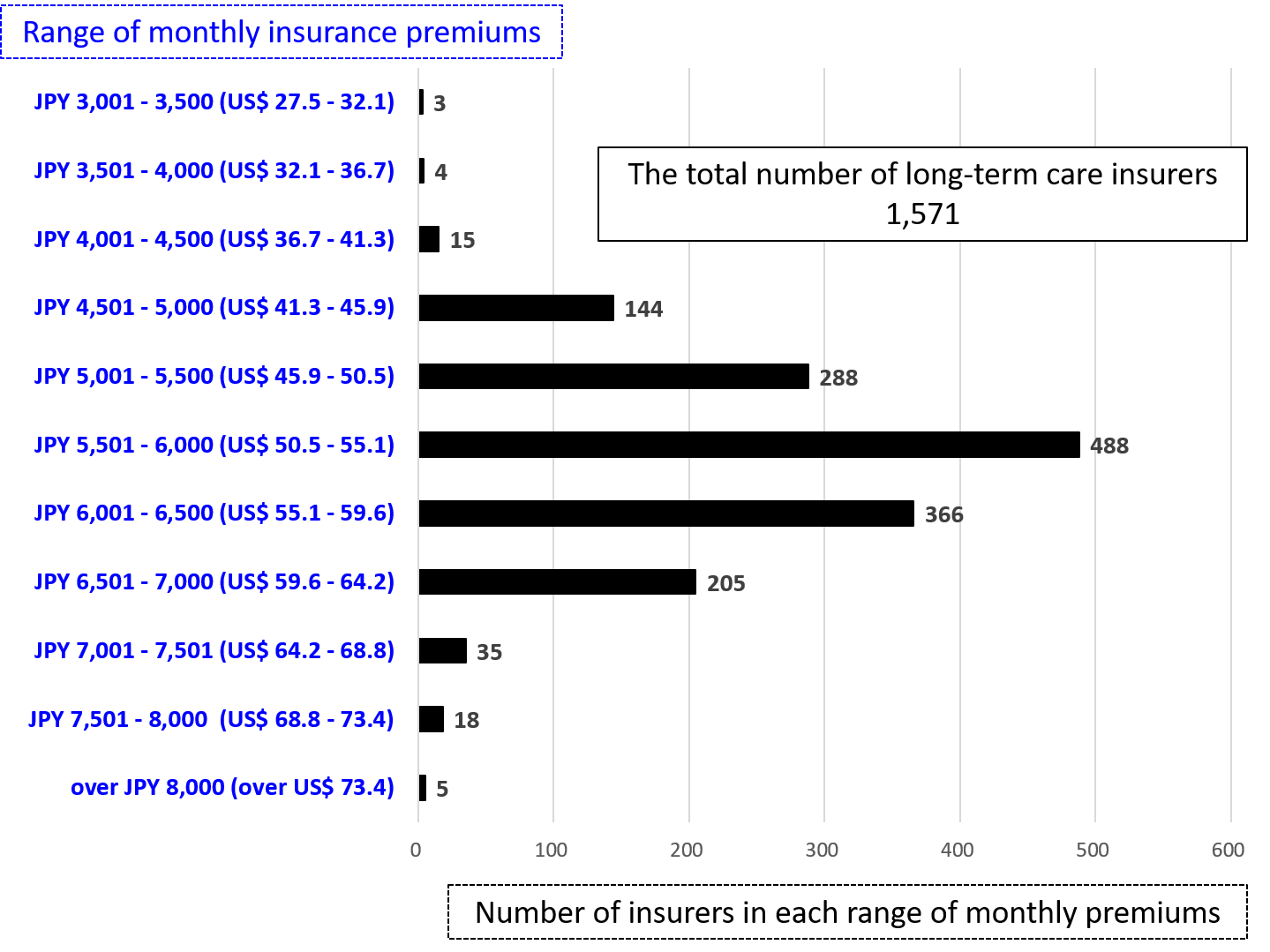

As the insurers in the long-term care insurance system are municipalities, the number of insurers is 1,571 (Figure 3). Premiums borne by the elderly are highly dependent on the percentage of the elderly in the area covered by each insurer, as well as the rate of use of long-term care services. While the average premium for 2021–2023 is JPY 6,014, the lowest is JPY 3,300 (US $ 30), and the highest is JPY 9,800 (US $ 89), which is approximately three times as much.

Figure 1. The number of long-term care insurance beneficiaries

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

Figure 2. National average of long-term care insurance premiums borne by the elderly

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

Figure 3. Distribution of monthly premiums in 1,571 long-term care insurers

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare