Media Global Economy 2020.04.10

For Whom Are the Food/Agricultural Policies? : Officials in the "Agriculture Village" Disregard Stable Supply

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) says that by supporting the food bank, it will supply the economically disadvantaged with food to be discarded. But it is its very agricultural policy that prevents the poor from buying foodstuffs by keeping their prices high to protect agriculture. The goal of such agricultural policy is to double income in agriculture and agricultural villages. This is because the votes of farmers are becoming increasingly important in elections. But farmers are far from being poor and are unusually large-income earners. Is a policy of supporting those who drive a Porsche and eat foie gras with taxpayers' money rather than holding out a helping hand to those who suck in cup noodles in an apartment appropriate?

MAFF supports the food bank

The food bank is an initiative to provide welfare facilities and the needy with foodstuffs excluded from the distribution channel because of problems such as packaging and the passing of the best-before date though they are still good enough. The Ministry has announced that in order to support the food bank, it will collect information on such foodstuffs from food manufacturers and supermarkets and establish a system to provide them to activist organizations and welfare facilities by the end of fiscal 2020. Some local newspapers published this announcement as a top news item on the first page. This is proof that there are many needy persons.

While some people suffer from famine in developing countries, obesity due to plentiful food is becoming a problem in advanced countries. The loss of food discarded without being eaten is a problem that is shared by both developing and advanced countries. In developing countries, however, the food loss problem is that even if agricultural products are harvested, or even if aid supplies from advanced countries arrive in ports, food does not reach those who need it for reasons such as underdeveloped roads and other logistic infrastructures. By contrast, advanced countries' problem involves rich consumers being oversupplied with food and ending up discarding it. In Japan, food loss totaled 6.43 million tons in fiscal 2004, and this was equivalent to about 90% of rice produced for a staple diet.

But even in Japan, there are people who cannot obtain food due to poverty and a lack of welfare facility budgets. The food bank is intended to alleviate the problem of food shortage amidst the oversupply or abundance of food--which arises from income disparities--by providing those people with foodstuffs that are going to be discarded. Support for the food bank looks like a favorable policy, but how do you evaluate it if MAFF itself is bringing about food shortages? If it is trying to solve the problem it has caused, it is not praiseworthy.

Two factors are involved if one cannot afford to pay for food. One is low income due to unemployment and atypical employment. The other is the inability to buy foodstuffs due to high prices. Even if one is poor, one does not find it difficult to make a living if the prices of foodstuffs are low.

Politicians, too, are not indifferent to this problem. Consumption tax is regressive in that the lower the income, the heavier the burden of paying the tax is. The government expressed deep concern that if the prices of foodstuffs rose as the consumption tax rate was raised from 8% to 10%, they would fall more heavily on low-income earners, who spent a high percentage of income on foodstuffs; in view of this, it applied a reduced tax rate to foodstuffs. But how seriously do politicians think about the fact that low-income earners cannot afford to buy foodstuffs?

Agricultural administration runs counter to the reduced tax rate

The "Agriculture Village," which consists of Agricultural Cooperatives, Diet members who lobby for the interests of farmers, and MAFF, argued that if Japan signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, its agriculture would be devastated, and Agricultural Cooperatives collected over eleven million signatures against TPP. After Japan joined TPP negotiations, the Liberal Democratic Party and the Diet committee insisted that rice, wheat, beef, pork, dairy products, sugar, etc. should be excluded as exceptions from the list of items on which tariffs should be lifted and resolved that if this was not possible, Japan should be ready to withdraw from the TPP negotiations.

Politicians described TPP negotiations as a battle to which Japan committed its national interests. What they called "national interests" was to protect tariffs on agricultural products. Protected by such tariffs are domestically produced, high-priced agricultural products (or foodstuffs). This protects farmers, and consumers pay for expensive foodstuffs.

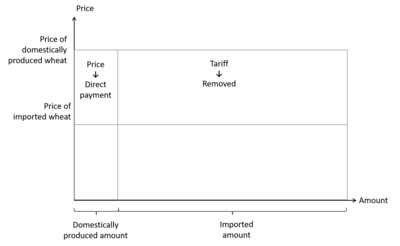

For example, in order to protect the high prices of domestically produced wheat, which accounts for only 14% of the total amount of wheat consumed, a tariff (to be precise, a surcharge collected by MAFF) is imposed on foreign-produced wheat, which represents 86%, and this forces consumers to buy high-priced bread and udon. If MAFF stops consumers from paying the difference between the domestic and international prices of agricultural products and grants subsidies directly to farmers from the public purse, one major benefit would be to render it unnecessary for consumers to make extra payments for such products. This would enable MAFF to reduce extra payments by Japanese consumers while protecting farmers in the same way as before (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Regressive Agricultural Administration

(Source) This figure has been created by the author.

Among foods and beverages, MAFF's policy for rice, a staple diet, is far more problematic. Under healthcare and other regular policies, consumers can be provided with goods and services at low prices if they pay their share as taxpayers. But MAFF annually grants subsidies to farmers using the ¥400 billion paid by taxpayers and lets them reduce rice production (practically acreage reduction), thus keeping rice prices much higher than the ones that would be realized by markets and forcing consumers to pay more for rice. This high price of rice is also made possible by the imposition of tariffs. Incidentally, the Abe administration announced its policy to stop acreage reduction, but this is fake news.

Since the liberalization of beef in 1990, MAFF has spent a huge amount of state financial funds, which reached ¥3 trillion, on livestock industry, but the prices of livestock products such as meat and dairy products bought by consumers have conversely risen. Despite the tariffs reduced through TPP, the price of beef remains at historically high levels. The price of a domestically produced calf and beef has nearly doubled during the past two decades. The price of raw milk sold by dairy farmers continued to rise from ¥79.2 per kilogram in fiscal 2007 to ¥103.4 in fiscal 2018. If the price of raw milk rises, that of milk and dairy products also goes up. These price increases are a different world from the deflationary trend in the Japanese economy. The international competitive power must be enhanced by lowering prices as tariffs are reduced, but the result is completely the opposite of what is expected.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that Japanese consumers pay approximately ¥4 trillion more by buying products whose prices are higher than international ones. This is almost the same amount as the one that the government requires consumers to pay by raising the consumption tax rate last October. If the regressiveness of agricultural policy is resolved, consumers would not need to pay more even if the consumption tax rate is raised.

Even by international standards, agricultural administration is unusual

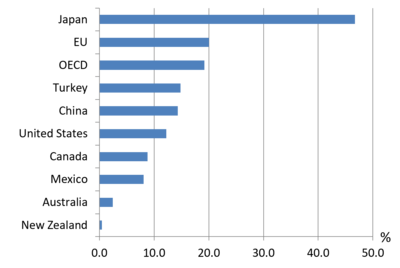

Let us compare agricultural policies in various countries. Developed by OECD, the agricultural protection indicator known as "producer support estimate (PSE)" consists of two parts: payments by taxpayers to maintain the income of farmers through state financial funds, and payments by consumers as obtained by multiplying the difference between domestic and international prices (difference between internal and external prices) by production volumes (amount of income consumers transfer to farmers by paying for high domestic prices rather than low international ones).

In 2018, while the percentage of PSE, or agricultural protection, to the amount received by farmers was 12.2% for the United States, 20.0% for EU, and 19.2% for the average of OECD member countries, that for Japan was extraordinarily high, at 46.7% (Figure 2). This means that government protection represents half of the amount received by farmers. In addition, a comparison with 1999, when the level of agricultural protection was high, indicates that while the percentage for the U.S. and that for EU each fell to nearly half from 25.5% and 38.5%, respectively, that for Japan decreased slightly by about 20% from 59.9%.

Figure 2 International Comparison of PSE (2018)

(Source)OECD "Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2019" This figure uses "PSE as a share of GFR(%) in Composition of Producer Support Estimate

This is not the only problem. In Japan, agricultural policy is carried out by putting the burden of paying high prices mainly on consumers.

The EU, which formerly protected agriculture through high prices as Japan did, has shifted to the policy of protecting farmers by paying directly to them through state financial funds while supplying consumers with low-priced agricultural products. In 1993, despite political resistance, the EU forced through reforms. The U.S. shifted its agricultural policy in the 1960s. Agriculture can be protected through direct payments. Moreover, if rice acreage reduction is stopped, state financial funds would not need to be spent on acreage reduction, and in addition, prices would be reduced, prompting high-cost, part-time farmers to withdraw and agricultural land to concentrate on full-time farmers. If full-time farmers expand their scale of agriculture, lowering costs and prices further, agriculture would develop, as the burden on consumers is reduced and exports grow.

Figure 3 Percentage of Price Support to Total PSE (Agricultural Protection)

(Source)OECD "Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2019"

Attempting to intervene in the market to protect farmers by keeping prices high causes oversupply, a problem that rice experienced in the 1970s. This is why the world's agricultural economists affiliated with international organizations such as OECD recommend direct payments, which distort markets less. If the problem is oversupply due to high rice prices, the main point of economic policy should be to lower the prices which cause the problem, but MAFF has simply taken the makeshift measure of resolving the oversupply which resulted from high prices---in other words, acreage reduction.

In terms of sales of agricultural equipment and materials, Agricultural Cooperatives boast of their overwhelming share, at 80% for fertilizer and 60% for agricultural chemicals and agricultural machinery and implements. Major provisions of the Anti-Monopoly Act are exempted from application because they are cooperative associations, however. They are also free to form cartels. The prices of major agricultural equipment and materials such as fertilizer, agricultural chemicals, agricultural machinery and implements, and feed are twice as high as in the U.S. though they use the same raw materials. One large farmer imports fertilizer from South Korea. He says that even if he has to pay for transport, South Korean fertilizer is 30% cheaper than the one he buys from an Agricultural Cooperative. If seen from causal relations in economics, farmers can afford to pay the high prices of agricultural equipment and materials because the prices of agricultural products are high. Agricultural Cooperatives can earn high sales commissions twice through the high prices of agricultural equipment and materials and those of agricultural products. In order to keep the prices of agricultural products higher than their international prices, tariffs are needed. Officials in the Agriculture Village argue that they are uneasy because protecting farmers through state financial funds requires budget deliberations at Diet sessions each year but that tariff-based protection can be continued constantly. But TPP has reduced the tariffs. Budgets, which can be nailed down through Diet deliberations alone, are politically easier than tariffs, which are determined through negotiations with foreign countries. Respectable policy would not need to fear Diet deliberations.

As shown by the example of wheat, even if the tariff on wheat is removed, and wheat prices fall, farmers would not be worried if they receive payments from state financial funds. But if wheat prices fall, revenue from sales commissions decreases, damaging the management of Agricultural Cooperatives. That is not the only damage. By allowing high-cost and small-scale part-time farmers to stay in the industry through high rice prices, Agricultural Cooperatives have not only been able to maintain their political power but also developed into Japan's second largest mega-bank as the extraordinary amount of earned income of part-time farmers off farms was deposited in Agricultural Cooperative accounts. Falling prices shake the foundation of Agricultural Cooperatives.

Agricultural policies in Japan is characterized by its high degree of agricultural protection, and in addition, over 80% of such protection is supported by payments by consumers. None of the politicians considers this as problematic, though they made such a big uproar about the regressiveness of consumption tax. For politicians who represent the interests of the Agriculture Village, it is exactly what they call "national interests" to maintain the current agricultural policies, an incarnation of regressiveness, which boosts the prices of foodstuffs by imposing tariffs.

In particular, rice forces double payments: high payments by taxpayers and high payments by consumers. Even if acreage reduction is stopped to lower rice prices, payments by consumers could be reduced and at the same time, those by taxpayers could be reduced if directs payments are limited to full-time farmers who make a living by agriculture.

Farmers are large-income earners

The objective of agricultural policies, which forces payments on low-income earners as well, is to increase the income of farmers. The ten-year strategy to double income in agriculture and agricultural villages, which was put together by the Liberal Democratic Party in 2013, aims at realizing a vision of doubling the income of supporters of rural communities, and following the strategy, at a Cabinet meeting, the government also decided to strive to double income in agriculture and agricultural villages. This became the policy goal of not only MAFF, but also the entire government.

The policy goal is nothing but the Abe administration's election tactics. Although the farming population is diminishing, organized farmers hold a casting vote under the single-seat electoral system and in single-seat districts for the House of Councillors. The reason is that if two candidates are contending fifty-fifty and at least 2% of organized votes go to one of the two, the results is 48:52 with the other allowing one to gain a 4% lead.

But are farmers so poor that the policy goal must be to double their income even at the sacrifice of low-income earners? In 1961, the Agricultural Basic Act was established to resolve the widening income disparities between agriculture and industry. But since 1965, due to the raising of rice prices and the progress of part-time farming, the income of farmers has continued to exceed that of workers. Today, there is no poverty in rural communities.

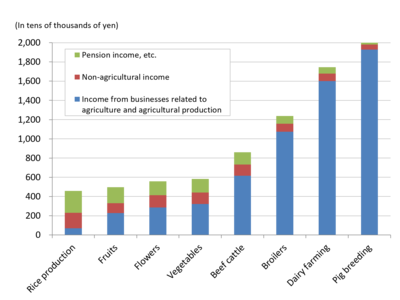

On the contrary, farmers are becoming high income earners. As indicated in Figure 4 (2017), even rice farmers who earned the lowest income (¥4.59 million or $42 thousand) exceeded the average annual income in the private sector of ¥4.32 million or $39 thousand. In the livestock farming industry, which annually receives a government subsidy of ¥300 billion in return for the lowering of tariffs based on TPP, Japan-U.S. trade agreements, and so forth, the annual income was ¥8.59 million or $78 thousand for beef cattle raisers, ¥17.43 million or $158 thousand for dairy farmers, and ¥20.45 million or $186 thousand for pig breeders. The income of large dairy farmers who raised 100 cattle or more was ¥49.76 million or $452 thousand, and that of those who bred 2,000 pigs or more was ¥66.76 million or $607 thousand (In the figure, non-agricultural income refers mainly to the income of salaried workers. The figure shows that rice is produced mostly by part-time farmers, whose main income comes from working as a salaried worker, and aged pensioners).

Figure 4 Income of Farmers by Farming Type

(Source) This figure has been created by the author using the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries' statistical survey of agricultural business (2017).

All sorts of measures are taken for these wealthy livestock farmers. If the prices of products they produce fall, the difference is compensated for. Large subsidies are granted when they build barns and introduce new livestock, machinery, and facilities. If they fail in business and incur debts, funds are offered for long-term, low-interest refinancing. Fiscal discipline has continued to slacken since the formation of the Abe administration.

Before World War II, farmers were poor, but workers were also poor. The Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce with which Kunio Yanagida stood, stayed on the opposite side of the land-owner class--who strove to gain profits by raising rice prices--in favor of Japanese consumers.

Prewar support for agriculture was intended to supply consumers with food at low cost in a stable manner by lowering costs and prices. Otherwise, it would be unreasonable to allow farmers, through public work program mainly paid by taxpayers, to improve the productivity of their own agricultural land by paying only around 15% of the improvement cost. Unlike bridges, roads, and other public utilities, their land is personal property. Agricultural administrators disregard their original mission and aim only at serving interest groups.