Media Global Economy 2018.07.23

The false claim that rising global populations will give rise to food crises - Closing in on the reality behind the fake news cooked up by agricultural experts from around the world

Rumors of global food crises are being spread by agricultural experts

There is a claim that is routinely made at the international conferences on agriculture and food held in countries all over the world. The claim goes something like this:

By the year 2050, the global population will increase by roughly 30% from its current level of 7.4 billion people to 9.6 billion people. In addition, per capita GDP will also rise due to economic development, and urbanization will advance. This in turn will lead to rising demand for animal products such as meat and dairy products produced by using grain as animal feed. This will cause substantial increases in the demand for grain. When viewed on the whole, the amount of food produced globally will have to rise by around 60%.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has propagated views to this effect, with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) of Japan publicizing similar outlooks as well. This is not limited to Japan, as experts from around the world express similar sentiments. I myself even bought into this line of thinking at one point.

At a conference held in the Netherlands this year, I tried posing a simple question to a university professor who raised an opinion to this effect.

"In your presentation, you stated that the global population will rise by 2.2 billion people over the next 35 years from 7.4 billion people to 9.6 billion people, but over the past 35 years the population rose at a faster pace than this, increasing by 3 billion people. We were able to accommodate this increase in the past, so why will we not be able to do so in the future? Moreover, it's not like there's going to be a sudden population explosion in 2050. If a food crisis were to occur due to the gradual rise in the population, grain prices should also continue to gradually and incrementally rise starting from now. Yet real prices for grain have fallen consistently over the past a century and a half. How do you explain this?"

He was unable to provide an answer, as there is no way to respond to this. Because this is nothing more than fake news that has been cooked up by the FAO, MAFF, and other agricultural officials and experts from around the world.

Food crises and price surges occur in a short-term manner

What happens when a food crisis occurs?

Two major food crises have occurred in Japan: the 1918 rice riots and the postwar food shortages. One thing they both had in common was a surge in the price of rice and other foodstuffs. Supply was unable to meet demand, and so prices rose. These events came about due to temporary and unpredictable reasons such as sudden surges in exports and significant reductions in production.

The surges in the price of grain that occurred in 1973 and 2008 could be mentioned as food crises that have occurred globally. These also came about due to temporary reasons, such as the sudden decline in global grain production, the purchases of vast quantities of grain by the Soviet Union, and the increased production of ethanol from corn on account of an abrupt policy change in the United States.

Despite the perpetually low price of grains and foodstuffs, these food crises came about due to unforeseen reasons such as bad weather that toppled the supply-demand balance, leading to price surges. These are referred to as "price pikes" (a pike is akin to a lance or javelin), because they are pointed like a pike.

Agricultural experts are clamoring about "chronic" food crises

As opposed to these, the food crises that are claimed will occur up through 2050 would involve ongoing price increases due to structural reasons such as supply being chronically unable to keep pace with rising demand. Whereas the food crises to date have all been temporary and transient in nature, these would be chronic in nature.

When imports of rice fell in the Philippines in 2008, many people had to line up in order to receive rations. The claim is that a similar state of affairs would persist every year.

In such cases, the prices of grains and foodstuffs would not be pike-shaped where they spike on just a temporary basis, but would increase in a chronic manner. If this theory is correct, then the prices of grains and foodstuffs should continue rising starting from now towards a high level in 2050. This is because both populations and incomes will gradually continue to increase, rather than suddenly spiking in 2050.

Yet the truth is just the opposite.

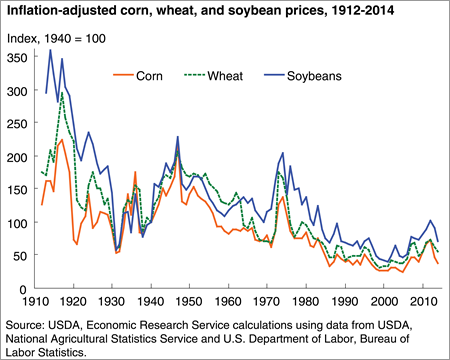

Graph 1 below shows trends in the international prices of corn, wheat, and soybeans over the past 100 years or so prepared by the US Department of Agriculture, on which price corrections have been made (even if we grant that the price of corn has risen by 1.5-fold, if general price levels double the real price of corn will have conversely fallen; price corrections refer to an attempt to view the real price by excluding factors like inflation and deflation). While we may observe some temporary pikes, it is obvious that these prices are trending downward. Over this same period, there has been a greater than four-fold increase in the population. Yet even though we can say there has been a population explosion, no chronic food crises have occurred.

Graph 1

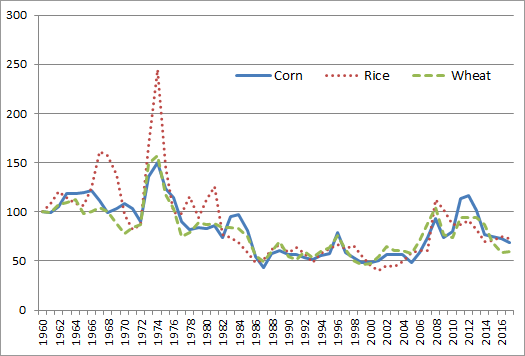

Next is Graph 2, which shows trends in the international prices of corn, rice, and wheat with the year 1960 taken as 100 (real prices on which price corrections have been made). In the 20-year period between about 1985 and 2005, price levels were roughly half what they were in 1960. Since then, they have only exceeded levels from 1960 in exceptional years. From this we can conclude that grain prices have remained stable at a low level over the long-term. This lacks even the faintest suggestion of the food crises which are claimed will occur over the long-term.

Graph 2

The population has increased 2.4-fold, grain production has increased 3.4-fold

The reason for this is simple: because increases in food supplies have surpassed the increased demand due to populations and income.

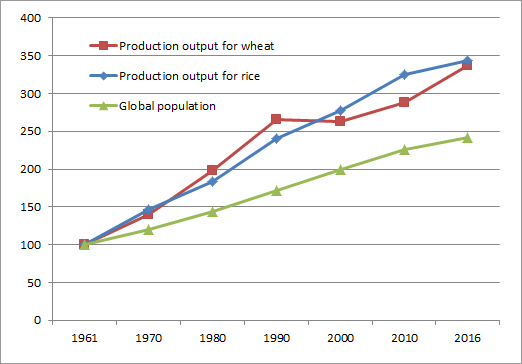

Next is Graph 3, which shows trends in the global population and in production output for rice and wheat, with the figures from 1961 taken as 100. The population has increased 2.4-fold, while grain production for both rice and wheat have increased by 3.4-fold. This increase in grain production is the reason for why grain prices have remained at low levels.

Graph 3

Those people fanning fears of a food crisis have asserted that no increases in the area of farmland can be expected worldwide, on top of which the increases in yields per unit of area have been slowing down. Therefore, we cannot count on any growth in global grain production gained by multiplying the yields per unit of area against the area of farmland.

Yet no such trends are to be found on the above graphs. If this were true, then this should already be reflected in the prices of grains, but it is not. Yet conversely, there is the possibility that ICT, AI, biotechnology, and other such advances will lead to increases in yields per unit of area over and above anything we have seen before.

In addition, there are some regions in the world where substantial increases in their area of farmland can be expected, such as Brazil. Whereas Japan only has 4.5 million hectares of farmland, Brazil is said to have about 100 million hectares of additionally usable farmland in its savanna regions which are called the Cerrado, and not Amazon regions alone.

Hiroyuki Kawashima, an Associate Professor at the University of Tokyo, expressed opinions to this effect in 2008. Back then I thought that it did not matter how much farmland the country had, because unless it was able to improve its infrastructure from said regions to its ports and other shipping facilities, then its supply of food would not increase. But in recent years Brazil has been rapidly improving its infrastructure.

The true intent behind the food crisis theory

Yet if the possibility of a food crisis occurring is so small, then why are the FAO, MAFF, and others fomenting fears that one will occur?

Farmers are the ones who benefit the most from a food crisis. During the era of postwar food shortages, during which some people starved to death, farmers profited handsomely by selling agricultural produce on the black market. People living in urban areas suffering from hunger would go out to the farmer's gates, where they would receive food in exchange for their precious clothing from farmers who had adopted a haughty and high-handed approach. The Japanese term takenoko seikatsu (a phrase that literally means "bamboo shoot life," but which refers to surviving by selling one's possessions) is derived from the fact that people would gradually sell off the clothes from their own dressers, thereby being stripped like a bamboo shoot of its skin. It was an extraordinary time in which agricultural produce commanded far greater purchasing power than the yen, which was dropping in value due to inflation.

The farmers prospered for a time, yet to this day, there are quite a few people who still hold a grudge against how the farmers responded back then. The bitter resentment at being preyed upon is not something that just goes away. By the way, back then there were no imports, so Japan's self-sufficiency rate for food, which MAFF officially tries to increase from current 38%, was 100%.

As will become apparent hereafter, responses to food crises and food security are inherently matters advocated for by consumers, not something that farmers or the agriculture industry advocate for. It is due to goals such as these that the duty to supply food in a stable manner is imposed upon farmers. It is possible that they could be compelled to undertake adverse dispositions of increasing production or delivering food to the government at a lower price than in the market, as was done during the post-war period.

The agriculture industry should be the one to suffer the most from detrimental treatment during a food crisis, yet they are among the loudest voices calling for responses to said crises. What could explain why such a curious phenomenon as this would occur?

The reason is simple. If not only the agriculture industry in Japan, but the worldwide agriculture industry, as represented by the FAO, raise a clamor about food crises, then they can expect budget increases for their organizations with the goal of protecting agriculture owing to the thinking that production should be increased.

This is not just a claim made by the agriculture industry in the form of international organizations, state organs like MAFF, research organizations like the agricultural departments at universities, and private agricultural organizations. Agricultural economists and self-proclaimed experts on agriculture and food issues have also collectively raised the alarms about food crises, with the mass media jumping on the bandwagon as well. Articles saying that no food crises will occur are not popular, but the ones saying that such a crisis will occur are. The ordinary person, who lacks evidence that would dispel their concerns and allow them to make a decision on the veracity of these claims, is left with no choice but to believe these so-called "experts."

This is how the theory of the 2050 food crisis was cooked up by them.

Either way, no food crises will occur in Japan

Yet even in the unlikely event that a global food crisis occurs and grain prices soar as the agriculture industry is claiming, no food crises would occur in Japan.

Back in 2008 worldwide grain prices shot up by three to four-fold, and many people in developing countries had to wait in long lines for food rations. Yet in this same year Japan's consumer price index for food only rose by 2.6%. This is because the share accounted for by agricultural and marine products of final consumption for food and beverages is 15%, of which imported agricultural and marine products (which include grains) only account for 2%.

It is surely the case that no Japanese people suffered from food crises at this time. Therefore, even if a food crisis occurs from soaring grain prices that hits countries like the Philippines, Japan, as a country with high-income levels and strong economic clout, will be able to continue importing food without feeling the pain from this. You may catch sight of reports saying that Japan unsuccessfully purchase this or that on the international market. Yet even if cases arose in which Japan was unable to purchase certain, specialty high-end products, so long as Japan's economic clout remains largely intact it will not suffer from a situation in which it is no longer able to purchase commodities such as grains.

For a food crisis to occur in Japan, it would have to involve the disruption of sea lanes due to military conflict or the like, thus preventing foreign ships from approaching Japan out of fear. It would be a case of Japan's physical access to food being cut off, rather than its economic (monetary) access, just like when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred.

(This article was translated from the Japanese transcript of Dr. Yamashita's column in "Webronza" on July 9, 2018.)