Media Global Economy 2014.09.19

The Agriculture in the TPP Negotiations

The US has advocated that Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) should be the free trade agreement in the 21st century. It has claimed that all tariffs on goods be eliminated and that new rules and disciplines should be established on such areas as trade and environment, trade and labor, state-owned enterprises, investment, and government procurement which are not at all or insufficiently covered by WTO.

Most of the participants in the TPP negotiations went on the principle that all of the tariffs on the agricultural products be eliminated. Whenever there is a principle, however, there is an exception in real life. The US has tried to maintain its tariffs on sugar imported from Australia and tariffs on dairy products imported from New Zealand. Canada would like to maintain its tariffs on dairy and poultry products, while the US demands Canada to eliminate tariffs on dairy products.

No other country, however, is seeking as many TPP exemptions as Japan, which joined the negotiations in 2013. The Japanese Diet agricultural committees have adopted resolutions urging the government to have Japan's rice, wheat, beef and pork, dairy products and sugar exempted from tariff elimination under the TPP agreement and to leave the negotiating table if unable to do so. These resolutions constrain and restrict the Japanese government's TPP negotiation.

Intensive negotiations were held between Japan and the US during President Obama's state visit to Japan in last April. According to Japanese media sources, the possible results of the negotiations seem to be: tariffs on Japan's "five priority items" of agricultural products will not be eliminated; among these five items the current tariff rates will be maintained for rice, wheat and sugar; the import quota will be expanded for American rice and wheat; and tariff rates will be reduced on beef, pork and dairy products. However, the size of the reduction is yet to be agreed.

Why has the US agreed to the maintenance of tariffs on rice, wheat and sugar? First of all, American sugar is not competitive. Secondly, the US negotiators well understand the political significance of rice in Japan and the difficulty of reducing tariffs on rice. Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries as a state trade enterprise has imported wheat under a fixed ratio of 60% from the US, 20% from Canada and 20% from Australia for the past several decades. It is like a managed trade. If the tariff on wheat is to be eliminated, American wheat will have to face competition not only from Canada and Australia but also from the EU. This may damage US wheat exports. From this perspective, maintaining the tariff on wheat and expanding the quota could be beneficial to the US.

As regards beef and pork, the US demands significant reduction of tariffs on beef and pork. Though the Japanese beef and pork industries are strongly opposed to such a reduction, they will not suffer serious damage due to a lack of tariffs.

The tariff on beef has been reduced from 70% in 1991 to the current rate of 38.5% - nearly half. Nonetheless, production of wagyu (Japanese cattle) beef, which occupies the biggest share of beef production in Japan, has increased in this period. In addition, due to exchange rate fluctuations, the Japanese yen has depreciated by about 35% since 2012. In 2012 beef priced 100 yen was imported with tariff of 38.5 yen, which makes the import price 138.5 yen. Currently, the same beef is priced 135 yen due to yen depreciation before tariff is imposed. This price is nearly the same as the import price after customs clearance in 2012.

Beef produced from male calves born from cows fed by dairy farmers and culled milk cows may be affected by the competition with imported beef. However, beef other than wagyu amounts to about a ninth of the total beef production of 460 billion. If farmers producing these other types of beef suffer we may support them by a direct subsidy from a government fund. Even if the amount of subsidy may be a third of the total production, it amounts to merely 15 billion yen.

Special arrangements are made for pork imports, by which importers should pay the difference between 410 yen per kilogram and the actual import price as an import duty. This means that an import price of pork is always raised to 410 yen if it is imported at a price less than that. In practice, importers prepare a package of pork meat which consists of high-class meat, such as loins and tenderloins, and low-class meat to be used for hams or sausages so that a price of the package is set near around 410 yen per kilogram. Therefore, the amount of import duty actually paid is very small. Although the total amount of imported pork reached 400 billion yen in 2010, it is reported that the import duty actually paid only amounted to 18 billion yen which was about 4.5% of total imports.

The above Japanese media report on the bilateral negotiation between Japan and the US aroused a strong opposition to the US Trade Representative by the US agricultural industry. It demands the USTR to eliminate the Japanese tariffs on those products, beef and pork in particular. 140 US congressmen sent a letter to President Obama on July 30 that the US should conclude the negotiations without Japan since Japan had made an unprecedented and objectionable offer exempting numerous products from tariff elimination, which could set a damaging precedent for other trade talks.

A Japanese politician mentioned that Japan and the US fought hard for their respective national interests in the negotiations. It is understandable that the national interests of the US are to expand exports for the benefit of their domestic industry. What are the national interests of Japan? Does the Japanese government negotiate to protect the domestic agricultural industry? If it aims to protect Japan's agriculture, it does not need to defend tariffs; its goal can be achieved by direct payments out of a government fund as the US and the EU do.

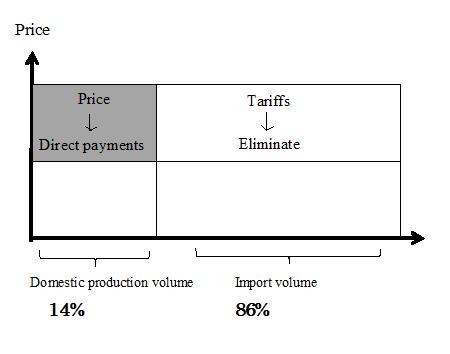

What those tariffs are really protecting are high domestic prices for agricultural products--in other words, food prices. For example, to protect the high price of domestically-produced wheat, which accounts for only 14 percent of total consumption, tariffs are levied on the foreign wheat that accounts for the other 86 percent, forcing expensive bread and noodles upon consumers. Just covering the difference between domestic agricultural product prices and international prices with direct payments would benefit consumers hugely by removing the consumer burden for not only domestic produce but also foreign farm products.

Figure1: The reduction of the consumer burden by the shift from price support to direct payment

In the case of rice, the government has used some 400 billion yen of taxpayers' money to have farmers reduce the acreage used for rice cultivation. As a result, supply has been reduced and prices boosted for the Japanese diet staple of rice, on top of which consumers have paid out over 600 billion yen. The total public burden entailed in producing 1.8 trillion yen's worth of rice is more than one trillion yen. High rice prices too are protected by tariffs. Many politicians opposed the consumption tax hike on the grounds that it would make food more expensive for poor people--yet bolstering food prices with tariffs and reduced rice acreage is apparently for the national good. To the extent that Japan maintains its policy of protecting farmers with domestic prices that are more expensive than international prices, tariffs will be required.

The national interests that the Japanese government are trying to defend by tariffs is not agriculture but the high price of agricultural products (and therefore high price of food). In order to maintain high prices tariffs are necessary and to protect the existing tariff rates the Japanese government needs to accommodate the demands of US industries for an expansion of import quota (with no duty) on rice and wheat. With this measure, imports will increase and food self-sufficiency which the Japanese government has advocated to increase will decrease.

Even if we protect the domestic market from foreign agricultural produce using tariffs, the graying of society and population decline will see that market shrink. To sustain and boost agriculture, we need to create export markets. If we abandon the rice acreage reduction policy and bring the domestic rice price down, farmers will start to export. However, no matter how hard farmers work to cut costs, they won't be able to export if our trading partners have in place high tariffs or non-tariff barriers such as SPS measures and state-owned enterprises which charge great mark-ups. If Japan is not going to participate proactively in trade liberalization negotiations like the TPP that do away with trading partners' trade barriers, Japanese agriculture will simply proceed with its assisted suicide.

When agriculture could be protected with direct payments, why does maintaining agricultural tariffs, as well as the high price of agricultural products protected by those tariffs, translate into the national interest?

The answer is an entity which exists in Japan but not in the US or the EU--the strongest interest group in Japanese politics, Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, or JA.

Agricultural cooperatives in the US and the EU specialize in one or some of the activities such as sales, material purchases or other aspects related to a particular agricultural product or product group, or providing financial service to farmers. Japan's JA has a hand in everything from banking, life insurance and accident insurance for farmers and non-farmers alike to sales of all agricultural products and materials, as well as the supply of daily commodities and services including gas station, wedding and funeral services. There is no other corporate body or legal person in Japan that can match it. Banks are prohibited from engaging in other business, and life insurance companies can't handle accident insurance and vice versa.

Until 1995, the government supported farmers' income by setting a high price on the rice which the government bought from farmers via JA. Even after that system ended, rice prices have been kept high through the rice acreage reduction policy.

Thanks to high rice prices, numerous inefficient part-time micro-farmers with high production costs have remained in the rice industry. As a result, farmland has not accumulated in the hands of full-time farmers, so it has been difficult for them to expand the scale of their operations to bring down costs and boost profits. The high price of rice has also reduced rice consumption. With both production and consumption impacted by the high rice price, the rice industry has declined.

Lifting the price of rice proportionally increases JA's revenue from rice sales. For JA, the continued presence of the very part-time rice farmers who are pushing rice farming into decline has actually been advantageous. Income from part-time work, which is four times greater than farming income, as well as profits from the sale of farm land for other purposes (trillions of yen every year), is all deposited in the accounts of JA, which is permitted to engage in banking, building JA into Japan's second-biggest mega-bank. Keeping rice prices high and part-time farmers on their farms has been the foundation of JA growth.

Even if tariffs were eliminated and prices fell, if we used government funds to cover the price fall, farmers would not be affected. If tax-payers were not prepared to provide income compensation for part-time farmers with high incomes and only full-time farmers received compensation, lower rice prices would encourage part-time farmers to part with their land.

However, while farmers would not be affected, JA would suffer from reduced sales commission revenue as a result of the lower prices. Furthermore, if lower prices bring about the exit of part-time farmers, JA would be shaken down to its organizational foundations. JA has launched a fierce TPP opposition movement. The heart of the problem is not the TPP and agriculture--it's the TPP and JA.

Japanese agriculture could survive by exporting highly value-added agricultural products such as Koshihikari, a Japanese high-quality variety of rice while importing rice from Vietnam. Japan, however, is reluctant to opening its agricultural market for TPP participants including developing countries. It deprives them of opportunities to export agricultural products to Japan.

In addition, the Japanese insistence on seeking many exemptions from tariff elimination would help other countries claim exemptions from other fields of TPP negotiations such as rules and disciplines on state-owned enterprises. This might not only reduce or diminish the level of ambitions of TPP agreements which might make a great deal of contributions to the World's trade system but hinder those countries, developing countries in particular, from making structural reform of their economy through participating TPP.