Media Global Economy 2014.04.15

The Error of Anti-TPP Arguments

Agriculture will not be destroyed even if tariffs are removed

While Japan levies no tariffs at all on some agricultural products such as flowers and cotton, others such as rice and konnyaku attract steep tariffs of over 200 percent. More specifically, no tariffs are levied on 24 percent of all agricultural items (or tariff lines), and tariffs of more than zero percent but less than 20 percent are levied on 48 percent of agricultural items, bringing the total ratio of items on which tariffs of less than 20 percent are levied to 72 percent. By contrast, the ratio of agricultural items on which tariffs of more than 200 percent are levied is around eight percent. In other words, most agricultural items attract no or extremely low tariffs when they are imported into Japan.

Of Japan's gross agricultural production in FY2010, the percentage of gross agricultural production which is protected by little or no tariffs is at least 50 percent: 28 percent for vegetables, nine percent for fruit, nine percent for poultry, and four percent for flowers. Some pundits are arguing that if Japan participates in the TPP and eliminates tariffs, Japanese agriculture will be destroyed, but this is not correct.

The current tariff system emerged as a result of the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations which were concluded in 1993. At the time, Japan's agricultural product imports comprised two categories: items which could be imported freely to the extent that a tariff was paid; and those subject to quantitative restrictions, whereby a ceiling was placed on import volume. In neither case were tariffs particularly high.

At the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations, it was agreed to prohibit quantitative restrictions and utilize only tariff-based import systems. In exchange for eliminating quantitative restrictions, countries were allowed to levy tariffs on the difference between the domestic price and the international price (market price differential, or MPD) only for those products on which quantitative restrictions had previously been placed. This was called "tariffication".

To protect domestic agriculture, these tariffs covering the international price differential were set as high as possible by using comparatively cheap international prices. In the case of rice, what was used was not the price of short-grain rice like Japanese rice, but rather of long-grain Thai rice. Thus, a tariff of 402 yen per kilogram was set. The current tariff has been reduced 15 percent down to 341 yen in line with the Uruguay Round agreements, which is still well above the domestic price of 230 yen. Even if, for example, the price of imported rice was zero, once the tariff was paid it would still be impossible to compete with domestic rice. This is an excessively protective tariff.

Does Japan have a low level of agricultural protection?

Agricultural economists who emphasize agricultural protection are strangely insistent that Japan has limited agricultural protection. If protection is limited, it would surely be no problem to eliminate tariffs, and the amount needed if government funds were used instead to protect farmers would also be limited. However, there is a parallel and contradictory argument that tariffs are necessary and that the fiscal burden after tariff elimination would be huge.

Another argument is that the fiscal burden as a ratio of agricultural production is 65 percent in the US but only 25 percent in the case of Japan, which is taken as proof that Japan's agricultural protection is low.

However, first of all, these arguments ignore the characteristics of Japan's method of protecting agriculture, which is not to provide subsidies out of government funds but rather to set high prices underpinned by tariffs. In other words, they are trying to compare the relative extent of protection based on fiscal spending alone, when fiscal spending plays only a small role in Japan's protection.

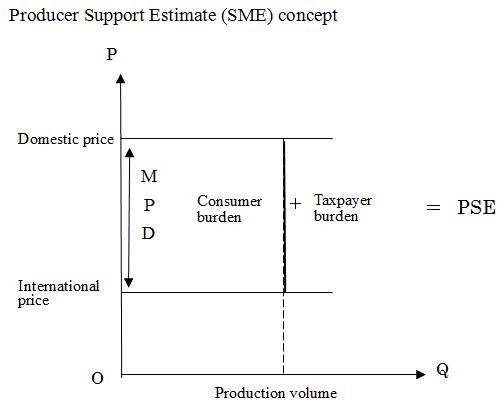

The OECD-developed agricultural protection index Producer Support Estimate (PSE) comprises two components: the taxpayer burden, whereby farmer income is maintained through fiscal spending, and the consumer burden, which is equivalent to the amount of production volume multiplied by the difference between domestic and international prices, and is the amount of income transferred to farmers as a result of consumers paying farmers not the cheap international price but rather the expensive domestic price.

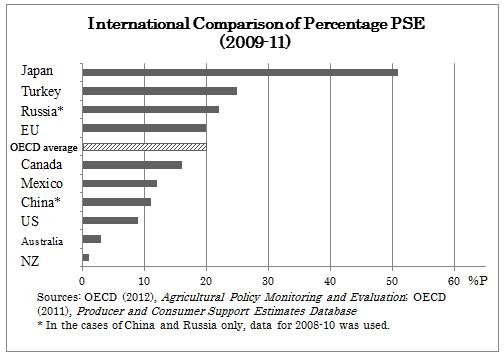

According to the OECD, the ratio of the PSE, or agricultural protection, to total farm receipts (percentage PSE) as at 2011 was 7.7 percent in the US and 17.5 percent in the EU, but an extraordinarily high 51.6 percent in Japan. Further, compared to 1999 when all countries had high levels of protection, in recent years, both the US and the EU have shrunk that percentage markedly-from 25.5 percent down to a third of that level in the US, and from 38.2 percent down to half that level in the EU. Japan, by contrast, has only seen a slight reduction from the 1999 level of 59.9 percent.

Looking at PSE breakdowns in the different countries, where the consumer burden ratio in 1986-88, the base period used in the Uruguay Round negotiations, was 37 percent for the US, 86 percent for the EU and 90 percent for Japan, in 2010 those percentages had become six percent for the US, 15 percent for the EU and 78 percent for Japan (around 3.6 trillion yen). Despite the US and the EU shifting from price support to direct payments using government funds, Japan's agricultural protection remains focused on price support. To ensure that domestic prices are well above international prices, tariffs need to be high. You can see how invalid it is to compare the extent of protection on the basis of fiscal spending alone.

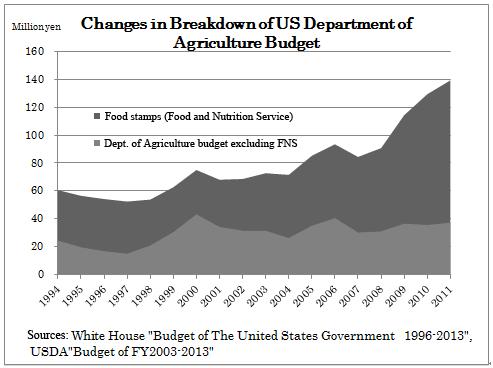

Second, Japan even has a higher rate of fiscal spending. The argument that Japan has less agricultural protection than the US is based on the idea that the US Department of Agriculture devotes its entire budget to agriculture. However, the budget for food stamps for low income earners has traditionally absorbed half of the Department of Agriculture's budget. In recent years, the relaxation of eligibility criteria has seen the food stamp budget triple in the space of a decade, and now some 70 percent of the Department of Agriculture's budget goes in that direction. In 2011, the Department's total budget was US$139.4 billion, of which US$102.2 billion went on food stamps, while only US$37.2 billion was spent on agriculture. There is no comparing Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) budget, almost all of which goes on agriculture, and that of the US. The agriculture budget of the US is only a tenth of production, where in Japan it is one quarter. Moreover, the reason that food stamps are included in the Department of Agriculture's budget is to garner support for agricultural protection from consumers and urban voters.

Some agricultural economists also argue that a low food self-sufficiency ratio is proof of openness. However, if domestic produce has no price competitiveness even given the same tariff, imports will increase and the self-sufficiency ratio fall. Food self-sufficiency is different from market openness and low tariffs. If Japan's tariffs were at the same level of those of the US, our food self-sufficiency ratio would fall even further. The US exports cereals while Japan imports them, and yet Japan has higher cereal tariffs. According to the WTO, the average tariff rate for cereals and preparations is 3.7 percent in the US and 76.6 percent in Japan. Can we really call Japan--the importing country--more open?

Food industry burdened by distorted agricultural administration

Where approximately 30 percent of the food that consumers currently buy is from restaurants and 50 percent processed food products, fresh food is down to only 20 percent. Until 20 years ago, agriculture and fisheries accounted for 22 percent of the GDP of food-related industries but this has now dropped to 12 percent (2009). In 2009, the percentage distribution for food-related industries was 39 percent processing industries, 26 percent distribution, 22 percent restaurants, and 12 percent agriculture and fisheries.

In other words, rather than directly consuming agricultural products, the Japanese people are now consuming foods that the food processing and restaurant industries have processed and prepared. Rice is the same. The amount eaten at home is now rivalled by the amount eaten in restaurant meals and convenience food. From the agricultural side, 32 percent of domestic farm and fisheries products are going to final consumers (fresh food), 63 percent to the food processing industry and seven percent to the restaurant industry (2005). This makes the food processing and restaurant industries important customers for agricultural produce.

However, because agriculture continues to emphasize fresh products in its sales strategy, it is losing the capacity to supply agricultural produce that meets the needs of the food processing and restaurant industries in terms of price and quality. MAFF too has kept tariffs high for agricultural produce as fresh food, while blithely slashing tariffs for confectionery and other processed foods.

Confectionery manufacturers and other makers of finished products have low tariffs placed on their products, but all their raw materials--rice, wheat, sugar, starch and dairy products--are protected with high tariffs. Even if imported agricultural products are used as raw materials, the high tariffs levied on them still make raw materials expensive. This places domestic manufacturers at a huge competitive disadvantage against products from overseas which face only low tariffs. Domestic manufacturers are left with no choice but to go offshore for their raw materials and process them there, exporting the finished products back to Japan. As a result, Japanese agriculture has lost an important customer for its own products.

The root of the problem lies with the agricultural administration that has protected agriculture with high tariffs. If our means of agricultural protection was shifted from price support and tariffs to direct payments from government funds, the problem would be resolved and demand for domestic agricultural produce too would grow.