Media Global Economy 2014.04.01

The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement and Revitalizing Agriculture

The Diet agricultural committees have adopted resolutions urging the government to have Japan's rice, wheat, beef and pork, dairy products and sugar exempted from tariff elimination under the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement and to leave the negotiating table if unable to do so. Diet members apparently equate the national interest with maintaining tariffs.

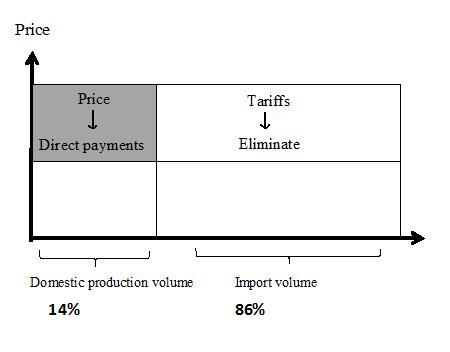

However, what those tariffs are really protecting are high domestic prices for agricultural products-in other words, food prices. For example, to protect the high price of domestically-produced wheat, which accounts for only 14 percent of total consumption, tariffs are levied on the foreign wheat that accounts for the other 86 percent, forcing expensive bread and udon noodles upon consumers.

In the case of rice, the government has used some 500 billion yen of taxpayers' money to have farmers reduce the acreage used for rice cultivation. As a result, supply has been reduced and prices boosted for the Japanese diet staple of rice, on top of which consumers have paid out over 500 billion yen. The total public burden entailed in producing 1.8 trillion yen's worth of rice is more than one trillion yen. High rice prices too are being protected by tariffs. Many politicians opposed the consumption tax hike on the grounds that it would make food more expensive for poor people--yet bolstering food prices with tariffs and reduced rice acreage is apparently for the national good.

To the extent that Japan maintains its policy of protecting farmers with domestic prices that are more expensive than international prices, tariffs will be required. No other country is seeking as many TPP exemptions as Japan. At the end of the day, the Japanese government will probably negotiate to keep rice at least off the table.

The underlying assumption is that Japanese agriculture's small scale makes it unable to compete with US and Australian agriculture. In terms of the amount of land operated per farm, if we put Japan at 1, the EU would be 6, the US 75 and Australia 1,309. Other things being equal, the greater the scale, the lower the cost. However, scale is not the only important factor. While the US is the world's largest exporter of agricultural produce, its farmland is only one-seventeenth the size of Australia's. Crop types and crop yield per unit area of land cultivation both differ according to soil fertility. Barren soil means that most of Australia's agriculture comprises cattle-grazing on plains, whereas corn, soybean and wheat production dominates in the US.

In addition, in agricultural produce as in cars, there are major quality differences. In Hong Kong, Koshihikari rice produced in Japan fetches a price 1.6 times higher than Koshihikari grown in California, and 2.5 times higher than Chinese Koshihikari.

Moreover, the argument that Japanese agriculture cannot compete with the US and other countries assumes that the elimination of tariffs is accompanied by no other government action. The agricultural scale of the EU might be 10 percent that of the US and 0.5 percent that of Australia, yet thanks to high productivity and direct government payments, the EU can export grain. The wheat yield of the United Kingdom is five times higher than in Australia.

The United States and the European Union have shifted to a policy of protecting agriculture not with high prices but with direct payments out of government coffers. Even if removing tariffs in Japan brought down food prices, we could avoid impacting farmers by following the US and the EU in using government funds to cover the difference between domestic and international prices, and consumers would benefit. The agricultural sector argues that the great disparity between domestic and foreign prices would require massive government spending, but this is tantamount to admitting that a huge burden is currently being imposed on consumers. As in the above case of wheat, consumers are also paying high prices for imported foreign wheat, so the consumer burden is even larger again. Just covering the difference between domestic agricultural product prices and international prices with direct payments would benefit consumers hugely by removing the consumer burden for not only domestic produce but also foreign farm products.

In fact, the difference in price between Japanese rice and that produced in China and California has shrunk to around 30 percent. Because the price differential between Japan and other countries is shrinking, contrary to the argument of the Japanese agricultural sector, only relatively minor direct payments would need to be made.

By shrinking production and pushing up prices, the rice acreage reduction policy has robbed Japanese rice of its competitiveness. The per-unit quantity cost is calculated by dividing cost per unit of land by crop yield, so if the yield rises, the cost goes down. However, since the government brought in its rice acreage reduction policy to constrain production, selective breeding programs designed to boost crop yield have been given up. Currently, Japan's average crop yield is 40 percent less than California's. In addition, because rice prices are high, even micro-farmers with high costs have kept farming. Consequently, farmers whose main source of income comes from farming haven't been able to amalgamate enough land to expand their scale of production.

If we dropped our rice acreage reduction policy and rice prices went down accordingly, micro-farmers would lease out their land. Making direct payments only to full-time farmers would boost their capacity to pay land rents and farmland would concentrate in their hands. The rice production cost for farms of 15 or more hectares is 6,378 yen per 60 kilograms. If abandoning our rice acreage reduction policy brought Japanese rice yields up to Californian levels, the production cost would drop by 29 percent to 4,556. That would be less than half the national average of 9,478 yen.

Some media outlets incorrectly reported that the rice acreage reduction policy would be abolished under the current review. If this were the case, Japan could have taken more flexible position in TPP negotiations. No one in the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has stated this. The Prime Minister Abe said so in the beginning but he denied in the Diet budgetary committee what he said.

The rice acreage reduction policy has been in place since 1970, and is essentially a subsidy to be paid to rice farmers who convert paddies to other crops in order to reduce rice production. The amount of subsidy is calculated on the basis of the size of area to which rice production is converted to other crops. In addition to this subsidy, in 2010, the then-ruling party, the Democratic Party of Japan, introduced a new subsidy called individual household income support to be paid to rice farmers who comply with a target production quantity which sets a maximum limit of rice production. This subsidy is paid on the basis of the size of area in which rice is actually planted. This current review concerns the latter subsidy, and is intended to abolish it as well as the target production quantity.

The funds obtained by the abolishment will be utilized to expand the set-aside subsidy for the conversion to rice for rice flour or feedstuff. If this current review is effective, it could result in a reduction of the planting of rice for direct human consumption and a further increase of the price of rice. It would also entail much greater expense upon government than MAFF anticipated due to a great price gap between rice for direct human consumption and rice for rice flour or feedstuff.

The second problem of the planned change is that it will cause a serious trade dispute. If the production of rice for feedstuff and rice flour increases, corn and wheat imports from the US could also fall substancially. It is possible that the US would bring the case to the WTO, and consequently be possible that the US be allowed to take retaliatory measures by imposing higher import duties on imports of Japanese cars for example. This could have a significant impact on the Japanese economy.

The financial burden and trade dispute with the US by export subsidies led to the fundamental policy reform in the EU in 1993. The current review of the rice acreage reduction policy may lead to its abolishment.

Even if we protect the domestic market from foreign agricultural produce using steep tariffs, the graying of society and population decline will see that market shrink. To sustain and boost agriculture, we need to create export markets. However, no matter how hard farmers work to cut costs, they won't be able to export if our trading partners have in place high tariffs or non-tariff barriers such as SPS measures and state-owned enterprises which charge great mark-ups. If Japan is not going to participate proactively in trade liberalization negotiations like the TPP that do away with trading partners' trade barriers, Japanese agriculture will simply proceed with its assisted suicide.

If we abandon the rice acreage reduction policy and bring the domestic rice price down to 8,000 yen, and if the Chinese rice price rises to 13,000 yen in response to higher labor costs in the Chinese rural sector and yuan appreciation, farmers will export, in turn lifting the domestic price. Production will expand. Given the world-leading quality of our rice, boosting productivity and introducing direct payments to achieve price competitiveness would grant us a decisive advantage.